Babies Crawl to Codes: Is David Černý’s Prague a Prophecy?

Kafka Head taken by author.

In a world where headlines shriek of corruption and ideologies are dished out faster than fast food, Prague offers an oddly medicinal — and medieval — antidote. The Czechs, of course, know their darkness, from Nazis to Cold War communists. But for this stranger from Bengal, the madness here comes beautifully sculpted. It clears a mind still fogged by airport announcements and the spicy din of desi political debate.

I'd only just arrived in Prague last year, my head brimming with half-digested histories. The March air was crisp, sunlight slanting gold across old, cobbled lanes. I was sipping coffee outside a repurposed factory in Prague’s Smíchov district—now a hub for artists—when a local curator named Kateřina leaned across the table and pointed at a pale-yellow building nearby.

“That’s a museum,” she said casually. “Lots of interesting sculptures. You might like it. But—” she paused, eyes glinting, “don’t tell them you’re here doing research. Especially not art research.”

I laughed, unsure if this was a local joke or just Prague being Prague. “Why?” I asked. “Is the museum off-limits to foreigners?”

Kafka Head Poster taken by author.

Kateřina smiled. “Not at all. You can absolutely go in. Just… don’t say you’re here for research. Especially if it’s about art. Otherwise, the ticket price jumps by fifty crowns.”

Kateřina explained that David Černý’s Mausoleum—his own personal museum—bends the rules of logic and taste, like everything he touches. At one point, many say, Černý had decided that regular visitors should pay less than art students or researchers. Why? Nobody knows. Possibly not even Černý.

That was my first introduction to David Černý; though relayed orally, it left enough of a mark to compel me to explore the artist for the rest of my time in Prague. Just then, Kateřina’s phone rang. “Have a nice stay,” she said, already halfway to the gallery doors. “And don’t overthink it. With Černý, the less you try to explain, the more sense it makes.”

I turned my gaze toward the building. The word mausoleum was scrawled on the façade. Just below it, a metallic baby was crawling down the wall—its face blank, smooth, a barcoded void. I didn’t realize it then, but these faceless babies were something of a signature.

David Černý by David Černý.

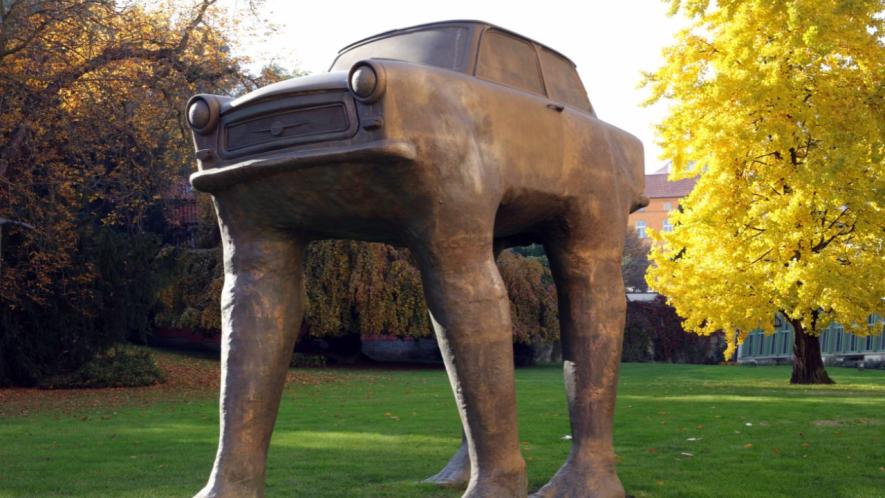

David Černý was born in Prague in 1967—a place where Kafka walked, revolutions brewed, and let’s not plunge into endless city history! He trained in art in his hometown but quickly began bouncing across the map — America, Switzerland — wherever his sculptures were least expected. His first major splash came in 1989 with a work titled Quo Vadis. It wasn’t a saint. It wasn’t even human. It was a morphed East German car — the kind once found puttering down roads in the GDR — reimagined with four human legs instead of wheels, marching toward the West.

The symbolism didn’t need a decoder ring. That was the year the Berlin Wall cracked open. People from East Germany were pouring westward. Černý’s sculpture was both absurd and piercing. Quo Vadis — Latin for “Where are you going?” — was more than a title. It was a question aimed at history itself.

Since then, Černý has rarely missed a chance to be unpredictable. Or divisive. Or both.

In 2012, while London was preparing for the Summer Olympics, Černý turned an old double-decker bus into an art installation called London Booster. It didn’t move on the road — it did push-ups. Real, mechanical, slightly ridiculous push-ups. That red bus had spent twenty years cruising through Britain and a stopover in Netherlands before Černý’s studio table.

The installation became a hit, a kind of wheezing symbol of perseverance. After the Olympics, it returned home and now rests outside a Czech agribusiness HQ. Černý had transformed a bus into a witty jab, a spectacle, and a strange time capsule, all in one go.

Quo Vadis by David Černý

The Babies of Žižkov

Spend enough time in Prague, and you'll inevitably cross paths with them. And once you do, they're hard to forget.

They’re (okay, most of them) not in a playground. Not tucked inside a gallery. They’re crawling—slow, massive, eerie—up the Žižkov Television Tower. Several fiberglass infants, their faces smooth and stamped with what looks like a bar code or some machine panel. They don’t smile. They don’t cry. They climb. Perhaps they wished to be on solid ground, but that never happened.

Černý first installed them in 2000 as part of a temporary exhibition. But Prague, being Prague, fell in love with the weirdness. Locals liked them. Tourists stared. And so, the babies stayed. (Well, the originals were removed and replaced with sturdier versions in 2017 — even surrealist babies need maintenance.)

Miminka — Czech for “babies” — is what they're called. They're ambiguous, unsettling. Their featureless faces hint at a future where identities are obsolete, replaced by mere codes, pure data. Perhaps these aren't babies crawling towards childhood, but away from it.

You’ll find them elsewhere too. In parks. On museum walls. Sometimes belly-down on the ground, crawling in formation like a new species. Černý’s babies are mobile metaphors — glitching across public space, hinting that innocence may already be under surveillance.

London Booster by David Černý

Kafka's Spinning Head

Just outside the Quadrio Shopping Center in central Prague, Franz Kafka’s head is turning. Not metaphorically — though, that too — but physically rotating in a slow, perpetual dance of disorientation.

Towering over passersby at 11 meters high, the sculpture is made up of 42 glistening stainless-steel layers, each capable of independent rotation. Every 15 minutes, the panels whirl and align, breaking apart and then reassembling Kafka’s face in haunting, machine-precision synchrony.

Its Metropolis meets Metamorphosis

The irony is deliberate. Kafka, the master of inner claustrophobia and bureaucratic paranoia, now stands polished, monumental, and — let’s face it — rather Instagrammable. In this age of surveillance capitalism and carefully curated selves, what could be a more fitting tribute to the writer of The Trial than a face that never quite settles?

Critics gave it mixed reviews. That it reduces Kafka’s deep introspection to mall-side spectacle. Is it a betrayal? Or a perfectly Kafkaesque irony — the man who feared faceless power now rendered as a fragmented face outside a consumer palace?

Whatever your verdict, it draws a crowd. Like much of Černý’s work, it doesn’t ask for agreement — just attention.

Žižkov Tower 01 taken by author.

Barcodes and Questions

One set of these “Miminka” babies — fiberglass mutants with blank faces — still crawl across the Žižkov TV Tower, visible from miles away. Another gang lies flat on the grass near Kampa Park, sniffing dirt like cybernetic toddlers bred in a dystopian daycare.

And always, the barcodes. Not eyes, not mouths. Just… codes. Černý never explained. Which is exactly his point.

Are we — the “civilized,” the algorithm-fed, the endlessly-scrollable — becoming barcoded beings ourselves? Trading senses for sensors? Feeling for feedback loops? Will Kafka’s face keep spinning until we recognise it not in the chrome, but in ourselves?

One might think this is all too much, too gloomy. But in Prague, the city of a thousand spires and equal shadows, melancholy comes with the architecture. Černý merely adds the punchline — often vain, often vital.

And as the sun dipped behind the Vltava, casting long shadows on the babies, Kafka’s fractured head turned once more.

Steel lips parted. No words came out. But if they had, I imagined him whispering —

“Are you watching? Or just seeing?”

Pijus Ash is a writer and researcher based in Kolkata, with over two decades of experience in journalism. He is associated with Udbodhan (Ramakrishna Math) and the 'Centre for Indological Studies and Research'.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.