Demonising Dissent, Infantilising Society

Image for representational use only.Image Courtesy : Quillette

An international organisation, Humanists International, released a report on 25 June drawing attention to the discrimination and persecution faced by humanists and atheists in eight countries—Colombia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines and Sri Lanka.

Humanists At Risk: Action Report 2020, a kind of appendix to the Freedom of Thought Report, 2019, records testimony from 76 respondents and seeks to add a qualitative flavour to the earlier report, which examined the problem on a broader canvas.

The larger report is an annual feature for the past six years. It tries to track the suppression by states of free thought, rationalism and humanism—as well as minority religious beliefs—to defend religious orthodoxy, deploying the blunt weapon of anti-blasphemy laws or equivalent legislative instruments. It also tracks societal and extra-judicial suppression of minority beliefs, especially those that are not tethered to religion and are critical of and antithetical to religious orthodoxy. Such suppressions are clearly in the territory of human-rights abuse. It also ranks all countries by a number of metrics of tolerance and finds that 110 countries still practise discriminatory funding of religion—56%—including Germany, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom.

India fares poorly on two counts. First, the treatment of minorities, and, second, the constraints it imposes on humanists and rationalists. Other reports have shown that discrimination against and attacks on minorities have grown exponentially ever since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014. The fact that it is now engaged in rolling back the constitutional and institutional safeguards for minorities and dismantling the secular state is beyond contradiction.

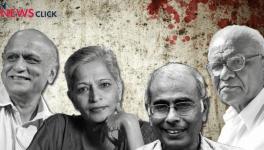

The persecution faced by rationalists and humanists, especially those who disavow any religious belief and campaign against the many forms of intolerance, superstition and obscurantism promoted by religion, especially under a regime guided by a fundamentalist theocratic ideology, receives less attention. The murder by well-funded Hindu extremists/terrorists of rationalists who campaigned against obscurantism and the Hindutva project—Narendra Dabholkar (2013), Govind Pansare (2015), MM Kalburgi (2015) and Gauri Lankesh (2017)—and the continuing failure to bring them to book shines a light on the problem. These murders are, however, indicative of larger problems. The Humanists International report notes: “The existence of vigilante violence is not only indicative of the climate of fear and violence in which some people associated with non-belief are forced to live, but it also points to governmental responsibility in creating an atmosphere conducive to civil violence against non-believers.”

The structural problem is that there is no legal recognition of atheism as a legitimate ideological position that underpins distinct individual and social identities and practice. This is underpinned by social hostility. A decade ago, non-believers just could not record themselves as agnostic or atheist, either in the census or for other official purposes. In other words, people had to declare themselves as followers of some religion, whatever their personal convictions. They were officially/legally and societally/sociologically presumed to belong to the religious group into which, so to speak, they were born.

It was only in the Census 2011 that respondents were allowed to skip religious identification and lumped into an ‘Others’ category. Just 0.27% of the population refused to identify themselves by religion, though they were not necessarily all atheists. A survey conducted in 2006 had 6.6% respondents saying they had no religion. A WIN-Gallup poll found in 2005 that 4% of respondents were atheists and 87% religious. In 2012, another WIN-Gallup study reported that 81% were religious, 13 were not and 3% were atheists.

Given that in absolute terms there must be a large number of people who are non-religious, the state’s refusal to let them identify in such terms constitutes a breach of fundamental rights. Despite a few petitions reaching the courts, Indians are still sought to be compelled to state their religious affiliation in various official and non-official forms (for job applications, admission to educational institutions, etc.).

Whether or not a person identifies with a religion, legally, he or she has no option given the way personal laws and legal codes are framed. This is critically true in matters of property ownership and inheritance, though the Special Marriage Act, 1954, allows non-religious marriages, or “civil unions”, as well as marriages between members of different religions. Push come to shove, however, the legal system shoehorns people into religious categories.

Is this a big deal? It could be argued that categorisation is a trivial matter. It is not, however, given that state-sponsored, legal taxonomies create, and often freeze, identities and thus produce social realities, as scholars of colonial India have shown. The refusal to allow people to identify as being without or opposed to religion is simultaneously a testament to pervasive social intolerance and an instrument to perpetrate intolerance of minority voices that are critical of religion. Many believers would agree that there is a lot to be critical about, without being summarily dismissive.

This brings us to the question of atheism as belief and practice worldwide. Widespread discrimination fuelled in the early years of this millennium a ‘New Atheist’ movement mainly in West Europe and North America, with Richard Dawkins, the former professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University, emerging as one of its most recognisable faces.

Dawkins and others, including journalist and writer Christopher Hitchens, and philosophers Daniel Dennett and Sam Harris, launched a militant movement that was scathingly critical of religion in all its various forms. The high point of this movement was the publication in 2006 of Dawkins’s The God Delusion, a searing excoriation of religion and belief. The book was widely criticised, often with good reason, for taking no account for historical development, sociological realities and human psychology and, therefore, utterly lacking nuance.

This critique while being substantially true ignored the context and objectives of New Atheism. New Atheism began as a reaction against Intelligent Design, the pseudo-scientific theory that attempted to rehabilitate Biblical Creationism as a scientific explanation for the origins of the universe and life. It was especially opposed to attempts by the powerful Christian Right in the United States to mandate the teaching of Intelligent Design as a legitimate scientific alternative to Darwinian natural selection.

In the Global South, for all its ignorance of philosophy and history, the movement does help highlight the suppression of critiques by religious establishments, especially in countries with a massive religious consensus, a powerful religious establishment and weak institutional protections for individual liberty.

In India, not only are atheists denied an identity, they are also made vulnerable to prosecution and persecution by legal provisions that function like anti-blasphemy laws, as Humanists International points out. Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code, for instance, outlaws the expression of opinions that may “outrage the religious feelings” of any group. The report also notes that in many states India’s “cow protection laws” represent de facto blasphemy laws “since people are prevented from eating beef, whatever their faith or lack thereof. There have been multiple reports of people being killed for having allegedly eaten beef.”

Such provisions have such a wide scope that in their attempt to curb hate speech, they end up censoring the fundamental right to freedom of expression. In the context of religion, this disproportionately affects non-believers’ freedoms. In India, where it is ludicrously easy to find people ready to be “outraged”, this also amounts to a blanket censoring of precisely the kind of views that promote dissent and debate, the absence of which is infantilising Indian society.

The author is a freelance journalist and researcher. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.