Water Security, Cost of Wheat to Jowar Shift -2

A small-scale farmer using drip irrigation in the early stages of wheat cultivation to cope with water shortages. Credit: Madiha Khanam

Wheat thrives on assured irrigation, but its water-intensive nature is pushing India’s groundwater reserves to the brink. As water scarcity deepens, the cost of favouring wheat over millets may soon become too high to sustain.

Part 1 of this six-month investigation into the long-term impact of a shift from jowar to wheat explores how wheat’s dominance over millet makes economic sense.

In Part 2 we look at the environmental perils of wheat cultivation and how it might reverse the fortunes of wheat and millet, if water lasts long enough…

Wheat is Sucking Dry India’s Groundwater

In 2019, India withdrew more freshwater than any other country in the world. At almost 650 billion cubic metres, the withdrawals were equal to emptying 260 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.

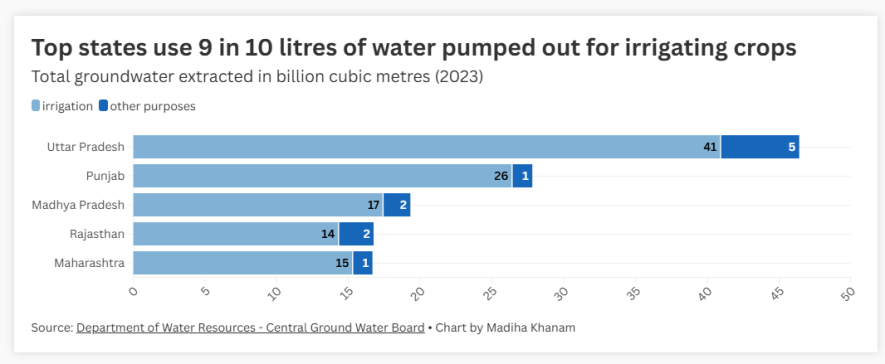

Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan are the top groundwater extracting states. Nine out of 10 litres of water pumped out is used for irrigating crops in the top groundwater extracting states. Growing wheat has significantly intensified water use in three out of the five states that consume the most water: Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan.

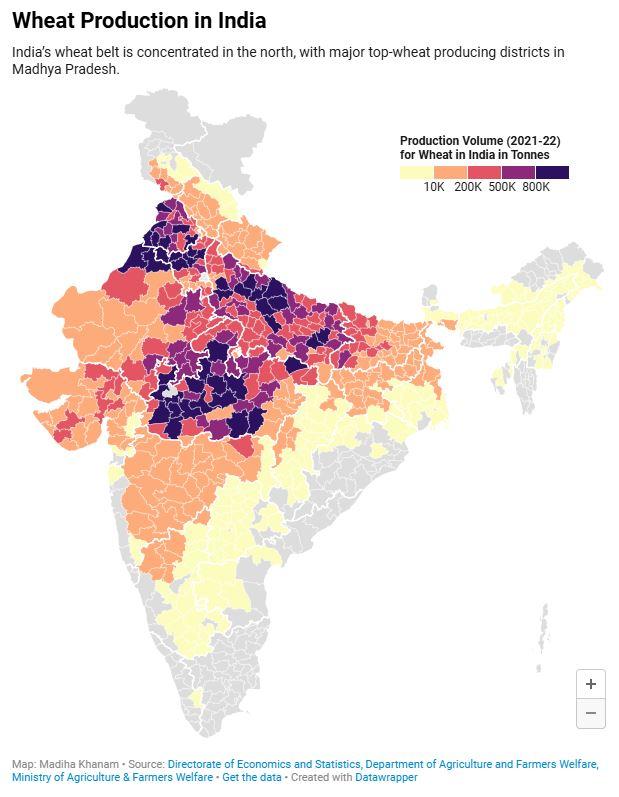

Wheat has spread across India just as its groundwater supply has shrunk to one of the worst in the world. Since the 1950s, farmers have increased irrigation for wheat, expanding coverage from about one-third of the land to nearly all of it by 2020.

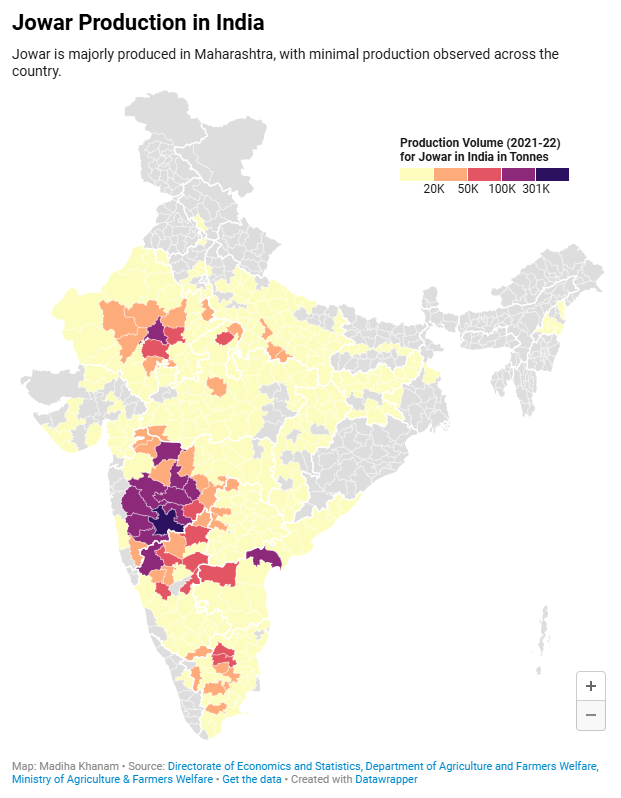

In contrast, farmers growing jowar have seen only a slight rise, growing from one-30th to one-10th, which is covering just a small fraction of the total land under jowar. At an all-India level, wheat has experienced a rise in irrigation eight times greater than that of jowar. The reality is India only has enough water to sustain long- term jowar cultivation, not wheat.

Wheat cultivation requires extensive irrigation, often relying on groundwater, which is already being overexploited in many regions. As the area under irrigation expands, the demand for water increases, leading to a significant depletion of groundwater levels. This creates a vicious cycle: where, over time, water runs out to quench the thirst of wheat, so farmers drill deeper to find more water. Eventually, resources become compromised, making it difficult for farmers to continue relying on water-guzzling crops like wheat.

When asked about water scarcity caused by wheat cultivation, Rishiraj Purohit, Programme Manager (Sustainable Agriculture) at Samarthan NGO, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, explains how the shift from jowar to water-intensive wheat has strained groundwater resources. When tube wells were first introduced in Madhya Pradesh, they tapped into the basalt layer beneath the surface. However, with farmers continuously cultivating wheat year after year, water levels in the region have significantly depleted.

A small-scale farmer using drip irrigation in the early stages of wheat cultivation to cope with water shortages. Credit: Madiha Khanam

The Malwa plateau, which had water reserves accumulated over a thousand years, is now being accessed through tube wells reaching depths of 400-500 feet, compared with the earlier 100-200 feet. As a result, many tube wells are drying up. Farmers sow wheat in October-November, but by December-January, groundwater resources begin to dwindle. To cope, new tube wells are frequently installed. But eventually, drilling deeper will not work, either.

This challenge affects farmers who rely on wheat cultivation and have limited water resources. They often struggle to access adequate groundwater for irrigation until March-April—a problem that didn’t exist earlier.

Continuous wheat cultivation, without allowing sufficient time for water to recharge deep into the soil, exacerbates this issue.

Jowar is a Water-Saving Crop

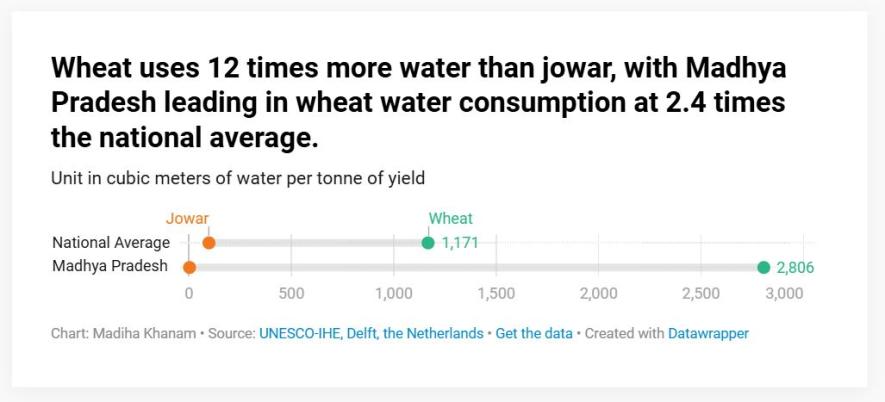

Jowar is indisputably a more water efficient choice for states in India concerned about their groundwater use, yet it is disappearing from the fields of Madhya Pradesh. Wheat in India uses 12 times more water than jowar. Madhya Pradesh pumps out the most water for growing wheat in the country, about 2.4 times the national average. Wheat requires 1171 metric cube per tonne of water while jowar requires only 98 metric cube per tonne.

Over the past decade, farmers in Madhya Pradesh have increased the area irrigated for wheat by about two-thirds, while jowar farmers in Maharashtra and Karnataka have seen their irrigated area shrink by nearly one-third. In 2021-2022, Madhya Pradesh has the largest irrigated area for wheat in the country, with more than half of its irrigated land dedicated to wheat cultivation. Despite having the highest share for jowar, Karnataka has just one-hundredth area allocated to jowar cultivation.

A tube well supplying irrigation to a wheat field in a village in Bhopal district, Madhya Pradesh, highlighting farmers' reliance on groundwater for cultivation. Source: Author

Depleting Groundwater to Irrigate Wheat, a National Problem

Farmers across the country are making the decision to run the risk of running out of water to keep up intensive wheat cultivation.

At the national level, Punjab extracts the most water among the top wheat-producing states, exceeding the limit by over 1.7 times. Meanwhile, Rajasthan leads in groundwater extraction among the top jowar-producing states, drawing nearly 1.5 times the limit.

The area under wheat has grown steadily by more than one-tenth in the past 10 years, while the area under jowar has nearly halved. Wheat in India is mainly produced in the northern belt. More than three-quarters of India’s wheat is grown in five states: Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Haryana.

Over four-fifths of India's jowar is grown in just three states: Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Rajasthan. In the past decade, wheat production in India increased by a quarter, while jowar production fell by more than a third.

In 2023, three out of the top five wheat-growing states are over-exploiting groundwater for irrigation, while only one of the top five jowar-growing states is extracting groundwater beyond its limit.

According to a Madhya Pradesh farmer, wheat requires four rounds of irrigation. Though water is generally available in November and December, shortages emerge in January and February, forcing farmers to rely on deeper tube wells. Many wells have already dried up, leading farmers to dig new ones, though with no guarantee of finding water. This cycle of depletion and uncertainty underscores the harsh reality farmers face today.

Often, farmers grow wheat without fully accounting for the ecosystem's limitations. When water resources fail to support wheat cultivation, they are forced to consider alternatives like jowar, even if they are reluctant to switch. As irrigation challenges worsen, farmers will inevitably need to rethink their crop choices. The pressing question remains: what will they grow when water is no longer sufficient for wheat?

To be continued.

(Part 3 of this series will look at the government’s role in promoting unsustainable levels of wheat production and what policies would be required to shift to more sustainable agricultural practices.)

Madiha Khanam is an architect, urbanist, and researcher. Her work focuses on cities, urban regeneration, geoinformatics, agriculture, water, and environment.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Environmental Data Journalism Academy- a program me of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and Thibi.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.