Why Chennai-style Rainwater Harvesting Doesn’t Work

‘The location of the English settlement of 1639 cannot therefore be described from the health point as anything but a blind one that has resulted in a perpetual groping for water which has not yet found its goal.’ This statement, from The Problem of Water in Madras, an article published in 1938 as part of the Madras Tercentenary Commemoration volume, still rings true in 2019.

Chennai has six sources of water, but it continues to grope for supply adequate to meet its needs. Things have come to such as pass that it is now exploring the use and reuse of both potable and non-potable water at an unprecedented magnitude.

At present, Chennai depends on the Chembarambakkam, Poondi, Puzhal and Cholavaram water reservoirs situated on its outskirts. These draw water from the two major peninsular rivers, Krishna and Cauvery, via the Telugu Ganga project and Veeranam Lake scheme respectively. Chennai also has desalination facilities along its coastline.

Then it has a loosely-organised, private tanker lorry industry, which mediates water distribution and packaged drinking water supply to the city. They source their water from abandoned rock quarries, from groundwater pulled up through wells and bore-wells in the city and from agricultural bore-wells in neighbouring districts.

Despite all these sources of water Chennai city is failing to meet its growing needs. Here we explore the possibility and potential of one much-vaunted source: rainwater harvesting. This source is being considered as the seventh source of water for Chennai in future.

WATER AND CHENNAI: AN OVERVIEW

A salient feature of Chennai’s meteorological history is its failed monsoons. As the city expands and its population burgeons, the demand for water has outstripped supply. As a result, a non-convergent trajectory of the two—demand and supply of water—has emerged.

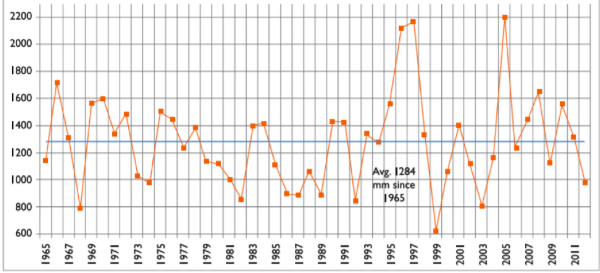

Figure: Annual Rainfall in Chennai (in mm)

In the post-independence era, Chennai experienced a water supply crisis at least once every decade caused by a lull in monsoons. This crisis was most notable in 1968, 1973, 1986 and in 1993-94.

Though in line with this trend, in 2002, 2003 and 2004 came the unprecedented consecutive failures of monsoons, which led to an even deeper water crisis. The crescendo of water shortages was reached in 2003-04. This was happening to a city in which monsoons had failed in 1999 and 2000, already stressing the city’s water supply and deeply afflicting its residents.

In 1968, Chennai had experienced another water crisis after which the Veeranam Tank project was announced. It envisaged drawing water from River Cauvery to feed the Veeranam Tank, 225 km south of Chennai. This was the city’s first proposed project, which relied on drawing water from a river basin not connected to the city. That said, Veeranam Tank project only became operational 35 years later, in 2003, when the city’s water crisis peaked.

Next, in 1976, the Telugu Ganga project was proposed wherein waters would be drawn from River Krishna in Andhra Pradesh to supply water to Chennai. This project was also initiated after a long wait, in 1983 and it was completed another 15 years later, in 1997.

This excerpt from a letter written in August 2004 by the then Tamil Nadu Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa describes the city’s strong dependence on various water sources, including Veeranam and Telugu Ganga:

“In January 2004, out of the total supply of 175 million litres (MLD) per day, the contribution of neighbouring groundwater wells was 140 MLD, and that of the reservoirs 35 MLD. Now [in August 2004], despite the fact that the reservoirs have gone dry, the daily supply has been stepped up to 205 MLD. This... has become possible only because of the supply from the New Veeranam Project, which contributes 75 MLD.

There is a misconception that the City Water Supply is being maintained today wholly by groundwater from wells around the city. It needs to be emphasised that today the city’s water supply at 205 MLD is substantially supported by 75 MLD received through the New Veeranam Project pipeline. Had this project not been commissioned, Chennai would have had to live with less than 130 MLD, meaning extreme water shortages. This will be stepped up to 180 MLD when the Veeranam Lake receives fresh supplies in the ensuing North East Monsoon season”.

To contextualise this further, Chennai receives 60% of its rainfall via the North-East Monsoon (October-December) and just over 30% of its rainfall from the South-West Monsoon (June-September). But, in 2004, there was a 32% deficit in the North-East Monsoon.

Moreover, the two pipeline projects, Veeranam Tank and Telugu Ganga, were and continue to be marred by uncertainty. Chennai’s water security rests on these rivers but their flow ebbs and tides based on political maneuvers.

To top Chennai’s worries, its dependence on groundwater discharge from aquifer (groundwater) hit a roadblock when it was observed that salt-water intrusion had taken place into it. A 2017 study of Chennai district’s aquifer system by the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) says that the city’s groundwater aquifer was “over-exploited”. As a result, seawater had intruded up to 16 kilometres inland in some areas. The report also underlines the excessive use of groundwater aquifers in neighbouring districts to cater to the needs of Chennai city. Thus, even the groundwater around Chennai was close to over-exploited.

The CGWB report recommended desalination and augmentation of surface water during the flood season. It also recommended artificially recharging the aquifer based on the finding that natural recharge by rainfall would be insufficient to recoup groundwater, considering the extent of its extraction.

While dependence on groundwater is unavoidable in large cities, Chennai in particular, in the mid-2000s the state government considered the desalination option. Considering the large scale at which this intervention would have to work, the city incorporated the Chennai Water Desalination Limited (CDWL) to manage it in August 2005.

To complement its work, rainwater harvesting—at the level of individual efforts by citizens—was also set into motion. Among other things, this involved the construction of structures to recharge wells and bore-wells with the rain that falls on rooftops and within land plots. In this way both individual houses and housing complexes came under its purview.

A TIMELINE OF ATTEMPTS TO REGULATE GROUNDWATER

After a below-normal monsoon in 1986, The Madras Metropolitan Area Groundwater (Regulation) Act was passed in 1987 to regulate and control the extraction, use and transportation of ground water. It sought to conserve groundwater in Madras (Chennai) and some revenue villages of the nearby district of Chengalpet (Chengalpattu).

The Act also provides a glimpse into how the city had exhausted all other possibilities to augment its water supply. It mulled over a scheme to artificially recharge the Arni-Korteliyar basin with the excess flood water that was then flowing into the sea. It proposed inter-linking the Arni and Korteliyar rivers and constructing check dams along Korteliyar so that the groundwater is recharged as well. This step was also seen to form a hydraulic barrier against seawater intrusion—a problem the city still faces today.

While the Act mentioned the circumstances which necessitated aquifer recharge, a statutory approach of redressal was adopted only seven years later in 1994. This coincided with the water-stressed conditions in Madras in 1993-94 due to the failed 1992 monsoon. The Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA) and the Corporation of Chennai now began issuing permissions to construct any building only if they first incorporated a rainwater harvesting system in their proposal.

Next, in October 2002, during the start of the North-East Monsoon, the 1987 Act was amended to make rainwater harvesting compulsory in all buildings in the state. In 2002, the rainfall in Chennai was 17% above the normal for the October to December period. Despite such ripe circumstances for harvesting rainwater, the amendment did not prove effective due to the lack of time to put necessary structures in place for harvesting.

In the subsequent year (19 July 2003), the state governor promulgated an ordinance well before the onset of North East Monsoon, making it mandatory for all buildings to construct rainwater harvesting structures such as a collection tank or bore-well recharge, before the monsoon arrived. Moreover, the ordinance also spelt out penalty provisions to check cases of non-adherence.

WHO MONITORS, EVALUATES AND ENFORCECS RAINWATER HARVESTING STRUCTURES?

After this ordinance, a flurry of rainwater harvesting structures were erected by building- and individual homeowners. The owners preferred well-based rainwater recharge structures over collection tanks or sumps. With consistent pro-harvesting campaigns initiated with a well-publicised inauguration of a ‘Rain Centre’ in 2002, several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) started communicating the need for rainwater harvesting to people as well.

As a result, there was a construction spree in 2003-04. House owners erected rainwater harvesting structures across the city. However, they mostly sought to create structures that satisfied the minimal requirements of the ordinance. From the subsequent year on, the construction waned, especially after the Chennai deluge of 2005.

Further, anecdotal evidence indicates that a bulk of these rainwater harvesting structures went defunct. This was partly due to their lack of upkeep after the floods and partly due to relatively above average monsoons in Chennai. Better rains led to a creeping erasure of memories of the early 2000’s water shortages.

In addition, in the post-2005 period, small entrepreneurs began supplying Reverse Osmosis (RO) treated drinking water to middle and lower middle-class families in Chennai. This reduced the dependence on Chennai Metro Water Supply and Sewage Board-supplied drinking water. Furthermore, the emergence of private tanker lorries supplying water to apartments and office complexes eased the situation and accelerated the forgetting of days when Chennai had been desperate for water.

This brings us to the long unanswered question: why was rainwater harvesting positioned by the government and NGOs as a low-cost, commonsense solution to rejuvenate the groundwater aquifers of Chennai? Governments insist on ‘individual action’ which is by very nature marked by uncertainty. Similarly, the results of individual action also depend on human behavior and at best deliver average results.

BEYOND INDIVIDUAL ACTION

The discourse around rainwater harvesting in Chennai revolves around consistent efforts to evoke a sense of altruism. It encourages people to contribute to the “unseen” common pool of water beneath their homes by constructing harvesting structures. However, there is no credible information at hand in terms of the nature of aquifer that people are drawing water from or the geology of the region they are in.

Moreover, the effectiveness of the frugal structures built by owners in recharging this ‘unseen’ common pool is questionable. Despite these limitations, the idea that they are being altruistic continues to be central to the ‘mission’ of redressing the water problem the city confronts. Further, credible reports on how much these recharge structures actually contribute to groundwater rejuvenation are not available.

That said, on the positive side, the sustained campaign around increasing awareness has resulted in dissemination of talking points among people in Chennai and fostered a conspicuous sense of duty and responsibility towards the issue. Rainwater harvesting has now assumed a life of its own in the city. The practice is getting bundled with antiquity in general and with new-age environmentalism tinged with streaks of historical revivalism and European-style green politics.

As a matter of fact, people have already done their bit at their individual level. The next step is to take this forward by bringing the geologists, hydrologists, architects, well-diggers and masons together in Chennai. This is required in order to enable an ecosystem to emerge that can provide a meaningful direction to a campaign that has been raging for the last 17 years.

Campaigns like ‘A Million Recharge Wells’ in Bengaluru provide a template towards capacity-building. It draws not just from traditional knowledge and skills but also from the community in order to nudge an ecosystem that can solve the groundwater depletion issue into place.

Seen in this light, the science of rainwater harvesting demands a more vibrant discourse. It is being pitched as an initiative centered around individual action alone, whereas an unwieldy problem like water scarcity requires techno-managerial solutions. In such a solution the science assumes greater importance.

Put simply, the methods adopted for harvesting rainwater need to factor in the particular nature of the environment they are being created in and what that environment needs. Importantly, the role of government needs to evolve towards investing in projects which have economies of scale and are therefore a lot more productive than isolated individual efforts.

In the latter, limitations stem from the transient nature of people’s memories of scarcity and from the fact that perceptions of the nature of groundwater as a resource vary from individual to individual. Therefore, it is imperative for the government to lead the redressal process through investments and by invoking a sense of collective action. This step would capitalise on the awareness that has already been created at the level of individuals in the best possible manner. Follow-up questions on the promotion of rainwater harvesting are needed: who would monitor the construction of these structures, who would evaluate their efficacy and what would the nature of enforcement be?

The Swachch Bharat Abhiyan has given us an idea of the limits of force in the context of capacity-addition via individual action and, importantly, of the sustained use of the capacity that is being individually created. At this juncture, it would help if the government rethinks its rainwater harvesting strategy.

Rainwater harvesting as a technological intervention via policy decision is tailor-made for governments to meaningfully engage citizens and for them to develop a sense of being a part of coping with challenges that require a collective resolve. Thus, it is equally important to clear the haze around how appropriate the solution is, given the time, money and effort that various stakeholders have put in this.

The groundwater situation is far from being diagnosed. It requires an ecosystem to emerge that taps the power of large collective structures as against only small individual structures. If such an approach is adopted, it would imply that the stakeholders will at the least get a real sense of the risk that the city faces and at best the required aptitude towards managing it.

Jeyannathann Karunanithi is a biochemical engineer based in Chennai. Vignesh is a doctoral researcher at the King’s India Institute, King’s College London.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.