A Liberal Democracy in an Authoritarian Groove

On Tuesday, Additional Sessions Judge Kamini Lau of Delhi’s Tis Hazari court made a stirring statement in defence of, among other things, the right to protest, in the context of the way Parliament has of late been functioning. She was hearing the bail application filed by Bhim Army chief Chandrashekhar Azad.

Justice Lau was scathing. She excoriated the Delhi Police for failing to produce evidence backing its claim that Azad had indulged in violence at a rally in Delhi against the Constitution Amendment Act (CAA), 2019, while opposing his bail plea. But that was just for starters. She underlined that it was one’s “constitutional right to protest”, especially when inside “Parliament, things which should have been said were not said”. That was the reason, the judge said “why people are out on the streets”. “We have full right to express our views, but we cannot destroy our country.”

Delhi Police were behaving, she said, as if the Jama Masjid area was in Pakistan, when its counsel opposed bail saying Azad had staged a dharna at Jama Masjid. “What is the problem with going to Jama Masjid? What is wrong with dharna? It is one’s constitutional right to protest. Where is the violence? Have you read the Constitution?” This was strong stuff.

On the second, and final, day of the hearing, the judge had more to say in the same vein. She wrote in her order: “…fundamental right to peaceful protest is guaranteed by the Constitution, which cannot be curtailed by the state…While exercising our right to peaceful protest, it is our duty to ensure that no corresponding right of another is violated”. The order also said, “Violation or destruction of property is totally unacceptable and for any kind of damage to private or public property during the protest, it is the organisers who would be responsible for the said damage and liable to compensate for the said loss.” But the order noted that no assessment had been made of damage and there was no direct evidence to link Azad with damage to public property.

When the Delhi Police counsel read out six tweets, which he considered incriminatory, she commented on only two. In respect of one, which said Prime Minister Narendra Modi “brings the police when he is scared”, she said, Azad “should not disrespect the PM like this”. In respect of another, which said, those “who are inciting violence are from the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh)”, the judge said, “Why name RSS and other organisations? Talk about yourself. Talking about others can incite people.”

Despite making observations overwhelmingly in favour of Azad and against the police, the judge imposed bail conditions, which themselves are draconian, quixotic and prima facie unconstitutional. She granted Azad bail on the stipulations that he should not commit “similar” offences, after dismissing the prosecution’s contention that any offence had at all been committed; and should not visit Delhi till the Assembly elections there had got over, other than for treatment. It was also stipulated that he had to present himself to the station house officer at the Fatehpur police station in his home district of Saharanpur.

Noteworthy in all of this is the complete disconnect between the observations of the judge and the bail order. It would be interesting, though unfruitful, to speculate about what may have transpired in 24 hours to induce such a volte-face.

Of a piece with Justice Lau’s observations were the Supreme Court’s orders and observations on the restrictions on the Internet in Kashmir and the indiscriminate imposition of Section 144 delivered on 10 January 2020. Breathing optimism into liberal constitutionalists, the court had observed that access to the internet was protected by the Constitution on a number of grounds and asked the government to review restrictions immediately. It had also held that the imposition of Section 144 could only be justified if the anticipated danger was in the nature of an emergency and could not be used to “suppress the legitimate expression of opinion or grievance or exercise of any democratic right”.

While the Tis Hazari judge took the sting out of the tail of her own observations with a self-contradictory bail order, the Supreme Court order was vitiated by timing. It was not the fault of the bench, but the government had taken good care to ensure that the hearing of the matter had been postponed long enough under the previous pliant chief justice for these observations and orders to remain in the arena of theory.

What the government had wanted to accomplish in Kashmir by way of imposing indefensible constitutional changes through intimidation and occupation, had been accomplished. The matter was heard over five months after Kashmir had gone into lock-down.

These two instances of judicial action point to a creeping de-institutionalisation that is eroding the foundations of liberal democracy in India. It was thought not long back that the Central Bureau of Investigation and other investigative arms of the state could be suborned; statutory bodies or positions like those of the Central Vigilance Commissioner, Comptroller and Auditor General, and even the Election Commission could also be subverted because in the ultimate analysis, the central government held the power to make appointments in all this cases and this power could be misused to ensure partisan compliance. But many citizens thought the judiciary would remain the last redoubt of constitutional governance, notwithstanding the Emergency years.

It is not just these two cases. Just as the Kashmir hearings have been postponed beyond reason, giving the government the space to present the nation with a fait accompli beyond challenge, the hearing of the huge bunch of petitions relating to the CAA and National Register of Citizens (NRC) are being delayed. The first bunch of petitions were admitted on 18 December 2019, but the first hearing has been posted for 22 January 2020. A Supreme Court bench had said on 13 January 2020 that the hearing of the CAA and Article 370 cases would have to wait, because the Sabarimala case, being older, would get precedence.

The CAA case is a matter of fundamental importance because the Act changes the character of the Indian state and is prima facie unconstitutional. The Article 370 case is also fundamental. There is no question here of making a laundry list on the basis of temporal precedence.

Similarly, on 16 December 2019, Chief Justice Sharad A Bobde had refused to hear urgently a petition pertaining to police excesses in Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University, citing reasons that sound flimsy, if not bizarre. He had said, “We are not saying who is responsible, police or students. We are saying rioting must stop. We have enough experience as judges to know how rioting starts and what are protestors’ rights. We cannot decide in this atmosphere. All this rioting must stop. What is this vandalising of public property? We will take cognizance in a cool frame of mind.”

One would have thought that this was a judgment in itself, because the entire point of the Jamia case was that the students who bore the brunt of egregious police action had claimed, and still claim, that they had neither “rioted” nor “vandalised” public property. The people who had done so were the police, which is an established fact, and agents provocateurs instigated either by the government or the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which was a matter that needed to be probed. Which was precisely why an approach had been made to the top court.

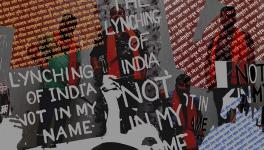

With the independence of the judiciary, too, imperilled, we are looking at the inauguration of a police state, on its way to becoming a full-blown fascist regime. We have seen that with the government’s reaction to peaceful protest in the past month or so. We have seen that with the summary arrests and incarceration of people dissenting from the ruling party’s political ideology, as in the Bhima-Koregaon/Elgar Parishad case. And we have seen that in the repeated use—or misuse—of the sedition law (section 124A of the Indian Penal Code), a colonial-era provision used by the British as an instrument of repression against colonised subjects, which should be repealed by a liberal constitutional state dealing with rights-bearing citizens.

The erosion of institutions has allowed the state to use the full panoply of its powers, especially the “legitimate monopoly” of violence and the possession of the instruments to commit it, in ways that are completely illegitimate. Judicial pronouncements like the ones on “rioting” and “vandalism”, which we have just encountered, create the crucial conditions of impunity enabling state violence and repression, especially since they are seldom balanced by judicial admonition of a regime guilty of misusing its powers.

But we must remind ourselves that fascism is the political expression of a social disease. The question is, what has happened within Indian society that has allowed the current dispensation to slot a liberal democracy into an authoritarian groove. The answers are obviously too complex to be dealt with in this essay, but we have to begin by noting that there is a particular state-society dialectic at work. Indian society is fractured along many lines of divide. The class divide overlays several primordial fractures: along the lines of religion, caste, ethnicity and language. These divisions are always in play and instead of being sealed by capitalism and globalisation, have, in fact, been exacerbated by them in many ways.

The state, with its immense powers, has a role to play in shaping the social formation. What we have seen over the past five years or so is the spectacle of a regime stoking social divisions, sometimes insidiously, often blatantly, to create a climate of jingoistic hysteria and muscular majoritarianism. The latter is encouraged by the party and the regime’s instigation of majoritarian mobs, which undertake vigilante action against the minorities and the marginalised, especially Dalits. The poor of all persuasions also get short shrift. These, in turn, feed the majoritarian and exclusivist designs of the ruling party and the regime. And this dialectic is what is creating conditions for fascism. Even though only around 25% of the people voted for the increasingly fascist and always communally majoritarian BJP.

Luckily “ordinary” citizens are voting with their feet, their time and their energies—at considerable personal cost—to oppose this regime and its designs. We must hope that the 62% of citizens who did not vote for majoritarianism, fascism and a police state win the war that is being fought.

Suhit K Sen is an independent researcher and journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.