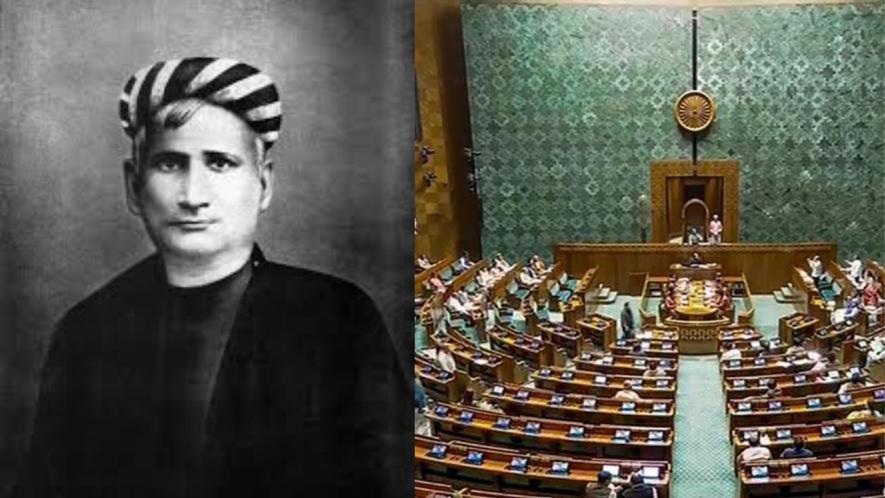

Baffling Silence Over Bankim-da’s Bigotry

Image Courtesy: PICRYL

The Prime Minister addressed Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay as Bankim-da in Parliament. Such a solidarity slip has resulted in an outbreak of memes in Bengal. In one of those memes, the Prime Minister is seen standing next to Chattopadhyay and asking: “Will you have some tea Bankim-da? I make very good tea”. The ruling party’s selective appropriation of cultural icons and their work that favour their line of nationalism—is understandable. But what is really baffling is the silence of the intellectuals around Chattopadhyay’s blatantly communal agendas.

I shall arrive at Chattopadhyay’s novel, Anandamath, in the latter half of this article. Let us begin by considering some of his less popular and less circulated essays on nationalism and religious identity that were published between 1875-1885. There is a tripartite objective found in these essays: first, to victimise the ‘self’; second, banish the ‘other’; and third, to justify revenge against the ‘other’.

Chattopadhyay's project is very much in sync with the Hindutva narrative. According to him, there is loss of ancient glory—followed by the loss of pride and wealth under the Muslim-rule in medieval times—necessitating armed emasculation to show them their place. In the task of constructing and criminalising the ‘other’, violence is not a hidden agenda but an overt means to that end.

Chattopadhyay’s nationalism is about staging supremacy to regain power and Hindu supremacy. There are two interrelated trends in his project. One is that of cultural homogenisation and another is Hindu-heroism that appeals to communal vengeance. The latter idea legitimises violence against Muslims. And the former idea emerges out of an imagined Hindu belief that what is good for every Hindu, is good for me. Cultural diversity, has always been seen as obstacle in the path of Hindu-solidarity, anyway.

Bahubal and Bidharmis

Several essays of Chattopadhyay are loaded with portrayal of imagined victimhood—the sort of Hindu victimhood that instigates violent action. He emphasised several shortcomings among the Hindus: their emasculation, their sufferings, their lack of unity, and their lack of history. These ‘lacks’ eventually transpire toward a dire need for unified Hindu religious mobilisation.

Bankim excessively valorises hyper-masculine physical strength (Bahubal) as a necessary tool of revenge to be channelized towards religious polarisation. In his writings, Muslim misrule is: sin-ridden (papistha), wretched (naradham); treacherous (biswashanta); and a stain on the face of humanity (manusya-kulakalank). Bankim repeatedly constructs the Muslim as the religious other (bidharmi), as outsider (bideshi) and as oppressors (parapirak). Such a construction is invariably followed by criminalisation of the religious-other, and eventually a call for revenge to protect Hinduyani.

In his essay, Bangalir Bahubal (Bengali’s Muscle Power), Chattopadhyay makes a series of claims on emasculation of the Bengali Hindus. He blames it on the ecology of Bengal—the moist and fertile land, and on faulty dietary practices. Bahubal is a unique combination of ‘enthusiasm’, ‘unity’, ‘courage’ and ‘perseverance’ that has to be regained for progress. Bahubal fits aptly with the narrative of hyper-masculine nationalist imagination aiming to avenge. In fact, it is a prerequisite.

Another essay, Bharat-Kalanka (India’s Taint), starts with a question: why have we remained in that state of lost-independence for so long? Because the current generation lacks the virility and vitality of Hindus from the ancient times. A regressive revivalist politics of projecting glorious Hindu past is amply clear in some of his essays. And what has turned Hindus into a weaker religious community? The answer lies in another narrative of lack and loss of freedom for several centuries, which calls for power to be regained. In that process, minorities must remain subdued. His essay ‘Bahubal and Bakyabal’ says: “In case it is a matter of difference of opinion, minorities must obey the majority.”

In another essay, titled Bharatbarser Swadhinata ebong Paradhinata, (India’s Freedom and the Loss of it), Chattopadhyay’s anti-Muslim rant becomes even more straightforward. He writes, “If a country is ruled by a king who originates from another country, then that country and its countrymen stand defeated."

This resonates so well with the core principle of Hindutva ideology: Hindustan is ‘exclusively’ for Hindus, and Muslims are either outsiders or invaders or intruders or second-grade citizens. His search for authentic history, leads him toward the ancient past, and predictably so.

Chattopadhyay also hails upper-caste dominance in ancient India as something that is more desirable and relatively better than the rule of Muslims, because even if Brahmins and Kshatriyas were exploitative, they were “our own people”. The idea of the self in his essays on issues of nationalism and identity is solely determined by religion, and religion alone.

In Banglar Itihas (The History of Bengal), Chattopadhyay claims that the cause of Hindu misery is a consequence of history of Bengali Hindus being written by Muslims. To quote him, "Any Bengali, who considers these narratives as Bengal’s history, is not a Bengali. Those who accept that History of the humbug, deceitful, anti-Hindu Muslim rulers—are not Bengalis.” He would add: “On many occasions, the prosperity of others’ could be detrimental for us. When that happens to be the case, we must ensure that others do not receive the chance to prosper.”

Militant-Nationalism in Anandamath

The contribution of Chattopadhyay in single-handedly curating Hindu nationalism is often less recognised, particularly by secular Bengali intellectuals. Because claiming his communal credentials terribly undermines the progressive and enlightened image of 19th Century Bengal. Therefore, we love to ignore how he fictionalised a revenge narrative that is blatantly communal. Anandamath is fundamentally fundamental—a text that upholds and celebrates of Hindu militant nationalism.

Anandamath offers a wa -cry in the form of Vande-Mataram and also a personified figure of worship: Bharat Mata. Chattopadhyay invented a profane goddess, devoid of traditional divinity and mythology, who demanded protection and sacrifice from her santans (children). He single-handedly curated a living symbol of pan-Indian Hindu-solidarity—much before it was actually born. He prepared a war script in the name of the holy mother, and penned a war cry, which is far more effective than ‘how’s the josh’.

In that dogmatic scheme of things, Vande Mataram is more of a religious war cry to establish Hindu glory, before it became a political chant for freedom against the British. Throughout the freedom movement Muslims have refused to utter Vande Mataram for a valid reason. And compelling Muslims to utter it during public lynching, therefore, has a long history.

The objective of the Chattopadhyay’s fictitious war was not to win freedom from the British. Its actual purpose was to fight and win a communal war. There is no iota of ambiguity in his anti-Muslim stance in Anandamath: “...unless we drive out Muslims, how can we save the religion of Hindus?”

In the third part of the novel, when the movement gains momentum, there is yet another horrific, graphic and glorified elaboration of communal acts by the Santans. The santans started sending their agents to the villages to convert, and freely divide their spoils. They go to Muslim villages and set their houses on fire. When Muslims are desperate to save their lives, santans rob their belongings to redistribute it amongst their Hindu disciples. Such a brutal attack is then hailed as a positive and promising path to establish Hindu rule.

In the tenth episode of Aandamath, Chattopadhyay further adds that a Muslim king, who is incapable and intoxicated, needs to be dethroned to protect Hinduyani. It leaves little doubt that the demon-killing chant of Vande Mataram: ‘…though million hands hold thy trenchant sword blades out’—is not targeted against the British.

The fourth episode of the second part of the novel ends with a genocidal desire from one of the leaders of the movement, who says: more than wanting to rule, we want a complete massacre of the minorities across generations.

Several historians have argued that Chattopadhyay’s hatred toward Muslims was limited to, and focused upon exploitative and tyrannical Muslim rulers, and not toward common Muslim subjects. There are no reasons to believe that he was selectively communal. The Muslims assaulted in the wake of Hindu rule in Anandamath were common Muslims and not the ruling elite.

In a strange winding logic (or the lack of it) toward the end of the novel, the readers are made to believe that mass-education to be spread through the British initiative will eventually help the cause of the spread of Sanatan Dharma—leading to Hindu revivalism.

Therefore, the British, unlike Muslim rulers, are seen as ‘mitra-raja’. The British were desired collaborators for Hindu progress. Chattopadhyay's ideological drift is bound to offend any current anti-Macaulay stance that is trending. But that is alright, when rendering of cultural icons are mostly selective.

(All quotations are translations done by the author from Bengali from Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s collection of essays: Bankim Rachanbali. Most of the essays cited here were published between 1875-1885 in various Bengali journals, such as Bangadarshan, Prachar, etc.)

The writer is an academic. The views expressed are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.