Decoding Brahminical-Gene Through Popular Films

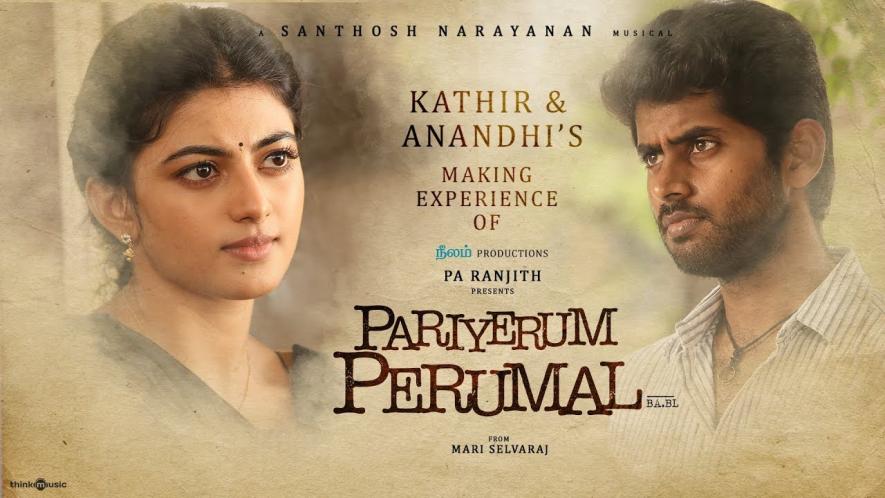

Image Courtesy: YouTube

After centuries of domination, surprisingly it is the ‘Brahminical-Gene’ which is under all sorts of threats. Now, the threat has manifested through Anuradha Tiwari’s assertion of her upper-caste identity. She is a professional who is against caste-based reservations and favours ‘merit’. As if ‘merit’ is devoid of any connections with caste.

A cursory look at the book Caste of Merit: Engineering Education in India, by Ajantha Subramanian, may help us understand how conditions that reproduce merit are shaped by caste. But being critical of oppression is not expected from someone who is trying to portray Brahmins as oppressed. Recently, Tiwari flaunted images of Brahmin-Gene-stickers as signs of wisdom, strength and pride—seeking Brahminical solidarity.

After hoarding a huge share of social advantages, the Brahminical-Gene is still so insecure. Even after sharing a miniscule percentage of high-stake jobs, the Brahminical-Gene needs to reassert its identity to secure jobs. Even after maintaining a complete monopoly over knowledge in the pre-colonial era, the Brahminical-Gene calls for a ‘fight-back’. And even after living out of other people’s alms and services for centuries—the privileged Brahminical-Gene is suspecting some disadvantage, because of what the caste census may reveal: the disproportionate nature power and privilege.

Why is the Brahminical-Gene so obsessed with ‘quota-people’? Why do they think that these underserving ‘quota-people’ have been snatching all their jobs and seats since the past seven decades? Can we even compare 70 years of affirmation against hundreds of years of hoarding resources and privileges?

A simple fact-check should be sufficient to shut the flawed upper caste phobia regarding ‘undeserving’ candidates getting everything on a platter while the general candidates ‘work harder’, yet fail to make the cut because of ‘quota’. Such an upper caste mentality seems to have forgotten the dismal number of government jobs and reserved seats that come under the ambit of reservation, if compared with the magnitude of private jobs along with the ocean of unorganised sector that constitutes over 95% of employment opportunities and remains outside the range of reservation. But the Brahminical-Gene loves to remain indifferent to such basic facts.

There is no other social institution that is so vehemently against the modern egalitarian agenda as much as the Brahminical caste system. It legitimised social inequality through ascriptive roles, endogamy, and everyday mutual repulsion. As an utterly oppressive system, it is heavily prejudiced in favour of those who belong to the upper and middle layers of the hierarchy, and invariably those who traditionally own land and other resources.

The upper castes are also the ones who have also successfully converted their caste-capital into clean livelihoods and modern skills, as sociologist Satish Deshpande has argued in his essay ‘Biography of General Quota’. But when others are still in the process of claiming their fair share of power, resources and opportunities, the Brahminical-gene is anguished. We need ‘Brahmin-Gene’-stickers to show who we are. Is that not how the Brahminical-Gene behaved for ages—with display of all kinds of marks on the bodies to demarcate themselves from the others?

Delegitimising the Other and Denial of Resources

The playing fields were never equal; and even now, they are far from being equal. Merit, like any other acquired commodity, is not meant for free distribution. Merit is designed to discredit the ‘others’. For example, Bharti’s character in Gilli Pucchi, a Hindi short film, directed by Neeraj Ghaywan, is a touching portrayal of how a Dalit blue-collar worker is considered absolutely incapable of making a transition to the white-collar segment—even though she possesses all the necessary qualifications. In comparison, an upper caste woman, with no proven qualification, is considered more suited. A Dalit’s claim on clean work faces social delegitimisation. Dismissing the ‘other’ is integral to the Brahminical-Gene.

The Brahminical-Gene is not confined to Brahmins alone. It is a genetic disorder of feeling superior, which is structurally embedded in the caste system. Myths and economic resources are often deployed to claim that “we are superior to our equals and equal to our superiors,” as sociologist Dipankar Gupta has argued.

The structure of caste system does not permit sharing of resources. If we turn to contemporary Tamil popular cinema, violent assertion of the marginalised is repeatedly premised on contestation over resources, which have been traditionally denied to them. Conflicts arise when such resources, such as land or educational rights, are demanded.

For instance, Tamil film, Asuran (2019), directed by Vetrimaaran, begins with a fight over water. Dominant castes, who have installed an electronic pump for irrigation, are oblivious to the fact that ground water is a shared resource and installation of the pump will reduce the water level. Contestation over water is temporarily resolved by compelling the ‘lowly lives’ (as they are addressed by the upper castes) to enter into an unfair compromise. The ‘lowly’ has to take his slipper off and beg and plead in front of all the upper caste households. Towards the end, there is a profound statement from the suffering protagonist, who advices his son to take up education. “Land can be seized; money can be snatched but education cannot be taken away,” he says. Therefore, it is in the Brahminical-Gene to make education less accessible.

Another Tamil film, Pariyerum Perumal (2018), written and directed by Mari Selvaraj, opens with an elaborate punishment scene, where a dog belonging to the Dalits is tied to the railway track to be squashed. The idea is to show ‘them their place’ for entering into the fields that originally belong them, but have been misappropriated by the upper castes. Here, too, education is seen as emancipatory. It is the only path to emerge out of the vicious cycle of subordination and denial.

But the educational system favours the privileged castes, making it difficult for a first-generation Dalit to complete a degree. If education is a legitimate means to be upwardly mobile, no wonder that it such a contested terrain. To maintain status-quo and restrict mobility—rights to admission must be reserved only for the inheritors of ‘merit’. Discrimination must be reasserted at every stage to make things difficult for others. The suffering protagonist utters with regret at the end that “as long as you are the way you are and expect me to be the dog, noting will change.” Expecting others to be subservient is an important component of the Brahminical-Gene.

In Maamannan (2023), another Tamil film by Mari Selvaraj, Dalit children are punished to death by inflicting stones on their heads because they were taking bath in a well that is reserved for upper castes. Later in the narrative, one of the survivors gets into a feud, when his father is denied the right to sit by the side of a leader from the dominant caste.

The symbolic contestations take a different dimension in Tamil fil, Karnan (2021), again directed by Selvaraj, where the male protagonist explains the actual reason for atrocities against them. He says that the upper castes are not irked because they demanded a bus stop in their village. Their dignity was ‘robbed’ because Dalits have decided to walk with their head held high and fight. It is that resistance, that irritates the upper caste egos more than the act of appropriating upper caste names. Conscious of hierarchy, the fragile Brahminical-Gene is prone to getting offended when others do not bow down.

'A Different Kind of Justice'

The most nuanced and subtle expression of the distance between castes—paradoxically arrives after consensual sexual intimacy between a male Dalit police officer and a daughter of a higher ranked officer in the Hindi film, Bheed (2023) by Anubhav Sinha. The officer says: “My hands tremble while touching you. Justice is always in the hands of the strong; if it’s transferred to the hands of the weak, it’ll be a different kind of a justice”.

The distance, the denial, the difference, the demarcation, the deprivation, the dominance, and the dehumanisation has been so internalised over generations that the touch ‘trembles’, even after attaining some power and status guaranteed by the Constitution. It is the touch of the lower caste, after all. Justice is still not served by these hands even though it is allowed to touch.

At this point, it is relevant to cite a question that the Hindi film Article 15 (2019) throws at us: Do ‘they’ even exist in the definition of the nation? It is the nation that hides its deficiency of not providing safety equipment to Dalit drainage plumbers, and then accusing a social activist for writing content that instigates manual scavengers to commit suicide (Marathi film, Court, 2014)! To be dismissive of petty demises, defines the Brahminical-Gene.

The privileged Brahminical-Gene despises anything that would quantify their accumulated privilege at the cost of others. Disparities and disproportionate arrangements would be validated by numbers. There will be legitimate demands to extend and expand the scope of reservation. Hence, the Brahminical-Gene is averse to caste census.

Serving social justice is not in the DNA of the Brahmin-Gene. It wants to own ‘merit’ and disown the ethical baggage of social justice. Therefore, the constitution of the Brahminical-Gene is essentially un-constitutional.

The writer is a sociologist at Shiv Nadar University, Greater Nodia. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.