Remember Gandhi, India’s Most Eloquent Voice for Peace and Harmony

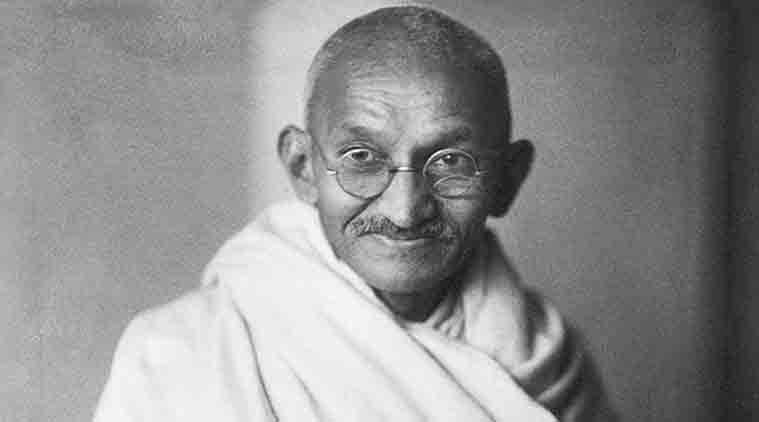

Image Courtesy: The Indian Express

Precisely seventy-three years ago, three bullets fired from the gun of a Hindutva fanatic, Nathuram Godse, silenced the most eloquent voice for peace and harmony in the world. That voice was of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He came to be known as the ‘Mahatma’, first in January 1915 during a reception ceremony at Kathiawad. Later, the sobriquet was popularised by Rabindranath Tagore through a letter written in February 1915.

The moniker stuck to Gandhi not just because he wore a loincloth and had a tonsured pate, but because of his great experiment in politics wherein morality, non-violence, and a supreme onus on means as opposed to ends, acted as the most important signposts. Ironically, all these were virtues that political theorists from the time of Chanakya, Thucydides, Machiavelli and Hobbes had warned against. Yet, Gandhi decided to buck the trend and take on the British imperial machine with these un-experimented ideas.

The successes and the failures he achieved are there for history and historians to judge. What makes Gandhi and his politics unique is that his age was coeval with that of fascism and two horrific world wars that caused the death of millions and the imperial purloinment of vast swathes of the globe. Despite the degree of violence, Gandhi stuck to his notions of non-violence as boldly as Hitler stuck to his mad pursuit of fascistic violence. The great Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm was right to call this period the ‘Age of Extremes’, but he did so without cognisance of this crucial fact.

Gandhi was undoubtedly the most prominent leader of the Indian anti-colonial nationalist movement. He came to India when the masses, for the first time, entered into a confrontation with the British imperialists. He played a significant role in this awakening by launching the Non-Cooperation movement in September 1920 when the British reneged on their promise of granting self-rule to Indians after the First World War. Unlike other upsurges against the British, from the Great Revolt of 1857 to the Swadeshi movement of 1905, the Non-Cooperation movement spread across the entire map of the country. As far as Assam, Gandhi was christened as ‘Maharaja’ by the beleaguered tea plantation workers. The movement also marked an epistemic break as it broke away from the soft yet solid liberal economic critique of empire and the cultural-nationalist model of the early twentieth century. The break from the latter was even more marked because of Gandhi’s manoeuvre to bring Hindus and Muslims together on the Khilafat platform, which launched along with the Non-Cooperation Movement against the dismemberment of the Ottoman empire.

****

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born in 1869 in Porbandar, then part of the Kathiawad state, and now in Gujarat. He was born into a family of Modh Banias, a merchant caste, who had been for three generations entrusted with the position of nobility in Kathaiwad. Like most merchant families of the time, he was brought up in a religious environment. In his autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, he writes that he got a profound impression of ‘saintliness’ from his mother. She belonged to the Parnami sect, which philosophised Hindu and Muslim religious doctrines and gave equal status to the scriptures of Vaishnavism and the Koran.

Gandhi learnt the idea of penance from his mother, who believed in taking the ‘hardest vows and pursuing them unflinchingly’. He added various philosophical elements to his experience of eclectic Hinduism from other religions such as Buddhism, Jainism, the theosophists, the New Testament and a keen reading of Tolstoy, Ruskin and Thoreau.

Gandhi’s plural religious and cultural experiences shaped his conscience, spiritualism, and the idea of service. Though he called himself Sanatani, i.e., an orthodox Hindu, he rejected the notion that religion should be interpreted in doctrinal and puritanical terms. His faith was based on individual experiences unmediated by any official clergy. To this effect, Gandhi wrote in his Young India, “…I try to understand the spirit of the various scriptures of the world. I apply the test of ‘Satya’ (Truth) and ‘ahimsa’ (non-violence) laid down by these very scriptures for their interpretation. I reject what is inconsistent with that test, and I appropriate all that is consistent with it.” For him, the spirit of the texts was more important than the actual written content.

Philosopher Akeel Bilgrami has argued that Gandhi extended his ideas of religion to politics and denied the sequestration of religion from politics. For Gandhi, politics was subordinated to religion and politics devoid of religion was nothing but a soulless manifestation of the idea of social change. This extension allowed him to base his political philosophy on the pillars of Satya (Truth) and Ahimsa (Non-violence). Gandhi’s criticisms of the modern state, science and modernity were all embedded in such a conception of religion.

For Gandhi, the idea of Satya or Truth was not a modern conception of objective reality or truth. He put a supreme premium on the role of human subjectivities to experience truth with conviction. For him, politics was a personal endeavour to provide exemplary service to others; therefore, truth should not aim to homogenise. Instead, it should conserve the pluralism of societies. He conceptualised ahimsa at a deeper level to include its manifestation in inter-personal relations, doctrinal application, propositions, scientific endeavours, and the idea of the state.

Gandhi argued that all doctrines produce violence by classifying human beings into different categories. The state converts human beings into citizens and population, while religious doctrines convert people into followers and non-followers, and political ideologies transform individual existence into ideologues and opposition.

Drawing from satya and ahimsa, Gandhi introduced the ideals of satyagraha (passive resistance) and satyagrahi (one who offers satyagraha). A satyagrahi was seen as someone with a strong subjective religious experience and who was ready to dedicate one’s life solely to the service of others. Satyagraha meant the courage to speak against injustice and show higher moral power to change the oppressor’s heart. It was deemed a ‘truth force’ or ‘soul force’, an intensely personal act against injustice. Therefore, it was not only about fighting the colonial state but also service to set an example before society. He started satyagraha against the British government, not believing that the rulers of a different national origin must be oppressive. He showed the example of the princely states to drive home the point that the rulers from our society can create a more oppressive and authoritarian rule.

To fight the evils of Indian society, he started ‘constructive work’ centred around promoting Khadi, religious harmony, Swadeshi, and social uplift. It was not optional, but his primary strategy was to bring the essential elements of satyagraha among satyagrahis: self-discipline and service.

Gandhian ideas found in the colonial state an amalgamation of all evils associated with modernity. He deemed it bureaucratic, based on science and objectivity, overcentralised and an impediment to the march towards freedom. He used the weapon of satyagraha to counter this colonial state in India.

His experiments with satyagraha against the introduction of the Rowlatt Bills of 1919 failed due to the cases of violence registered in many states, including his home state Gujarat. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre during the Baisakhi celebration stunned the whole nation. Young revolutionaries and nationalists responded to it in terms different from Gandhi. While Gandhi called the Rowlatt satyagraha experiment a ‘Himalayan blunder’, he did not lose faith in truth and non-violence and the capacity of Indians to adopt them.

He launched another satyagraha on a bigger scale and included the Khilafat cause in the national struggle to resist the colonial government and forge a unity of Hindus and Muslims, which was fractured by the colonial state, especially after the declaration of the partition of Bengal in 1905. When satyagrahis indulged in violence at Chauri Chaura, Gandhi withdrew the movement. His rising popularity disturbed the confidence of Hindu and Muslim communal politics. The communal harmony seen among the Hindus and the Muslims during the Non-Cooperation movement was barely apparent in any future battles against the colonial state.

Gandhi creatively used the instrument of satyagraha for the temple entry movement, i.e., the Vaikom Satyagraha, Civil Disobedience movement, Kheda and Bardoli Satyagraha and so on. He succeeded in socialising Indians in the political struggle against colonial rule through constructive work and by changing many of the structures of the Indian National Congress.

The use of satyagraha radically restructured Indian politics. This mode of protest inspired by religious idioms instead of communally-inspired popular religiosity mobilised masses and established satyagrahis as a far superior moral force. Whenever satyagrahis showed signs of deviation from its fundamental principles, Gandhi restructured the politics to engage them in constructive works to experience truth.

***

Gandhian methods also created many political dissenters in India. Within a decade of his rise, competitive Muslim-Hindu communalism propagated ethnic nationalism in the country. Gandhi and the communal leaders used religion as a source of their politics, but there was a fundamental difference. For the Muslim League and Hindutva fanatics, religion was embedded in history because, for them, history was nothing but a warring tale between religious groups. On the other hand, Gandhi used religion to cultivate the moral foundations of an individual. He called the Gita the ‘spiritual guide book’ and interpreted it to bring the point that it spirit reveals the futility of war. Meanwhile, for Hindutva leaders, the Gita legitimised their goal to militarise the Hindus.

On the eve of the Second World War, when the Jews faced genocide at the hands of Hitler, Gandhi accused him of far surpassing the tyrannical kings of the past in their pursuit of madness. He wrote that Nazism “was the religion of exclusive and militant nationalism that legitimated and rewarded any act of inhumanity as humanity”. On the question of Palestine, despite conceding that the Jews had suffered persecution for ages, Gandhi remained categorically opposed to the call for a national home for the Jews in Palestine. He believed that Palestine belonged to the Arabs, and it was inhuman to impose the Jews on them. For Gandhi, the Palestine of Biblical conception was not a geographical entity; it was in the heart of the Jews. And offering it to the Jews was nothing but a crime against humanity.

We can juxtapose these two instances with Hindutva. First, when Hitler was murdering Jews, Hindutva icons in India looked up to him and longed for a ‘final solution’ for Indian Muslims. Ironically, modern-day Hindutva looks up to Israel as a model state! Second, the mad pursuit for the Ram Mandir at the site of the demolished Babri mosque by Hindutva organisations sits ill with Gandhi’s conception of religious territorial sites. He would have thoroughly opposed the demolition and acquisition of the Babri masjid to build the Ram mandir, likely reasoning that Ram resides in the hearts of Hindus and needs no demolition of a holy place for his homecoming.

Since Gandhi posed a huge impediment to communal schism, the Hindutva fanatics hatched a plan to kill him. Sardar Patel, then Home Minister, concluded the role of Hindu Mahasabha directly under Savarkar in the planning and execution of the assassination plot. Savarkar was also indicted by the Jivanlal Kapur Commission set up in 1965. However, he was acquitted by the court in the absence of corroborative evidence.

Seven decades after Gandhi’s gruesome assassination, the forces that planned and executed this heinous crime are ensconced in power. India has seen open celebrations of his killer, Nathuram Godse, and glorifying biographies of Savarkar—the progenitor of Hindutva. In these trying times, we must recall Gandhi more than ever. We must recall his attempts to stop the communal conflagration by intervening in the riot-hit areas, a feat no politician, then or now, has ever replicated. Today, India has much to from the life of Gandhi. This would help us unlearn much of what has been fed to us by the current ruling dispensation.

Shubham Sharma is an independent research scholar. Satyanand Jha Vatsa is a doctoral candidate at the Department of Sociology, South Asian University, New Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.