Punjab Elections: Even After Historic Struggle, No Poll Campaign on Farmers’ Issues

Sitting on a cot, Harbhajan Singh takes a nap awaiting calls from his sons settled in Britain and Canada. The call brings a beaming smile to his face. For years, Singh toiled hard to send them there. “It’s their income which made me relax. I was in debt for years. I had taken loans worth Rs 7 lakh in the early 2000s. The interest on the loans was such that entire income drained in paying the interest, leave alone the question of paying the principal amount.”

The story of Singh, a resident of Bhotna village in Barnala district of Punjab resembles almost all villages in state where the young population has chosen to migrate owing to widespread unemployment and exorbitant loans on families as agriculture remains non-profitable.

Contrary to the rampant distress, the poll campaign of political parties is silent on-farm issues even after the farmers of the state fought ferociously for a year against contentious three farm laws at the borders of the national capital. Modi government repealed the laws but still remains non-committal on other issues like forming a committee on minimum support price with clear terms of reference, quashing criminal cases against farmers during the agitation and compensation to kin of deceased farmers in the struggle. Still, no party seems interested in discussing these issues, including bringing the peasantry out of distress.

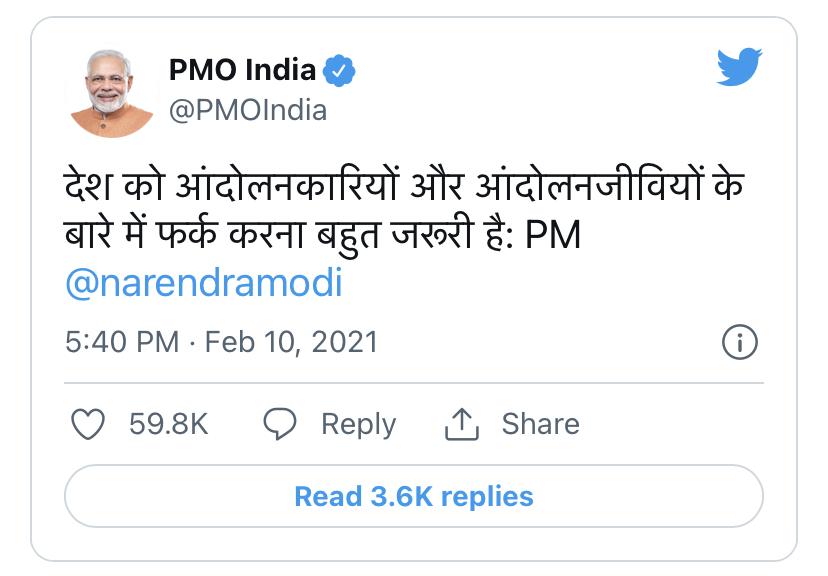

When asked about the silence of parties, Singh quickly responds, “This reaffirms our belief that corporates control the political parties. We had not forgotten days when we were called Khalistani, Tukde Tukde gang and even andolanjeevi. First, they denied us recognising us farmers but later accepted our demands.” During a discussion in Rajya Sabha, PM Narendra Modi had referred to farmers leaders as andolanjeevi on February 10 last year.

However, many families were not lucky enough to send their children abroad. Laden with massive debt, some farmers, whose relatives are uncomfortable about talking about their ordeal, chose to end their lives to get rid of humiliation by lenders. The village saw over thirty suicides overdue to mounting loans and fading incomes.

Sukhdev Singh, block president, Bharatiya Kisan Union (Ekta-Ugrahan), told NewsClick that the administration has denied that the farmers died due to debt. “We waged a struggle here to force the administration to accept these suicides and get compensation.”

A study conducted under the collaboration of Punjab Agricultural University (Ludhiana), Punjabi University (Patiala) and Panjab University (Chandigarh) revealed that during 2000-2016, 16,606 farmers committed suicides owing to mounting loans and decreasing income amid volatile weather conditions like hail storms and rains, attack by pests.

A conversation with farmers’ leaders and agriculture economists suggests that political parties' pressure to talk about distress eased out after some farmers’ organisations formed their own political entity, Sanyukt Samaj Morcha. Coupled with this, they also argue that the lack of agriculture policy worsens the affairs of farmers.

Darshan Pal, president of Krantikari Kisan Union and an important architect of farmers’ agitation at Delhi’s borders conceded that political parties are not discussing the issues of agrarian distress. Talking to NewsClick in his home in Patiala, he said that a general disinterest persists in political parties and voters over issues.

He said, “Parties are not discussing the issues because they are more interested in personality-based elections. They are facing a crisis in their organisations too. First, we saw it in Congress where the sitting chief minister resigned. The voters are not interested because they never saw poll promises being realised. So, it created a disappointment among them. We should also look beyond the question of elections. A general trend persists that farmers and workers organisations have struggled with governments only after their formation. We struggled during the Amarinder government and did achieve something. However, in previous one and half years, the attention of farmers shifted to centre after it brought farm laws.”

Replying to a question on indebtedness and associated suicides, he said that the question would need serious realignment and consolidation among farmers’ organisations in Punjab. “As far as the question of indebtedness is concerned, I can assure you that Punjab would see a big movement by the end of 2022 or the first months of 2023. The farmers brought the farming community together and put issues into focus, and the next phase should be to consolidate the movements, unify the organisations and go ahead with a clear understanding of issues. It would take a few months of preparations, but we will wage a series of protests at the end of this year. We are finding that farmers families, on average, are under the debt of Rs 9 lakh per household. So, the task is immediate.”

Dr Paramjit Singh, who teaches economics at Panjab University, Chandigarh, finds a slew of reasons why farmers’ issues are not discussed at length even when they waged a historic struggle against contentious three farm laws at the borders of the national capital. Talking to NewsClick in the plush and sprawling campus of his university, Singh said that the question of the peasantry cannot be resolved till the time it is seen as a whole, and the complexities of the class structure within peasantry are ignored.

“When we talk about the historic struggle of farmers, we must acknowledge that it has successfully exposed the nexus of politicians and big business which wanted to open the agriculture sector in Punjab to corporate capital. We must also realise that the rich peasantry primarily led the agitation, which successfully mobilised sections of small and marginalised farmers through populist slogans. The movement's mandate was to repeal the three farm laws, and the agitators eventually succeeded after PM Modi announced their repeal. But we have so far maintained the status-quo as far as the resolution to the agrarian crisis is concerned. The mainstream political parties do not talk about agrarian issues raised by the rich peasantry because they only constitute about 6 per cent of the overall peasantry and hence are not much concerned with the poorest of the poor in Punjab. This is one of the reasons that even after the agitation, mainstream political parties turn a blind eye to the agrarian crisis,” Singh said.

He adds, “Hence, parties recognise small and marginalised peasants, not as peasants but a section of the peasantry which could be lured through the announcement of freebies. The political populism of mainstream political parties will only deepen the crisis of the Punjab economy even if they fulfil half of their promises after elections. Due to petty political interests, the mainstream political parties, on the one hand and the rich peasantry, on the other, have no intention to permanently resolve the crisis of small peasantry and agricultural labourers. So, the peasantry in Punjab was in crisis, it continues to be in crisis, and it may remain in a crisis in the future too, because Punjab has no fundamental plan to bring the real victims of the crisis out of their misery. The one aspect of the crisis of peasantry in Punjab is the crisis of crop diversification. Johal Committee-I (1986) and Johal Committee-II (2002) have recommended crop diversification. The governments have not implemented these.”

He continues that, “Moreover, when we analyse the agrarian crisis, apart from crop diversification and indebtedness, the challenge is to put small peasantry in alternative means of livelihood because agriculture is no longer profitable for them. No political party is talking about providing alternate employment opportunities to poor peasants and agricultural labourers. Instead, we are witnessing the Chief Minister of the state imitating PM Modi’s 2014 campaign, creating an image of a poverty-ridden childhood. These antics are to mobilise Dalit votes, but he too would not be dealing with the real questions of the poor.”

Singh highlights that the farmers also lost track after a section of leadership formed its political party, Sanyukt Samaj Morcha. Now, when you look at its manifesto, you find no point where it has talked about marginalised farmers, agricultural labourers and non-farm rural poor. The marginalisation of the issues of the small peasantry and agricultural labourers is rampant even among the peasant unions such as mainstream BKUs and its different factions, including BKU Rajewal from the 1980s.

Prior to BKU, Punjab saw Lal Communist Party Hind Union, which fought a valiant struggle for land reforms, the Muzara (tenants’) movement. They realised the importance of the slogan “Land to the Tiller”. Due to its efforts that 16-lakh acre land was redistributed among the tenant farmers in 784 villages in erstwhile PEPSU. The Lal Party emphasised addressing issues of inequality at the village level. It fizzled out after ideological differences.

When BKU emerged as a leading peasant union, it narrowed down the scope of peasant movement to two demands; fair and remunerative prices and state-backed subsidies. This was never a plan for small and marginalised farmers as there could sell only a tiny proportion of their output in the market. However, when the price of crops increases which is the sole output of poor peasantry, the prices of all the remaining goods for which they are dependent on the market also increases, pushing them deeper into the vicious circle of poverty.

Singh added that “I am again emphasising that marginalised peasantry and agricultural labourers cannot be brought out of crisis unless they are provided alternative means of livelihood in capital dominant production structure and relations of Punjab agriculture. The rapid mechanisation of production has displaced thousands of permanent agriculture workers as one can now cultivate casual labour. In the capitalistic mode of agriculture, one is entirely dependent on the market for inputs and output. I understand that as long as peasantry remains a united front against neo-liberal corporate nexus, they can put strong pressure on political parties over the real issues of the agriculture sector. Along with that, they need to join hands with the urban working class and pro-people activists to provide better livelihood to the peasantry and working poor.”

Sukhpal Singh, a principal economist at Punjab Agriculture University, told NewsClick that the movement successfully pushed the crony capitalism, which wanted to control the production and marketing of agricultural products in rural India. Still, the silence of political parties even after historic struggle should be seen along with inherent flaws in their understanding. “The political parties are not talking about farmers’ issues simply because they understand that without corporate, there can be no resolution of agrarian crisis. Secondly, they believe that the current system has all answers to the crisis, but individual ministers are at fault. So, they often engage in mudslinging.”

“However,” he continues, “The fact remains that the state does not have its own agriculture policy that should mandate resource usage judiciously. Post green revolution, we find corporate control tightened over agriculture as they control the supply of inputs. Even after 17 years, the National Commission on Farmers report has not been implemented. Similarly, successive Punjab governments did not implement their report on crop diversification or MSP. Both failed collectively. To bring the state to adopt diverse crop patterns, it needs to dedicate resources, research and development but nobody is willing it.”

He added, “The relief to farmers in present set up can come up if the government reduces the fixed expenses through its intervention. For example, if the state can provide tubewell in the public sector, it may ensure proper water usage reduces expenses. But it needs to develop other interventions to reduce the costs in non-agriculture sectors. The farmers spend a significant amount of their incomes on education and health. So, good schools, universities, and hospitals are a must if we think anything about providing relief.”

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.