Writing While Socialist

Mark Nowak: You have facilitated a new series of workshops around India since we last spoke. How has this project evolved over time? What new ideas, techniques, or insights did you bring to the second round?

Vijay Prashad: With each workshop the broad outlines of socialist writing become clear to me. I am now able to better distinguish between capitalist writing—which typically emerges from the liberal, mainstream media and is intended to produce commodities—and socialist writing—which is intended to produce a confident community of struggle. The time in our workshop is spent digging deep to understand how to create these communities.

As socialist writers, we take our lead from the people struggling to improve their worlds.

This leads us to the question of style. It is a myth that style is a bourgeois concern. There is an assumption that socialists are interested in content, not style—in getting the point across in as transparent a manner as possible and not worrying about how a story is framed or what kind of mood it evokes. But the socialist writer is not merely a conduit from the picket line to the reader. The writer must shape the story. It is to encourage discussions of socialist style that I do these workshops in the first place.

Let us consider the Indian state of West Bengal, where the right is currently engaged in a concerted attack on the left. Every day there are new incidents of violence visited upon the working class and peasantry, particularly those amongst them who are communists. Recently the police attacked a demonstration by tea plantation workers, and some of the workers were injured. A writer reporting on the protest has a choice: should one write in the mode of grief, representing the workers as victims, or should one write in the mode of anticipation, conveying the intensity of struggle?

Tea plantation workers on strike in northern West Bengal, 2017. Image courtesy the Communist Part of India (Marxist).

The women protesting in the photograph above should not be taken for victims of a ruthless state. They are not mere spectators to history, they are the ones pushing history forward. The mainstream media does not take them seriously. It avoids telling their stories. It does not question the conditions of their lives and work. It does not ask how they have built up the courage to take to the streets against the more organized and powerful state. As socialist writers, we take our lead from the people struggling to improve their worlds. If we can narrate their struggles with honesty, then we can perhaps bolster their confidence. It is this confidence, and not commodities, that we seek to produce.

It is a myth that style is a bourgeois concern.

MN: I like what you say about the tea plantation workers in West Bengal. This is a discussion we have often had at the Worker Writers School in New York, led by long-time collaborators from Domestic Workers United. The students, who work as nannies, street venders, cab drivers, and retail workers, have seen journalists come in, listen to their stories, learn about their struggle for a domestic workers’ bill of rights, and then disappear. They ask, “Where did my story go?” How do you think workers can maintain some control over their own stories?

VP: Stories travel. That is always a risk. I like Eduardo Galeano’s great line that people are not made of atoms, they are made of stories.

Imagine a journalist at a protest, watching people march and chant but unable to comprehend them as anything but quaint or anachronistic. This is a journalist who sees the event—the meeting or the protest—but cannot see the process, cannot see the history of struggle. What use is this journalist’s story to the workers? Will there be anything but condescension in the prose? The workers won’t recognize themselves in the story. There are the liberal writers who approach workers with sympathy. They see them as victims, as people to be pitied for the terrible conditions of their life and work. Such writers want their readers to recognize the existence of injustice, but again only as an event—something to look at and bemoan. The intention behind such writing is to provoke the readers to act on behalf of the workers. In this setup, the workers are to be pitied, they are not seen as drivers of human history. Others have to act for them. No wonder there is little in their texts that workers can recognize. These victims are alien to them.

One of the ways in which workers are written out of the news and out of history books is that their lives are not seen as producing history. The mundane nature of working-class and peasant life is seen as reproductive, not generative—merely reproducing the world but not making new worlds. But history is produced by the sentiments of the workers and by their struggles. Attention to their everyday lives allows us to better understand extraordinary developments, which build off millions of small gestures made by ordinary people.

Socialist writing is intended to produce a confident community of struggle.

I recommend that people visit the People’s Archive of Rural India, a website that documents the lives of rural Indians, driven by the ferociously energetic and brilliant journalist P. Sainath. Nilanjana Nandy’s story about women who fought to sit on chairs in Rajasthan and Parth M.N.’s story about borewells in Maharashtra are good examples of socialist writing. Sitting on a chair is not only about sitting on a chair. It is about the increased confidence of women in rural India. Where this confidence goes is the next chapter in the story.

Left: Babli Devi, Kharveda village; Right: Sangeeta Bunkar, Kharveda village. Image courtesy the People's Archive of Rural India.

These small voices of history are the pebbles thrown into a pond that set in motion the cascading waves of history. Such stories are not taken seriously by mainstream writers, but a socialist writer must make them central. They are, after all, signs of confidence that lead from everyday life to extraordinary events. They are what workers, as readers, can recognize as real stories of their lives and struggles.

MN: So the liberal writer hopes to engage the reader to act on behalf of the struggling, downtrodden subject while the socialist writer hopes to document their subjects engaged in acts, minute and major, of resistance? How would you relate this in one of your workshops? Could you walk readers through one of your recent workshops to help us understand how you practice this in your pedagogy?

VP: There is a major political distinction between the liberal writer and the socialist writer. The socialist writer, to my mind, must believe that change is possible. This does not mean that such change is inevitable, merely that it is possible. Cynicism and pessimism are not the mood of the socialist. This means that when injustice is uncovered, the writer assumes that justice is possible. Perhaps the antidote to cynicism is to retain faith in the capacity of human beings to overcome the present. For this it is important to treat the people that one interviews not merely as repositories of information, but also as reservoirs of hope and anticipation.

Workers are not mere spectators to history, they are the ones pushing it forward.

What kind of hopefulness do people exude not only in their words, but also in their practice? PARI published a story about a man, Karimul Haque, who works in the hills of West Bengal. His mother died because there was no ambulance available to her when she needed one. Subsequently this man has turned his motorcycle into a kind of ambulance. He now ferries people across the hills to local hospitals. In another story, Srilal Sahani, who lives just down these same hills and is in terrible debt, spends his mornings selling fish in the local market. In the afternoons, he rides his bicycle up and down the main street, beating on a small drum and singing songs. Both men are gesturing to life beyond the misery of the present. They have taken history into their own hands by attempting to improve the lives of the people around them. These may seem like small gestures, but they are significant to those whose lives have been impacted. Karimul Haque is saying to his neighbors that they need not to wait for an NGO to come to their aid, that they can make their own history. Srilal Sahani won't allow debt to define him. In both these stories hope is not a theoretical concept, it is real and palpable. A writer who abandons hope is abandoning the stories of these people. These may be stories of survival and not of political transformation. But stories of survival are the first drafts of revolutionary action. In our time, we must write stories that are both about incubated revolutionary sentiment—such as those of Karimul Haque and Srilal Sahani—and stories of protest.

In a recent piece, Viet Thanh Nguyen points out that writing workshops are often hostile to politics. Aside from the art of writing, he notes, these workshops “did not have anything to say about the matters that concerned me: politics, history, theory, philosophy, ideology.” This was not a problem in our workshops across India, where we took art and politics as equally important and indeed intertwined.

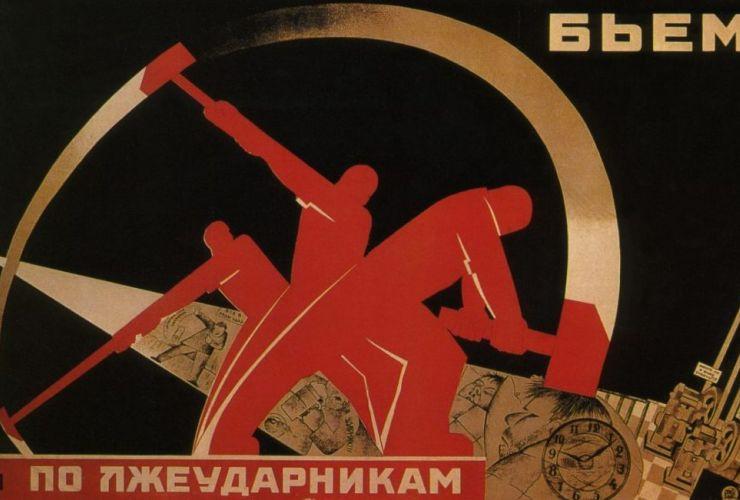

One example is our emphasis on “smashing language.” We drew up lists of hollow or dead words: development, freedom, growth, and sustainability. Having made this list, we then “smashed” the words, broke them up in order to awaken the meaning within them. The example I give my students is from the first few months after the Russian Revolution. The Bolshevik leader Krupskaya recounts the “altered language” she heard from women workers and peasants in a meeting. The speakers, she recounted, “spoke boldly and frankly about everything.” Their language had changed. Communist futurist writers, such as Mayakovsky, drew from what they saw in these meetings. They had to “smash” their language to bring it back to life. The assumption was that the old Russian language was saturated with feudal implications. It could not be inherited without first being “smashed.” So in the workshop we do what Mayakovsky did to language, we plunder and pulverize it, playing games with the words.

You can well imagine what people do with words like development and freedom—how they play around with them until the words become meaningless and perhaps even imbued with new meaning. The emergence of new words shows how hope is embedded in our own fierce desire for a better world. It reaffirms the belief that we are not trapped as long as we are able to conjure, if only in language, an alternative world. In Homage to Catalonia, George Orwell reflects on the changes he witnesses in Barcelona. He writes: “There was much in this that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.” It is this attitude that our workshops hope to cultivate.

Change is possible. We are not trapped as long as we can conjure, if only in language, an alternative world.

MN: You mention Eduardo Galeano above. He is perhaps my favorite writer. In the past you have also talked about James Baldwin. Galeano and Baldwin are two writers who try to construct a bridge between socialist writing and literature, who borrow from both traditions to sketch extraordinary exposés of struggle and resistance. Are there other writers that clarify your conception of socialist writing?

VP: Baldwin is so important. Make language “clean as a bone,” he advised. I take that advice fully. There are many writers I admire for what they do with the stories around us. I have already mentioned the journalist P. Sainath, with whom I co-taught a workshop. He is really one of the finest socialist writers today. I would also like to encourage people to read the work of Brinda Karat, one of the leaders of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). She spends a great deal of time traveling around India, interacting with workers and peasants who suffer and struggle. What I find most interesting in her writing is that she conveys the hardships that people face as well as the determination to overcome their conditions in equal part. In a recent column, she documented the assault and murder of a young Muslim boy, Junaid Khan, on a train in northern India. The story begins with a portrait of Junaid’s mother, Sayara, mourning her son, then documents the murder and the underlying Hindutva politics that caused it, and concludes with a call to arms against the suffocation of public space. Karat's writing evokes pathos and rage, but also complicity. It reminds us that nobody helped Junaid, and that our collective silence is what killed the boy.

Ryszard Kapuściński's ability to write about politics is almost magical. There are stories that he fabricated some of his experiences in Africa, and that is unforgivable. But there is an object lesson in the way he was able to bring his readers from Poland into worlds that they knew little about, to teach them about power and culture and to encourage them to puncture their parochial visions and take in the world. We forget that he was writing in Polish and was telling the stories of Iran and Ethiopia to people in Warsaw and Szczecin. There are many heirs to Kapuściński: such as the Colombian writer Santiago Gamboa and the Lebanese writer Sahar Mandour. They are novelists and journalists of the left, writing in Spanish and Arabic respectively, and telling stories of intimate worlds that have the capacity to explode into something dynamic and deliberate. You cannot have socialist writing today that does not engage with private, domestic worlds alongside the world of the streets. The latter is not enough.

MN: Speaking of hope, in recent years we have seen the rise of so many new social movements and so many energized, young activists participating in Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, the Bernie Sanders campaign, #NoDAPL, protests against the “Muslim Ban,” and other anti-Trump protests. What writing advice would you give to people becoming politically active, some of the first time, in this moment? There seems to be an imbalance between the speed needed by today's technologies, such as Twitter, Facebook, and live-streaming, and the necessity of pausing and thinking about how to tell the story. How do we, as emerging writers in social movements, achieve any balance between the two completely different paces of our writing practice?

Stories of survival are the first drafts of revolutionary action.

VP: The difference between Twitter and long-form writing is in the length of the text, not in the thinking that goes to produce it. One could produce a thoughtless long-form essay as easily as a thoughtless tweet. To me the length or the speed of production is not the issue. What is at stake is the understanding behind what one is writing. If one does not have a good way to explain these protests, one will struggle to report them either in a tweet or in a book. A socialist writer who wants to track these movements needs to take a step back and look at the historical dynamic of these struggles, where they come from and where they could potentially go, what stands in opposition to them, the closeness or distance of these movements from the people, and the question of whether the demands being articulated can speak to the lived anxieties of people. These elements—if answered with care and close study—will help the writer understand how to write about something, whether in 140 characters or in 500 pages.

Both those on the inside and those on the outside of movements would be well-served not only by accounts of what is happening, but also by accounts that provide the broader context. Our movements are born out of older movements, older uprisings that produce our confidence, and our movements in turn birth new and, we hope, broader revolts against the present order. That is the kind of historical sweep that socialist writers need to create. Their job is not simply to define the terms of an event, thereby rendering it mythical and impossible to replicate. The reader must not think, “I wish I was there.” The reader should think, “I was not there, but I’ll be there tomorrow.” The story has not ended, it is ongoing. Engels wrote that history moves “often in leaps and bounds and in a zigzag line.” It does not necessarily move in a progressive direction, and can just as often fall backwards. A story needs to represent that: the journey from and the journey towards.

Arthur Rimbaud called a good poet a “thief of fire.” That is a lovely phrase. There is despair for humanity right now, but there is also optimism. That’s what our socialist writers must strive for—to be thieves of fire.

Editor's Note: Over the past year, the scholar and activist Vijay Prashad taught a series of nonfiction writing workshops to students, activists, workers, and journalists across India. The workshops sought to develop an ethics and practice of socialist writing to foreground what Prashad calls “the small voices of history.” Here he talks to the poet Mark Nowak, founder of the Worker Writers School in New York City, about the political valence of socialist writing in a time of rampant populism, racism, and xenophobia. This is the second in a series of dialogues between Prashad and Nowak. Their first conversation, The Essentials in Socialist Writing, was published in Jacobin.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.