Wither the Middle Class?

Even as India struggles to regain its growth momentum, let alone provide jobs to tens of thousands of people entering the market for work every day, there are fundamental changes taking place in labour markets around the world. And there are important lessons for us here. Most importantly, even if growth creates jobs it may not be accompanied with rising wages so that while inflation may remain in check, expected improvements in standards of living for the working class may not be realized, and at the same time, inequalities of income and wealth may worsen over time. The present primacy allotted to GDP growth in India may therefore not suffice to ensure development and betterment (absolute and relative) in living standards for a vast majority of its population.

Global boom

2016 was a significant year for the global economy; for the first time since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-2008 most advanced countries of the world including the USA, Canada, UK, Japan as well as the European Union showed signs of a sustained recovery in not just real GDP growth but also in terms of lower unemployment rates as well as low inflation. Stock markets were buoyant, private sector investment began picking up, factory/industrial output was strong. This trend seems robust; the 2018 World Economic Outlook report projects“that advanced economies as a group will continue to expand above their potential growth rates this year and next before decelerating …” Isn’t this what economists call a Goldilocks period?

Read More: The Gathering Storm Clouds

Standard macroeconomic models would, however, begin to see a problem developing in such situations that would decelerate growth rates. As unemployment rates fall and approach the “natural rate of unemployment”, shortages in labour markets would trigger a rise in wages that could set off a wage-price spiral. This would then induce monetary policy interventions through higher interest rates to dampen private sector investment and consumption demand thereby containing inflation to low and stable levels.

Low inflation, low wage growth

However, things are not quite working out in textbook fashion with concerns developing in these countries over the behaviour of some economic parameters. Foremost amongst them is the subdued response of inflation rates to accelerating growth and employment. The US Fed is tentative over interest rate hikes simply because inflation has remained unusually low in spite of definite signs of a recovery in growth and employment. Looking ahead, longer term inflation forecasts for the US over the next two to five years remain close to the inflation target of 2.1% while other advanced nations struggle to reach their target inflation rates of +2%.

Read More: Mr. Jaitley’s Delusions About Jobs

One reason for this high growth, low unemployment and low inflation combination is to be found in the labour market. In most of the above countries, annual real wage growth has remained low and much lower than the increments witnessed pre-GFC. However, before jumping to conclusions on the plight of labour, it is important to understand that real wages must also increase in sync with productivity increases. If the changes in real wages are greater than the latter it means that the share of labour in the national income is actually improving. And this could indeed be the case in the US. As one commentator questioned in contrast to most others; why was US nominal wage growth so high at 2.4% when productivity growth was 0.6% and inflation at 1.4%? If so, what then is the actual cause for concern in this trend of low real wage growth?

The productivity paradox

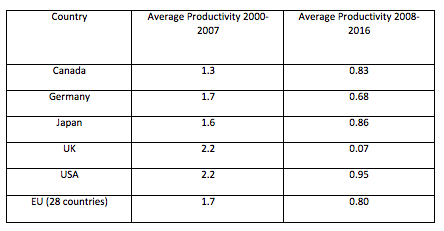

The answer is productivity growth. Table 2 below has been constructed from OECD.Stat database for select countries where productivity is measured as GDP per hour worked, constant prices. Average productivity has been computed for two time periods, namely, 2000-2007 and 2008-2016.

Table: Productivity decline in select advanced countries/regions, 2000-2016

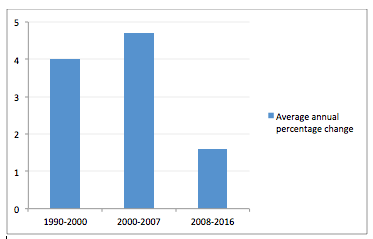

As evident from Chart 1, productivity changes in the US manufacturing sector between 1990 and 2016 were even more alarming. This significant secular decline in productivity across sectors in the advanced world post-GFC is paradoxical. In fact, Robert Solow had raised this in 1987 when he remarked, “you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

Chart 1: Productivity change in the US manufacturing sector, 1990-2016

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Productivity growth or output per worker per hour is critical for longer-term improvements in standards of living. When we produce a greater quantity of output from a given number of working hours, we are able to enjoy the additional fruits of our labour but can also choose in favour of increased amount of leisure time. Stagnation in productivity would mean stagnation in standards of living. Productivity growth is propelled by investment in capital goods, technological change and improved management practices. The benefits of these changes may not be realized in the immediate future but with lags over the longer-run; this could have been an underlying reason for the Solow Paradox. However, the gains from improved productivity may dissipate gradually until new technological shocks once again trigger a productivity cycle. The GFC of 2007-2008 deeply impacted private sector investment spending, which may be the reason for the declining productivity growth observed. Another compelling argument comes from supporters of market forces; increased anti-competitive regulation, subsidies, low interest rates have allowed low-productivity firms to survive the competition from high-productivity ones. On the other hand, there are economists who think that it is the move towards financialization of the economy, rather than government and private real investment in infrastructure, science research and R&D, which is resulting in the insubstantial productivity trends.

The gig economy

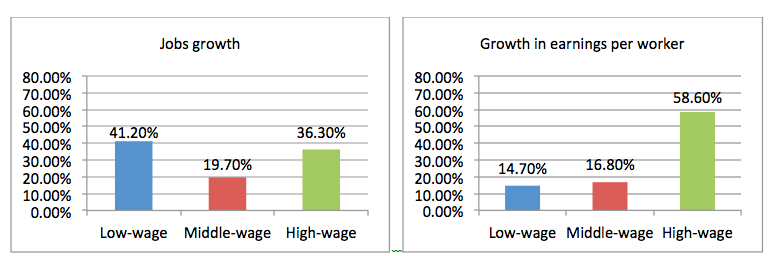

While these reasons are not conclusive, there is another perspective that is fuelling a debate on the reasons for low productivity and low wage rate growth: the gig economy where work is essentially piece-work, by task, flexible and independent. This autonomy, however, comes at a cost to the worker which includes absence of trade unions, job insecurity and lack of health, insurance or retirement benefits. The gig economy has proliferated because of digital platforms and Internet technologies. Although one may hastily jump to the conclusion that workers are exploited, the McKinsey Global Institute found that while independent work accounts for 20-30% of the working age population in the US and EU (15 countries), almost 70% have opted for it as the preferred choice, only 30% do it out of necessity. While not all workers in the gig economy earn low wages, the worry is that more than 50% of most low-wage households engage in such work. The post-GFC rise in unemployment made the market for independent workers extremely competitive, driving down wages. Employers like Uber and delivery couriers are also able to equate their marginal revenues and marginal costs continuously. Workers know this and without any bargaining power whatsoever, fear asking for higher wages. Although low unemployment figures are good news, jobs are getting more polarized. At one extreme, there are the highly-skilled workers earning high real wages while at the other extreme there is a growing proportion of low-paid workers, many of whom must now find employment in the gig economy. Obviously, the average real wage seems fine but in reality the “middle-class worker” with good, old-fashioned and secure jobs is fast-shrinking. Chart 2 graphically illustrates this emerging predicament in the US labor market.

Chart 2: Growth in jobs and earnings by wage levels in the US, 1990-2015

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Woods & Poole Economics, Inc., PERE National Equity Axis

The effects of the gig economy and increasing proportion of low-wage workers on productivity are still ambiguous; while self-motivation may enhance productivity, the flexibility offered by low-wage independent workers may incentivize firms to postpone or shift away from productivity-enhancing capital investment. The impact of these changes is still not clear but there is no doubt that labour markets in advanced countries are moving towards greater flexibility and polarization at the extremes rather than expansion of middle-class workers.

Lessons for India

India and many other developing countries are not exempt from this phenomenon of low productivity growth. Along with stagnation in agricultural productivity, India must also contend with the chronic slowdown in private sector corporate investment spending in recent years. While, automation in the manufacturing sector will see the need for more highly skilled workers with high wages, the signs of a low-wage gig economy are visibly manifesting itself in urban centers. The vision of India creating adequate jobs in the organized sector and building a strong middle-class (like the advanced world managed to in the second half of the twentieth century) by moving on to a higher growth trajectory seems increasingly problematic given the recent trends emerging in the developed world. To the contrary, the polarization of the working class and widening inequalities in spite of high growth may well be the unfolding reality.

Also Read: 200th Anniversary : Marx And Capitalism

Sashi Sivramkrishna is the author of the book, In Search of Stability: Economics of Money, History of the Rupee, Manohar, New Delhi 2015.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.