Sheer Irrationality of Three-Language Policy

On March 6, 2025, the Union Minister of Parliamentary Affairs and Minority Affairs Kiren Rijiju claimed that the proposed ‘three-language formula’ in the New Education Policy (‘NEP’) of 2020 was “good for the whole country.” The 2020 policy reiterates the ‘three language formula’, first introduced in the NEP of 1968, which mandated the teaching of Hindi as a language in non-Hindi speaking states. The new policy retains this formula with the slight alteration that it does not impose any particular language on any State. It allows state governments to choose the particular languages, with the condition that two of three languages are native to India.

The Tamil Nadu government, which has implemented a two-language formula despite the 1968 policy so far, has come under pressure from the Union, which has indicated that the state government must impose the policy to enjoy funds under the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan. However, Tamil Nadu has alleged this to be a “smokescreen” for Hindi imposition.

Most importantly, what is the necessity to impose this policy specifically in the South Indian states which have outperformed their counterparts in every academic parameter?

The wrong time

The fundamental question that arises is why the contentious three language policy is being sought to be implemented now? And the second question is why?

The stock market has crashed, the Foreign Institutional Investors have withdrawn from the Indian markets, a recession is suspected to be in place, rupee is showing its historically worst performance at 87 to 1 US dollar and unemployment is distressingly peaking. Most importantly, what is actually urgently required is a robust science education policy which should move towards challenging China’s science and technology dominance, having now taken the lead over the United States in 57 out of the 64 critical technologies.

The wrong reason

There is a fundamental constitutional conundrum to this move. Children in Hindi speaking north Indian states would only study two languages - English and Hindi. On the other hand, children from five southern states beside Maharashtra, West Bengal and Odisha have to learn three languages.

Where is the constitutionally mandated equality?

Most importantly, what is the necessity to impose this policy specifically in the South Indian states which have outperformed their counterparts in every academic parameter?

There are very fundamental reasons why any tinkering with the education policy of the Southern states would be working to their detriment. The southern states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka have, over the years, fine-tuned their education systems, and are surging ahead with impressive gross enrolment ratios (GERs), literacy rates and density of higher education institutions per capita.

Each language is a historical and cultural marker for the community. It gives voice to their histories and their cultures.

Not so subtle erasure of distinct peoples

Imposing the three-language formula on a large section of children’s population across India is bound to cause serious distortions in terms of how native languages are learned and inhered. For instance, the average Maharashtrian student would have lesser time on their hands and will naturally choose to pay lesser attention to their own mother tongue. If you diminish the capacity of Maharashtrian students of their time and capacity to soak into their own language, we are in effect marginalising Marathi’s history of being a separate language dating back to the 3rd century BC. You are also impeding the imbibing of Marathi literature through recorded verses, prose and scientific treatises which date as far back as the 13th century. You are gently forgetting the glorious tradition of the Warkari and other religious movements. You are also silencing the stellar contribution of Maharashtra to journalism, which commenced as early as 1832. You are slowly eclipsing the path breaking social reformist works of Jyotiba Phule and Savitribai Phule. You are obliterating the genius in the dramas of Vijay Tendulkar, the cinematic orations of Mohan Agashe and the songs of Purandare. You are, in effect, erasing a language.

What is language and what does it stand for?

While the proposed language policy was being hotly debated in the Constituent Assembly, Pandit Lakshmi Kanta Maitra made a very pertinent point. She recounted that when the founder of Pakistan tried to impose Urdu, violent demonstrations had erupted all over East Pakistan. On the accusation that the Hindu fifth column was responsible for the protests, the Muslim intelligentsia of East Pakistan belligerently countered Jinnah. “They said you are trying to throttle the language of Rabindranath Tagore. We are not going to tolerate it,” Pandit Maitra recalled. Jinnah, after seven days attempting in futile to impose Urdu with an Arabic script, retreated to Karachi.

The reason why language evokes such intense reactions is because language is more than a means of communication. It is the living heritage and an emotional bond with a community’s past and forms the collective consciousness of people.

Each language is a historical and cultural marker for the community. It gives voice to their histories and their cultures. When you try to obliterate a language, you decimate its history, its literature, its poetry, its music, its films, its culture, its cuisine and its fine-tuned sensibilities nurtured over centuries. Language is the medium through which the cultural identity, through its oral and written history, is transmitted generation to generation. For instance, the Tamil Brahmi script is found in the 900 years old temples of Ankor Wat in Cambodia, but its origins date back a further 1500 years to the 3rd century, BC.

The beauty and charm of our diverse languages

Instead of compartmentalizing languages, a culture of appreciating linguistics should be taught.

Having travelled, lived and studied across India, I had the good fortune to pick up, let me emphasise entirely voluntarily, Tamil, Kannada, Marathi, Gujarati and Punjabi and a workable understanding of Telugu. I learned all this in addition to the mandatory learning of Hindi and English.

Having grown up in Mumbai, I learnt Marathi by listening attentively. I love to hear Marathi being spoken. Each word pours out so much of a calibrated form of Sanskrit. Mumbai also gave me the opportunity to listen to and imbibe the Gujarati being spoken by Gujaratis as well as the Gujarati spoken by the Parsis. It’s a delightful comparison.

Then, there is Kannada, spoken in my mother’s home, so mellifluously fluid and gentle. Having lived a good part of my life in Delhi, I cannot but be fond of the direct robustness of the Punjabi language. Like the Bhangra, the words dance out in joy and gaiety.

What is to be encouraged is the appreciation of our linguistic diversity rather than to crib and cage languages into compartments.

I also grew up in Coimbatore and witnessed many political rallies. The speeches from the podium demonstrated that Tamil, like German, was perhaps the most phonetically powerful language in this part of the globe.

I am forever indebted to my parents for having spoken to me in my mother tongue Malayalam. I love the language and the myriad ways in which it is spoken in different parts of Kerala and the brutal sarcasm with which it is deployed. Sarcasm is a second nature to Malayalis. This irreverence has spawned a genre of sophisticated satire and humour in literature, cinema and theatre which, most unfortunately, gets lost in translation.

Malayalam cinema, thankfully, did not get ‘Bollywoodised’. It developed an independent, powerful and influential identity of its own. It has so much to offer in intelligent cinematic brilliance like Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s ‘Elippathayam’, the screen adaptation of Thakazhi’s ‘Chemmeen’, Shaji’s ‘Piravi’, Fahadh Faasil’s ‘Joji’ and so on. This list is fortunately endless and growing.

There is so much unique beauty, charm and artistry in each of our languages. What is to be encouraged is the appreciation of our linguistic diversity rather than to crib and cage languages into compartments.

Linguistic diversity: The source of our resilient democracy

A movie star with a bizarre and pedestrian bollywood logic had once said that since Hindi films are dubbed into regional languages, Hindi is the national language. There is, fortunately, an India beyond the narrow linguistic confines of Bollywood. That is the India occupied by linguistically disparate 1.4 billion people.

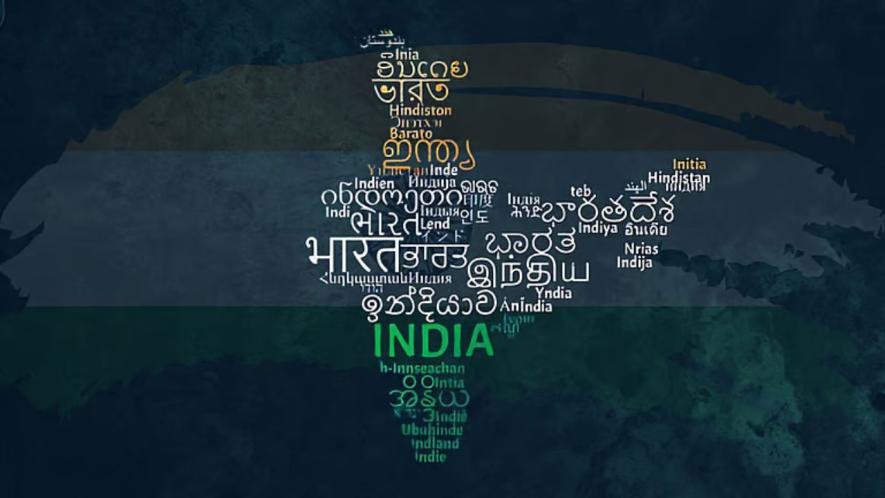

If we read our beloved Constitution, especially its Schedule 7, it will dawn that India is a ‘Union of States’ which has 22 official languages. India’s brilliant Constitution has welded together our linguistically disparate people successfully into one country. Language in our constitution is not meant to be an instrument of chauvinism or designed for display of linguistic superiority. It gave respect to our languages, guaranteeing linguistic diversity in order to effectuate the idea of unity.

It will be useful to bear in mind that Europe, which consists of 44 countries, has 24 official languages that are spoken. Here in India, there are 121 spoken languages, 22 official languages and there are, believe it or not, 19,500 dialects spoken as mother tongues. And we are still one country. That’s the most astounding achievement of our Constitution. It is time we are taught to respect that.

Santosh Paul is a senior advocate, Supreme Court of India.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.