Wheat vs. Jowar: Can India’s MSP Strategy Avert a Groundwater Crisis -1?

A farmer in Bhopal district, Madhya Pradesh, showcasing her thriving wheat fields. Credit: Madiha Khanam

Despite 2023 being declared as the 'Year of Millets' in India, celebrating the nutritional and environmental benefits of these ancient grains, the truth is, India is still hooked on to growing wheat. A six-month investigation by contributors to Newsclick shows how wheat, fuelled by decades of State-backed incentives, dominates farmlands across India, while millets like jowar remain sidelined despite their low water requirements and outsized nutritional benefits. Farmers continue to prefer water-intensive wheat cultivation, driven by entrenched market systems, better profitability and government support mechanisms heavily skewed in their favour. Many Indians once ate a millet-based diet. Over time, it faded from farms and plates. As water scarcity looms, one question persists: Can India turn back time and shift from water-intensive wheat back to millets like jowar to ensure future food security?

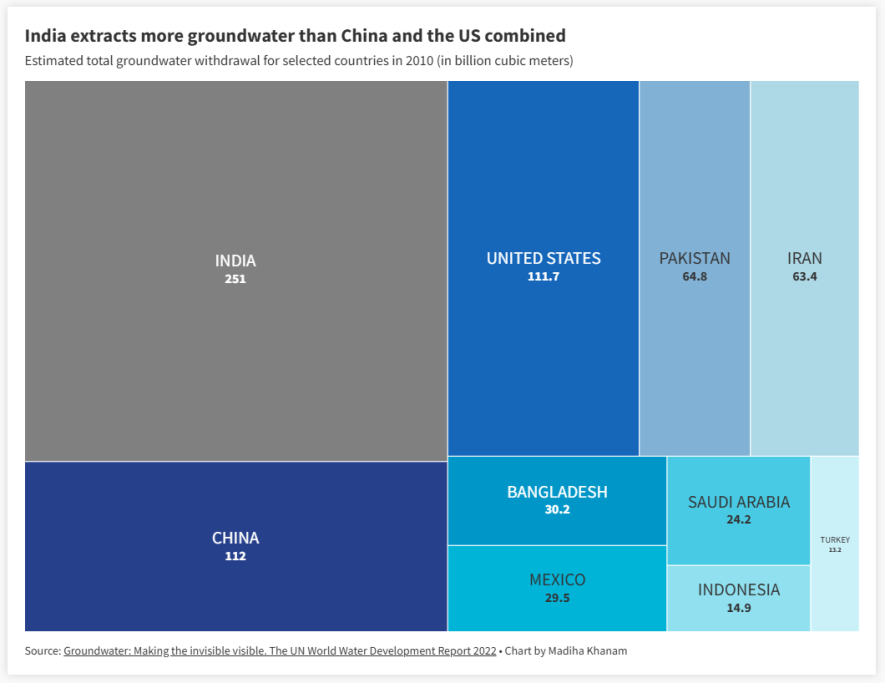

Conversations with experts and farmers expose the entrenched challenges, from economic disincentives to the lack of systemic support, leaving India’s sustainability goals in agriculture at a crossroads and calling into question the government’s true commitment to more sustainable farming practices. According to the United Nations World Water Development Report 2022, India extracts more groundwater than China and the US combined, making it the world's largest user, with over extraction worsening its water crisis amid global shortages. It means time is running out for India to chart a course toward a sustainable future for agriculture.

Rise of Industrial Wheat at Cost of Artisanal Jowar

India’s farms have shifted heavily toward wheat, fuelled by government support and market demand. But this change has come at the cost of traditional grains like jowar, which are more resilient to drought and require far less water.

Our exploration of the economics of wheat and millets reveals how government incentives, changing consumer preferences, and market forces have fuelled wheat’s dominance while sidelining jowar. This shift has deepened India’s water crisis and made food systems more vulnerable to climate shocks, affecting long-term food security.

Intensive Farming Practices Push Wheat up, Millet out

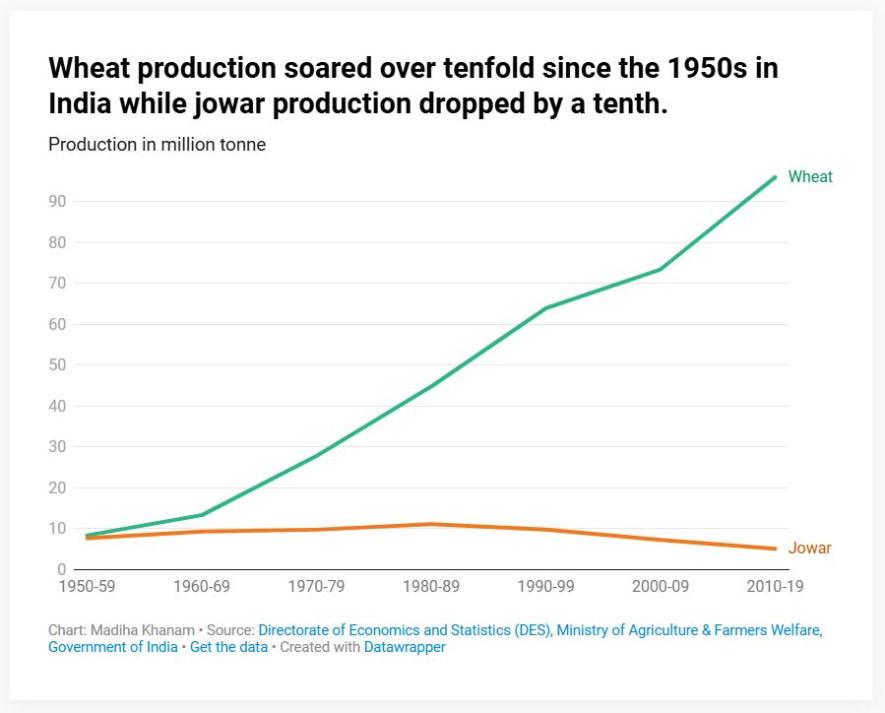

Over the decades, farms growing wheat expanded significantly since the 1950s, with land area for wheat tripling and production soaring more than tenfold. This boom was largely driven by the Green Revolution in the 1970s, which introduced high-yielding wheat varieties supported by irrigation and subsidies. In contrast, jowar cultivation faced a steady decline, with the area shrinking to less than a third and production dropping by a tenth, a trend that began after the 1980s.

While jowar—once a staple—has faded into the background, it struggles to find a place in the mainstream food system. The Green Revolution was a turning point for Indian agriculture, prioritising crops like wheat and rice to combat food scarcity. It brought about technological advancements, including hybrid seeds, chemical fertilisers, and large-scale irrigation. While it ensured food security, it also established a system favouring water-intensive crops, sidelining resilient millets like jowar.

A farmer, Babu Lal recalls: “The main reason people in the village don’t grow jowar anymore is that you can only grow one crop if you decide to grow jowar.” Unlike wheat, which benefits from irrigation and can be followed by another crop in the same year, jowar relies on rain and takes up the entire season. He adds, ‘Isme ghaate ka sauda hai,’ meaning it is a business loss.

“The whole village used to grow jowar earlier because we had very limited irrigation resources, especially around 1984 and before. Back in 1984, farmers were treated with much less respect, almost like beggars, when they used to grow jowar. They used to face such high electricity bills that they would fall into huge debt,” he added.

A farmer in Bhopal district, Madhya Pradesh, showcasing her thriving wheat fields. Credit: Madiha Khanam

Madhya Pradesh has seen wheat production more than double in the past decade. In contrast, Gujarat, Haryana, and Madhya Pradesh have reduced jowar production to about half during the same period. Dhar district in Madhya Pradesh is the leading wheat producer while Solapur district in Maharashtra grows most of the jowar in the country.

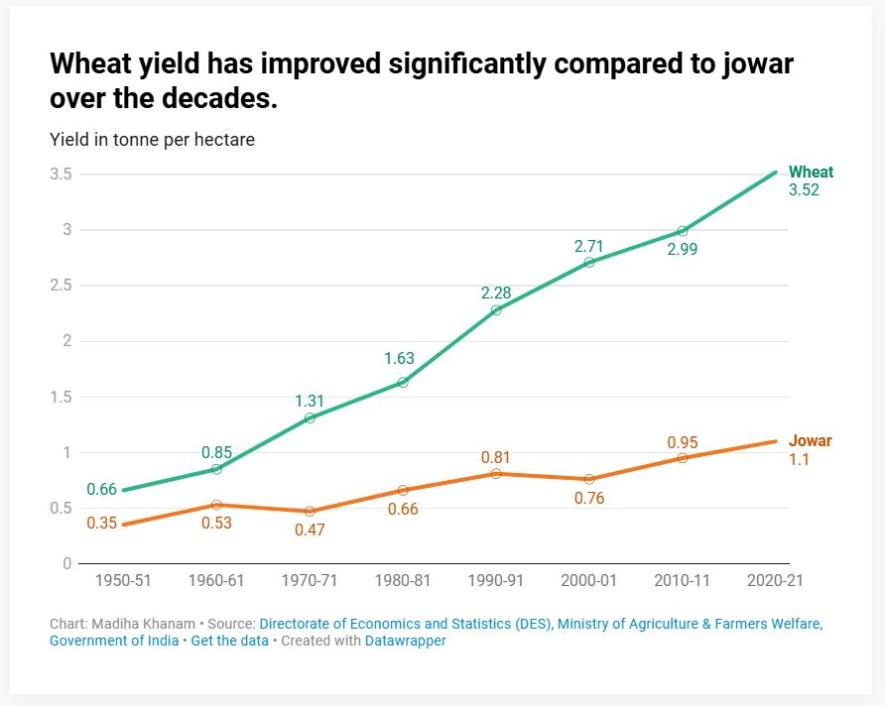

The yield of wheat has improved significantly in recent years, with Madhya Pradesh leading the way, showing more than one-third increase. Andhra Pradesh has the highest yield for jowar in the country, though it still falls short compared to wheat yield in Madhya Pradesh. This means that farmers will get triple the wheat out of every hectare than they would if they grew jowar.

Wheat is Tougher Than Millet Though Latter at Scale is Hardier

Purohit explains why wheat remains a top choice for Indian farmers. “Its resilience allows it to endure extreme weather with minimal losses, requiring less labour than other crops. Even with a 10-20% yield drop due to climate change, it stays reliable. Storms or heavy rain may bend plants or shed some grains, but the crop survives. As long as water is available, farmers will stick to wheat—unless an alternative crop (jowar or any other millet) proves just as hardy.”

Wheat has a long shelf life and is used in many industries and in products like bread, roti, maida, and bakery items. On the other hand, millets, like jowar and bajra, have a short shelf life. Farmers cannot store them for long, or they will spoil. While jowar and bajra can be used as raw materials to make different kinds of products, there’s limited demand.

Madan Lal, a 40-year-old farmer who owns 15 acres of farmlands in Bhopal district, Madhya Pradesh, talked about the agronomic barriers related to jowar cultivation. He explains, “If we look at the yield, the jowar plant can grow up to 10 feet tall, but the size of the fruit remains fixed. You get about 500 seeds in return for sowing just 1 seed of jowar. In comparison, for wheat, you get 20 to 40 seeds for every seed you sow. The key difference is that wheat seeds can be sown very close to each other, whereas jowar requires a minimum distance of 1 to 1.5 feet (an arm's length) between each seed for it to grow properly.” This means jowar must be sown with wider spacing between plants, limiting the number of seeds and reducing overall yield.

Bhram Singh,38, who owns four acres of farmland in Rasooliya Pathar, Bhopal district, Madhya Pradesh, grows wheat and soybean. He shares his concerns related to jowar cultivation. “The main issue is if we grow jowar, we can only grow one crop. If we plant it in the rainy season (June), the flowers start appearing around November. By the time the jowar is harvested, it will be too late to sow wheat. The soil becomes extremely dry (‘kaldi’) because jowar extracts all the moisture from it, making it undesirable for any other crop. You would have to wait for the next rainy season before the soil can regain its moisture. But if we grow wheat, the soil retains enough moisture, so we can grow soybean next.”

Farmers share their perspectives on wheat and jowar cultivation at a tea stall in Bhopal district. Credit: Author

Rishiraj Purohit, Programme Manager (Sustainable Agriculture) at Samarthan NGO, Bhopal, explains that the challenge of soil dryness after jowar cultivation can be addressed through better soil management and crop planning. He emphasises that the government needs to invest in the initial transition phase, support research for improved jowar and millet varieties, and strengthen extension services to guide farmers on sustainable farming practices.

Purohit, who has worked extensively on the promotion of millets in Madhya Pradesh explains that a major hurdle in expanding jowar cultivation is that the fruit of jowar is exposed, making it highly susceptible to bird attacks. If an entire village cultivates jowar, the birds' numbers get spread out across the fields, reducing the impact of the attacks. But if only one farmer decides to grow jowar or bajra, they’ll face severe bird damage, and the production will likely be lost.

Weak Markets Make Millets Less Profitable

The economics of jowar production is also a concern. If the yield of jowar is only 8-12 quintals per acre, the cost-benefit ratio for jowar does not look very impressive when compared to wheat. Jowar’s value addition in the market is very low. It has fewer processed and high-value products in the market, reducing its profitability compared to wheat. “You’ll find jowar priced quite high in the market, but if you buy directly from a farmer, it’s much cheaper. For instance, jowar flour costs around Rs. 100 per kg in the market, but when bought from a farmer, it’s available for Rs. 20-25 per kg,” says Purohit.

People in India only eat about a tenth of the millet they did 50 years ago. The per capita consumption of millets in India has dropped to just 30.94 kg/annum in 1960 to just 3.87 kg/annum in 2022. Most people do not eat millet as an unprocessed stable food anymore. More than half of the millet consumed in urban India comes from processed or value-added products, with online retailers and e-commerce platforms being the main distribution channels. These products include millet-based flour, breakfast cereals, energy bars, snacks, pasta, cookies, and ready-to-cook mixes. Currently, jowar is mainly consumed by the elite class, who are more health-conscious and have access to media coverage touting its health benefits.

To be continued.

(Part 2 of this series will examine the ecological consequences of the shift from jowar to wheat).

Note on Methodology

This story combines data analysis with fieldwork and expert interviews to explore the sustainability of cultivating wheat and jowar, particularly in the context of water usage and government support mechanisms. The analysis drew from several key datasets, including reports on the national area, production, and yield of wheat and jowar sourced from Agriculture Statistics at a Glance (2013–2022). District-level data on the major contributing regions for both crops were obtained from the Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, spanning the period from 2013 to 2023. Water footprint statistics were derived from Mekonnen and Hoekstra’s study, The Green, Blue, and Grey Water Footprint of Crops and Derived Crop Products (Value of Water Research Report Series No. 47), which included state-level data for India. Groundwater availability and utilization data covering the same period were acquired from the Central Groundwater Board, Ministry of Water Resources. Additional information on irrigation, procurement, and Minimum Support Prices (MSP) was sourced from government reports, including those published by the Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Food Corporation of India, and parliamentary records.

The analysis, conducted using spreadsheet tools, examined trends in production, irrigation, and procurement, correlating water footprint data with crop yields to assess sustainability. Ground-level perspectives were incorporated through interviews with farmers in Rasooliya Pathar and Ratanpur, Bhopal district, Madhya Pradesh, shedding light on the challenges of cultivating wheat and jowar.

Expert insights from figures such as Prof. Himanshu (Jawaharlal Nehru University), Kiran Kumar Vissa (Alliance for Sustainable & Holistic Agriculture - ASHA), and Dr. Siraj Hussain (former Union Agriculture Secretary) provided context on the MSP framework and agricultural economics. Discussions with Rishiraj Purohit (Samarthan NGO) added depth to the analysis of millet production and challenges associated with millets in India.

Madiha Khanam is an architect, urbanist, and researcher. Her work focuses on cities, urban regeneration, geoinformatics, agriculture, water, and environment.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Environmental Data Journalism Academy- a program me of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and Thibi.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.