Why Dalit-Bahujan Icons of Cultural Resistance are Under Attack

The song “Aya Desh Bikreta” recently went viral on social media. It garnered millions of views on YouTube channels and got so popular during the recent Bihar election campaign that many started referring to it as an anthem of political Opposition. Central to this song is a strong critique of privatisation—which Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s regime has been frantically encouraging—and how it has compromised the interests of people.

However, responses to the critique of privatisation were also virulent. The artists, Vishal and Sapna, received life-threats from online trolls. Vishal’s studio was gutted, and in many interviews and videos, both artists complained that casteist slurs are being constantly hurled at them. They have also filed a police complaint, invoking provisions of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 against some offenders.

Yet, there is another development, disturbing and ironic in equal parts: Recently, Vishal and Sapna were arrested by the Uttar Pradesh Police for having joined a sit-in protest.

Now, critiques of privatisation are not new to the discourse in any part of India. The popular press and non-mainstream media have often engaged with the privatisation of public sector units. In fact, there have been constant public debates on this subject for decades, led by a range of media platforms arguing all sides of the issue. What is intriguing in the case of Sapna and Vishal is that their critique of public policy has met with a blend of casteism, via the troll armies, along with the repression of the ideas they invoked by the State.

As Dalit-Bahujan singers, Sapna and Vishal are certainly not novices to songs of resistance. Their discography includes Ambedkar mission songs such as “Aei Bheem Diwano Chalo”, “Yudh Nahi Budh Chahiye”, “Shan se Bolo Jai-Jai Bhim,” and many others. If particular attention is paid to their content and form, their songs create a language to resist oppressive caste structures and other iniquities. From their singing style to the snippets from history they present, to their invocation of Dalit-Bahujan icons, they foster a unique anti-caste narrative. The “controversial” song, “Aya Desh Bikreta” (which translates to “Here Comes the Seller of the Nation”) also begins with a historical snippet. It refers to Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya empire in ancient India, who was a political and economic reformer and ruled over one of the largest empires. Due to the expanse of his empire, Chandragupta is often called a “unifier” of India. However, in the right-wing nationalistic discourse, all ideas of unified India are secondary to the notion of Hindutva, which aims to unite caste-Hindus against a common enemy, the minorities, and which seeks to reinforce the traditional caste-varna hierarchy. For this reason, outfits that support the current regime also make it their primary goal to drown out all dissent, especially the voices of Dalit-Bahujans.

What music means to Dalit-Bahujan communities

Music is more than aesthetics or a source of momentary transcendence or reclusive distancing. It is also their language of resistance, deeply rooted in their reclaiming and recasting their identity. Thus, music is an important means to establish a counterpublics for Dalit-Bahujan communities. It is through songs and music that they have developed an anti-caste narrative.

Such resistance is rooted in their social movements, that have reclaimed the public sphere for Dalit-Bahujan dignity. In Maharashtra, Sambhaji Bhagat created songs of resistance in the musical practices of Ambedkari Jalsa which honours Dalit-Bahujan icons. His performances are a popular element at culturally significant occasions of the community. Similar efforts to reclaim cultural spaces are being made by groups such as Casteless Collective, a Chennai-based Tamil-Indie band started by Pa. Ranjith.

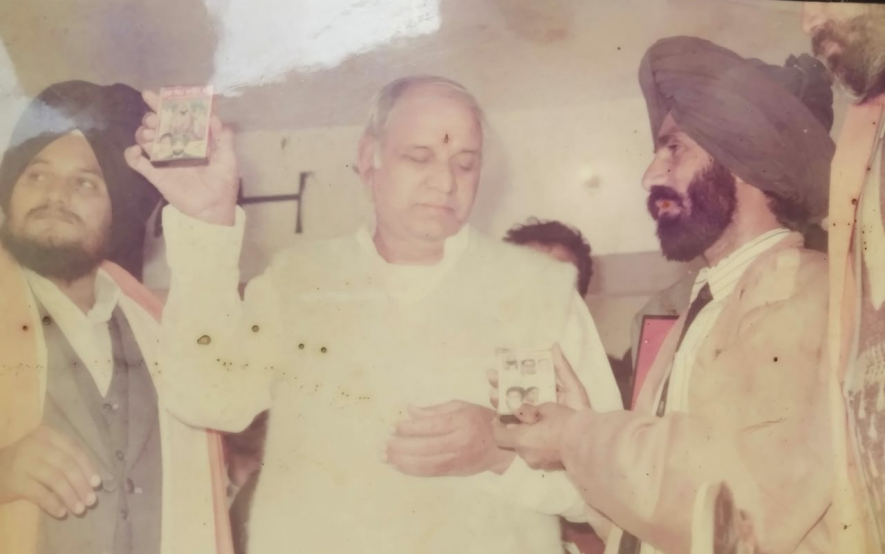

In North India, independent performers and anti-caste cultural groups, such as Youth for Buddhist India started by the late Shanti Swaroop Baudh, engage in musical practice and performances as a form of cultural resistance. The practice goes back to Kanshiram, founder of the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Dalit Shoshit Samaj Sangharsh Samiti (DS4). DS4 brought together singers in a number of languages and regions. They struggled for an anti-caste discourse that gave a socio-political voice and dignity to Dalit-Bahujans.

Kanshiram releasing the album of DS4 singer Harnam Singh Bahelpuri in Punjab.

Over time, folk practices and popular genres of music in North India changed in form and content. Folk genres such as Birha, Ragini, Alha and Larichand began to occupy political spaces too, which in itself was a revolution for it marked the break for what was largely cultural into a non-conventional realm. The changes in musical practice reflected the new socio-political claims that Dalit-Bahujan communities were making. These cultural spaces were particularly important for women, who were active participants at community events.

This social history of musical practices is important as it reflects what cultural artifacts mean to Dalit-Bahujans. Their musical practices give them a sense of calm, in which they position their identity and dignity.

Dissent? Or Culture?

Cultural theorist Stuart Hall has argued that culture is a contested space, not a fixed entity. Rather, it reflects the process of “becoming”. Dalit-Bahujan culture is often subsumed within “mainstream” culture or passed over, forgotten. Therefore, their musical tradition becomes inherent to the anti-caste social consciousness. From Dalit Panthers to DS4, it puts their displaced narratives at the centre again.

Dissent cannot be downplayed as a feature of cultural performances, yet there is a need to contextualise this dissent. The dissent in Dalit-Bahujan songs is a claim to alternative spaces that provide a narrative to their untold histories. For instance, Bhimgeet or Mission Songs often emphasise on giving history a context. Consider the popular folk genre of Alha-Udal, a musical practice that is popular in the Faizabad region of Uttar Pradesh. This practice involves story-telling, and the preferred theme is narrating the biographies of icons. In an Alha, as a narrative technique, even the minutest details of icons are discussed with utmost precision. As the anti-caste movement gathers steam in this region, the traditional Alha-Udal form of singing is being replaced with Alha singing on Babasaheb Ambedkar and Kanshiram. This shift is a form of dissent against the hegemonic cultural practices that eclipse Dalit-Bahujan history.

Cultural dissent and saffronisation

With the arrest of a Vishal Ghazipuri and Sapna Baudh, cultural dissent seems to have no easy road ahead. However, this is not the first time that a Dalit-Bahujan dissent has been meted high-handed treatment by a Brahmanical state. Even in the early 1980s, DS4 singers confronted casteist slurs during public performances.

Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar wrote in “Revolution and Counter-Revolution” that ancient history experienced the revolutionary impulse when Buddhism emerged and rejected the vices of Brahmanical society. However, this revolution was squashed by staunchly Brahmanical forces. In contemporary times, that epoch of history seems to be repeating itself, just under a new banner of saffronisation.

Unfortunately, today cultural assertion and dissent are being reduced to “sedition” and subjected to troll armies and threats. The irony is that while the votaries of saffronisation claim they are building “Akhand Bharat”, in that imagination, the claims to their own history and cultural heritage by Dalit-Bahujans are ignored or penalised. Today, the Brahmanical forces are breeding hatred towards dissenting voices, even of those who have been historically exiled to the peripheries of society.

Kalyani is a PhD scholar at the Center for the Study of Social Systems, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.