How Indian Films Are Shaping Politics of Exclusion

Image Courtesy: Twitter/@MovieReviewsBlg

Storytelling has always been a fundamental force in shaping societies, influencing how people perceive history, identity, and belonging. From ancient epics to modern cinema, narratives have the power to build inclusive communities or entrench divisions, to challenge oppression or justify it.

Films, as one of the most accessible and influential forms of storytelling, do not merely entertain; they construct collective memory, dictate cultural norms, and shape public consciousness.

In democratic societies, cinema can be a tool for critical thought, empathy, and resistance. However, when controlled by dominant ideologies, it can become a vehicle for propaganda, erasure, and exclusion.

Today, Indian cinema is at crossroads, once a space for pluralistic storytelling, it is now increasingly co-opted to serve majoritarian narratives. By selectively glorifying certain histories, vilifying communities, and suppressing dissenting voices, cinema is being transformed from a medium of artistic expression into an instrument of ideological conformity. This growing capture of film by majoritarian politics demands urgent scrutiny, as it threatens not only artistic freedom but also the foundations of a diverse and democratic society.

Cinema, a powerful medium of storytelling, has historically played a crucial role in shaping cultural narratives and national identities. However, in recent years, Indian cinema has increasingly become a tool for majoritarianism; promoting a singular, often exclusionary perspective that marginalises minority voices and reinforces the dominance of a particular cultural and religious identity. From historical epics to contemporary nationalist dramas, the film industry is subtly, and sometimes overtly, propagating majoritarian politics, serving the interests of the ruling ideology.

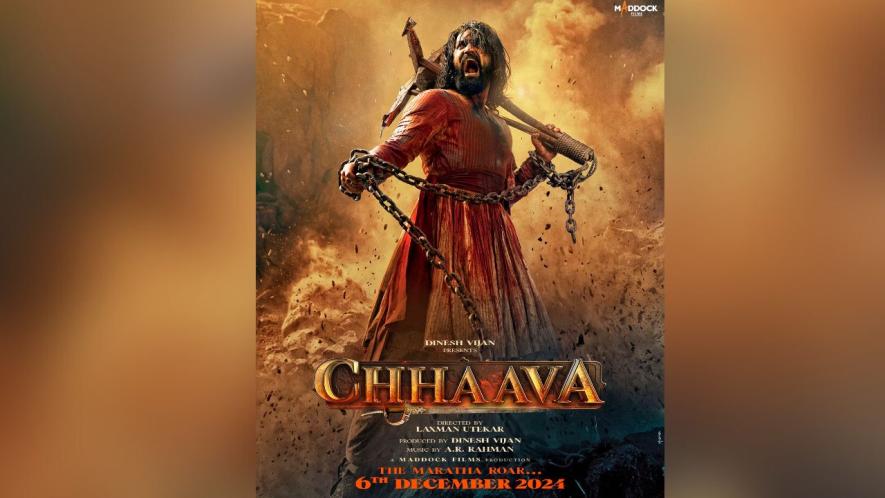

This phenomenon is not accidental; cinema has traditionally been known to mirror the society, it is a carefully orchestrated effort that aligns with the political climate, using cinematic storytelling to rewrite history, demonise certain communities, and glorify majoritarian heroes. A recent example of this trend is the film Chhava, which, like many others before it, exemplifies how the industry is being used to push a one-dimensional narrative that sidelines historical complexity in favour of a dominant ideology.

Cinema as a Tool of Majoritarian Politics

However, cinema has evolved beyond merely reflecting society; in contemporary India, it is increasingly being used as a tool to manufacture consent. Over the past decade, the rise of Hindutva politics has reshaped cinematic narratives, stories that once embraced diversity and social justice are now being leveraged to reinforce cultural hegemony.

Many recent films have engaged in historical revisionism, presenting distorted versions of history that align with the current political idea of nationalism. These films selectively emphasise the heroism of Hindu rulers while portraying Muslim rulers and other communities as tyrannical, oppressive, or inferior.

Chhava, a film based on Sambhaji Maharaj, exemplifies this pattern. While the Maratha legacy is undoubtedly significant, the film’s selective portrayal of historical characters raises concerns about its agenda. The erasure or vilification of Soyarabai Bhosale and the controversy around historical accuracy reflect an effort to sanitise history to fit the contemporary majoritarian narrative.

The growing influence of majoritarian politics in cinema is evident in the glorification of a Hindu nationalist identity as the central pillar of Indian culture. This is achieved by, promoting films that celebrate Hindutva-aligned historical figures while ignoring or distorting the contributions of other communities, projecting a homogenised Hindu identity, sidelining the internal diversity of Hinduism itself, as well as the pluralistic traditions that have defined India for centuries.

Reinforcing hyper-nationalist rhetoric, wherein the protagonist embodies an unquestionable loyalty to the state, often portrayed as synonymous with Hindu majoritarian values. Films such as The Kashmir Files (2022) and Gadar 2 (2023) have amplified this narrative, weaponising history and patriotism to construct a divisive political discourse.

The increasing dominance of majoritarian narratives in cinema leaves little space for dissent or alternative viewpoints. The representation of Muslims, Dalits, and other marginalised communities in Bollywood has become more stereotypical and exclusionary, Muslim characters are often reduced to either villains, terrorists, or regressive patriarchs, reinforcing Islamophobic stereotypes.

Films like Article 15 (2019), are now largely absent from mainstream narratives. Alternative histories and perspectives such as the role of Bahujans in medieval resistance movements are ignored in favour of a dominant Brahminical-Maratha nationalist lens. The backlash against scholars and activists questioning these portrayals further demonstrates how cinema is being weaponised to control historical discourse and suppress alternative narratives.

The Role of the Censor Board

The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) has increasingly become an ideological gatekeeper rather than an impartial regulatory body. It is not just restricting films for explicit content but actively shaping political narratives by selectively approving, censoring, or delaying films based on their ideological alignment. The CBFC’s decisions in recent years indicate a clear bias towards majoritarian narratives, while films that critique dominant power structures often face unjustified cuts, disclaimers, or outright bans. Films like The Kashmir Files (2022), which promotes a sectarian narrative, were cleared without any significant cuts, despite concerns over its divisive content and communal portrayal.

On the other hand, films like Padmaavat (2018) and Lipstick Under My Burkha (2016) faced extreme scrutiny, protests, and delays, either for questioning dominant gender norms or for not fitting into the Hindutva cultural framework. Most importantly, films like An Insignificant Man (2017), which documented the rise of the Aam Aadmi Party, and India’s Daughter (2015), which addressed gender violence, were either banned outright or severely restricted, revealing the Board’s involvement in controlling political narratives. The selective nature of censorship silences critical voices, gate-keeps historical narratives, and imposes ideological filters that favour the state’s dominant agenda.

Reclaiming Cinema from Majoritarian Influence

Cinema is not just a medium of entertainment; it is a powerful tool that shapes collective memory, cultural identity, and public consciousness. When it is monopolised by majoritarian narratives, it ceases to reflect the diverse realities of a pluralistic society and instead becomes an instrument of ideological dominance.

The increasing glorification of a singular national identity, historical revisionism, and the exclusion of marginalised voices threaten the very essence of democratic storytelling. This manipulation of cinema does not just distort history but also normalises sectarian divisions, erases dissent, and reinforces systemic biases. If we fail to challenge this growing influence, we risk allowing films to serve as state propaganda rather than platforms for artistic expression and social critique.

Reclaiming cinema means ensuring space for multiple perspectives, encouraging historical accuracy, and protecting creative freedom from the pressures of censorship and political interference. Only then can cinema truly serve as a mirror to society rather than a tool for cultural hegemony.

To counter the ideological capture of cinema, we must take active steps to resist the cultural hegemony being imposed through films. Encouraging and promoting independent films that challenge dominant narratives is essential. Rather than passively consuming cinema, audiences must engage critically with the perspectives films promote. Recognising subtle ideological biases can help prevent majoritarian narratives from being normalised.

A pluralistic film industry must provide space for multiple histories and identities, rather than enforcing a single dominant narrative. More representation from marginalised communities can counter the majoritarian stranglehold over storytelling. Filmmakers must be questioned for historical inaccuracies and ideological distortions, especially when they contribute to communal polarisation. Additionally, the CBFC must be reformed to function as a neutral certifying body, rather than a political instrument that shapes narratives to serve majoritarian interests.

Conclusion

If we are serious about resisting the majoritarian capture of cinema, we cannot ignore the role of the film industry and the Censor Board in filtering narratives to align with state ideology. Reforming the CBFC and diversifying cinematic storytelling is essential to ensure that Indian cinema remains a space for inclusive, critical, and diverse storytelling.

Cinema must not be reduced to a mouthpiece for majoritarianism. It should remain a platform for storytelling that embraces complexity, dissent, and the rich plurality of India’s past and present. If we fail to reclaim this space, we risk allowing an exclusionary, homogenised vision of history and culture to define the future of Indian cinema—and, by extension, Indian society itself.

Shirin Akhter is Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Zakir Husain Delhi College, University of Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.