Upside-Down Midas

(This article was written before Habib Tanvir passed away)

Born in the 1920s, they are the first generation of independent India’s great theatre directors: Habib Tanvir (b. 1923), B.V. Karanth (b. 1928), Utpal Dutt (b. 1929), Ibrahim Alkazi (b. 1923), Satyadev Dubey (b. 1936). Their contrasting careers make a fascinating study.

Alkazi, patrician, disciplinarian, master of the monumental. He began his theatre work in Bombay with Dubey, went to England to get trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, eventually became Director of the National School of Drama, where he imparted to students what he had learnt at RADA. He quit the NSD in the early 1980s, and apart from a brief return in the late 1980s, he has stayed away from theatre ever since. Karanth, peripatetic minstrel, visionary, musical genius. He began with the Gubbi Veeranna theatre company, trained in Hindustani music in Benaras under Pt. Omkarnath Thakur, joined the NSD as a student in 1962, eventually succeeded Alkazi as its Director, and went on to become the first director of two repertories: the Bharat Bhavan Rangmandal in Bhopal, and the Rangayana in Mysore. He dabbled in cinema as well, directing some Kannada films, and giving music for many others. Utpal Dutt, feisty Marxist, acid-tongued, master of heroic melodrama. Beginning with English theatre and Shakespeare in Calcutta, he flirted all too briefly with the Indian People’s Theatre Association, formed the People’s Little Theatre, acted in Jatra, and acted in cinema—in Bengali films by Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen, but also in trashier Hindi films, through which he subsidized his theatre work. Satyadev Dubey, rebel, teacher, master of speech. Originally from Madhya Pradesh, he is a naturalized Maharashtrian, has directed dozens of plays, mostly in Bombay, but also many for the NSD, he has mentored playwrights and introduced generations of actors, including some very famous ones, to the difficult pleasures of the spoken word. Unique among the five, he has not headed a theatre institution, nor has he run a theatre company for any substantial length of time. He, too, has dabbled extensively in cinema, especially as script and dialogue writer to his friend Govind Nihalani.

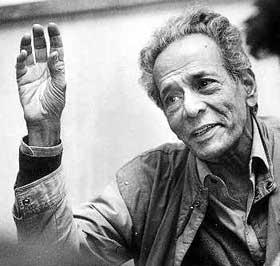

And then there is Habib Tanvir. Like Alkazi, he went to RADA, but unlike him, shed his learning like a snake’s skin. Like Karanth, he experimented extensively with Indian theatrical forms, especially the Nacha of Chhattisgarh, but unlike him, he always stayed close to the modern European theatre as well. Like Utpal Dutt, he is an actor-director-playwright-manager, but unlike him, did not subsidize his theatre work by earnings from cinema. Like Dubey, he too is from central India, but unlike him, he sought his theatrical identity in the region.

And unlike the other four, Habib Tanvir’s identity is inextricably tied up with that of his theatre company, the Naya Theatre. Many of its best-known members are dead, but till recently, the Habib circus was quite a sight.

There was his wife Moneeka, who, planted in a chair, made sure the costumes were ironed, the props in place, the toilets clean, the actors fed. Her knees ached, but she had perfected the art of dozing while sitting. There is Nageen, their daughter, deceptively fragile looking, with a clear, resonant singing voice that never slips a note. Then there are the actors: Bhulwaram, now dead, who joined Habib Tanvir in 1958, an year before Naya Theatre itself was formed, with majestic white hair like a halo around his dark, gentle face—probably Chhattisgarh’s last great singer; Govindram, now retired, an actor of immense skill, dignity, and simplicity; Devilal Nag, composer of countless songs; the gentlemanly Udayram, actor and organizer; Ramcharan, past 80 and retired, the funniest stage actor I have ever seen; Ramchandar, younger and handsome in a rugged sort of way, educated and, along with Dhannu, the organizational backbone of Naya Theatre; Chaitram, Bhulwa’s son, mulish and impulsive in equal measure, the exterior only partly concealing a baby’s heart; Agesh, Devilal’s daughter, still learning the actor’s craft; Shankar, clarinet player, whose ex-wife, an ex-Naya Theatre actress, is married with child to another ex-Naya Theatre actor; Amardas the tabla player, who occupies his mouth with tobacco rather than talk; finally, Shyama, who has spent many years playing those unheralded bit parts without which the play would be incomplete. Shivdayal, one of the original 1958 group, who spent years in jail on a false criminal charge, died in August 2003. Brijlal, another of the senior actors, died a little earlier. Some of Naya Theatre’s finest performers died even earlier: Madanlal, Thakurram and Laluram, the great Nacha performers; Fidabai, an actress of incomparable power, grace, and subtlety; Malabai, a singer with an astonishing range.

And there is, of course, the Pied Piper himself. His father was a Pathan from Peshawar, and Habib Tanvir retains the arrogance and quiet determination of those sturdy tribesmen. Urbane and sophisticated, pipe in hand, he is a man of sartorial panache, charming and wickedly funny, delighted with the ordinariness of the world. Sage-like and forever immersed in work, he sizes up people instantly. Grand patriarch, benevolent dictator, he can surprise you with a completely open and accommodating mind. With his own writing, he can be brutal, deleting fabulous passages because, in performance, they hinder the flow. To actors of intelligence, he can give unlimited space—well, almost. For the rest, he is a tyrant. As someone once said of Marx, freedom of man does not include for him the freedom to be stupid.

This circus has been on the road since 1959, and nearly fifty years later, after some have died, some retired, and some gone away, finally looks like it is going to wind up sooner than later.

The Early Years

Christened Habib Ahmed Khan by his hafiz father, the young Habib, a budding poet, took the takhalluz ‘Tanvir’. The takhalluz stuck, and he too has composed poetry through his life. (This is, of course, apart from the hundreds of songs he has written for his plays.) He matriculated from Raipur in 1942, graduated from Morris College, Nagpur, in 1945, and went to Bombay to pursue an acting career in cinema. It was an exciting time to be in Bombay. The film industry was expanding, new talent was emerging, and he soon had a circle of friends among film personalities, writers, actors and poets. The War was winding down, the Quit India movement had already poured volatile youth on the streets, and he recalls the heady days of the RIN Mutiny. The Indian People’s Theatre Association was formed in Bombay in 1942, and he soon found himself a part of it, drawn to the personality of Balraj Sahni. He did a variety of things to support himself, including working for the radio, but this was the time when he made, partly consciously, partly fortuitously, the decision to devote his energies not to cinema, nor to poetry, but to the theatre.

Habib Tanvir shifted to Delhi in 1954, and worked for Qudsia Zaidi’s Hindustani Theatre. He also worked in children’s theatre, and some of his playscripts from that time are still delightful. He met the young actress/director Monika Misra here, and although they did not take to each other initially, in time they were married. His first significant play, Agra Bazaar, dates from this time. It is a celebration of the life and work of the plebian poet Nazir Akbarabadi, an older contemporary of Ghalib’s. Hardly any biographical information is available about Nazir, so Habib Tanvir was forced to do a play in which the protagonist never appeared. The play, as the title suggests, is set in the bazaar, the locale that has kept Nazir’s poetry alive. With virtually no plot, the play was a stylistic novelty in its time. Habib Tanvir drew into the play the residents of Okhla village in Delhi, in an experiment that was to be repeated on a more sustained basis with Chhasttisgarhi rural actors some years later.

Qudsia Zaidi died prematurely, and Habib Tanvir set off to train at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA), London. He was already in his early thirties then, not a novice learning the rudiments of his trade, but an experienced craftsman of some standing. At RADA he learned many things, including British discipline, the principles of blocking and some tricks of a director’s craft, but mostly he learned what he did not want to do. It seemed to him that Western theatre, particularly English theatre, was too rigid to allow the free movement that Indian theatre demanded. Western theatre, following Aristotle, demanded the unities of time, space and action, while Indian theatre, both the ancient Sanskrit and the rural, broke these unities constantly, admitting only one unity, that of rasa. For example, ‘In act II of Mrichchhkatika, the Samvahak is being pursued by a couple of fellow gamblers. It is a street scene. He first enters a temple and then Vasantasena’s house in the course of the chase. In both instances the scene is enacted—replete with dialogue and visuals—simultaneously inside as well as out in the street. Some translators have divided this act into Part I Scene i, Scene ii, Scene iia, Scene iii, etc., refusing to face up to the fact that Sudraka, the playwright, had no use for such unity of space. Unity of time is likewise broken. . . . The judge orders an officer to go on horseback to the Pushpakarandak garden to see if a female dead body is lying there. In the very next line, the officer confirms the existence of the dead body in the garden. The point here is that the officer has not gone off the stage.’

He roamed around in Europe for a while after that, watching plays, learning gypsy songs, sometimes earning money for passage by singing at bars songs from his native Chhasttisgarh, and eventually arrived in Berlin, determined to meet Bertolt Brecht, whose Berliner Ensemble was giving practical shape to the master’s plays and dramatic theory. The year was 1956, and by the time he made his way to the Berliner Ensemble, he discovered that Brecht had died a couple of months earlier. But Brecht’s productions were alive, and Habib Tanvir got to see those. He also got to see the legendary actor Helene Weigel, whom Brecht had married, and was struck by the simplicity of her expression. Indeed, simplicity and directness were the hallmarks of Berliner Ensemble productions under Brecht, and Habib Tanvir must have been reminded of Sanskrit drama, with its ‘absolute simplicity of technique and presentation’. Simplicity, he felt, was ‘intrinsic to Sanskrit drama’: ‘it had to be so in order that its complicated plot is put across in a comprehensible manner’.

By the time he got back to India, he was determined to unlearn much of what he had learnt at RADA. It wasn’t easy.

The Prism of Chhasttisgarh

The majority of serious theatre-goers today started watching theatre in the 1970s and later; at any rate, the number of those who remember plays from the 1960s and earlier is dwindling. I myself started doing, and watching, theatre seriously enough only in the mid-1980s. We encountered Habib Tanvir fully-formed. Gaon ka Naam Sasural, Mor Naam Damaad, his first significant Chhasttisgarhi production, was done in 1972. Charandas Chor was created during 1973–74, and won the Edinburgh Fringe First Prize some years later, catapulting its creator and his band of rural actors to stardom. It even did a run on the London stage, playing to packed audiences. Mitti ki Gaadi, his Chhattisgarhi adaptation of Sudrak’s Sanskrit classic, was done in 1977; Bahadur Kalarin, an oral rural Oedipal tale, followed soon after. Shajapur ki Shantibai (Brecht’s Good Person of Schetzuan), with the incomparable Fidabai in the lead, was done in 1978, Lala Shohratrai (Molière’s Bourgeois Gentleman) in 1981. In other words, by about the mid-1970s, Habib Tanvir had already evolved his distinctive idiom of modern theatre, and subsequent years have basically seen him elaborating this idiom, refining it, polishing it, rather than evolving a new form. Those of us who have come to watch and love his theatre after this time tend to take this idiom, his style, for granted. It can therefore be quite easily forgotten that it took him fourteen long years, from 1958 to 1972, to come to it.

On Habib Tanvir’s theatre, it is quite common to hear two views. One sees a development of the IPTA legacy in him, the other sees him as a practitioner of ‘folk’ theatre. Both are incorrect. IPTA sought to build an all-India network of revolutionary cultural groups in close association with the Communist movement. Habib Tanvir, after his early years with IPTA, has never again done that kind of work. Certainly in his theatre practice there isn’t even a whiff of IPTA: while IPTA used ‘folk’ forms essentially as carriers of revolutionary ideology to ‘the masses’, Habib Tanvir has fashioned a popular modern theatre, borrowing elements from rural dramatic traditions, that has been more often than not been utopic rather than revolutionary.

Habib Tanvir got his first set of six rural actors in 1958. He did several plays between then and 1972, but most were, to a greater or lesser extent, failures. These failures led him to wonder: the rural actors, in their own setting, when they do Nacha, are fabulous. What makes them stilted and trite when they act in his plays? He identified two main faults: ‘mother tongue and freedom of movement’. ‘[I realized], after many years, that I was trying to apply my English training on the village actors—move diagonally, stand, speak, take this position, take that position. I had to unlearn it all. I saw that they couldn’t even tell right from left on the stage and had no line sense. And I’d go on shouting: Don’t you know the difference between the hand you eat with and the one you wash with? . . . I realized that those who were for years responding to an audience like this [without bothering about whether the audience was on one side, or three, or four, or whether some of them were sitting on the stage] could never try to unlearn all this and rigidly follow the rules of movement and that was one reason why Thakur Ram, a great actor [one of the 1958 six] wasn’t able to be natural. Another reason was the matrubhasha—he wasn’t speaking in his mother tongue, so it jarred on my ears, because he was speaking bad Hindi and not Chhasttisgarhi, in which he was fluent, which was so sweet. This realization took me years—naïve of me, but still it took me years. Once I realized it I used Chhasttisgarhi and I improvised, allowed them the freedom and then came pouncing down upon them to crystallize the movement—there you stay. And they began to learn. That quite simply was the method I learnt.’

That was the method all right, but it was to be used to channelize the rural actor’s energy to tell modern stories. His dramaturgy and stagecraft is also modern. His Kamdev ka Apna, Basant Ritu ka Sapna (Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream) is played on a bare stage, the only element of set being a hand-held, beautifully embroidered half-curtain which sometimes reveals, sometimes hides, and sometimes becomes a backdrop to, the action. With its simplicity, its directness and minimalism, Habib Tanvir’s theatre would have been considered avant-garde had it not been so popular, and so funny. If you talk to his actors, they all, without exception, make the distinction between Nacha, where they originally trained, and ‘theatre’, that is, Habib Tanvir’s theatre. His is a theatre of modern sensibilities, of modern concerns. Besides his own plays, look at the range of dramatists he has tackled. The ancient Sanskrit writers Sudrak, Bhasa, Visakhadatta and Bhavabhuti; European classics by Shakespeare, Molière and Goldoni; modern masters Brecht, Garcia Lorca, Gogol and Gorky, and even Wilde; and Indian writers Rabindranath Tagore, Sisir Das, Asghar Wajahat, Shankar Shesh, Safdar Hashmi and Rahul Varma. He has adapted stories by Premchand, Stefan Zweig and Vijaydan Detha for the stage, besides adapting oral tales from Chhasttisgarh. The stories he tells are the stories of our times, told with the simplicity and directness and energy of the rural performing traditions.

Habib Tanvir, then, is a citizen of the world, borrowing, reading, soaking up influences indiscriminately, but he has become, through a long, hard, creative struggle, a resident of Chhasttisgarh. Chhasttisgarh is the prism that refracts his creative expression. He is writing his autobiography, Ek Matmaili Chadariya—a life woven with multiple threads, a life the dusty colour of earth. He is a Midas turned upside-down: whatever he touches loses its sheen, it becomes rough and turns to Chhasttisgarhi. As Brecht once put it: ‘True art becomes poor with the masses and grows rich with the masses.’

Celebration of the Plebian

This is the man the Hindu Right has hounded since the early 1990s. To argue, as the Hindu Right does, that Habib Tanvir is anti-Hindu and, by extension, anti-Indian, is of course a reflection not on the man and his work, but of the depraved, pea-sized worldview of his attackers. To spit at the moon is to spit on your own face.

Yet Habib Tanvir is no revolutionary. Indeed, he, along with a large number of intellectuals and artists close to the CPI, flirted for a while with the Congress (I) in the 1970s. He campaigned for the party in the 1971 elections with a play called Indira Loksabha. In what some saw as a return of the favour, he was nominated to the Rajya Sabha, and, to the dismay of those to the left of the CPI, he did not resign his seat when the Emergency was declared in 1975. It is only later, in the 1980s, that he became, in private conversations at least, more critical of the Congress (I). He directed a play for Jana Natya Manch in 1988, and was in the forefront of the protests that followed Safdar Hashmi’s murder at the hands of Congress goons in 1989. Over the years, he and the left have both moved closer to each other, and in the context of the attacks on him by the Sangh Parivar over the last decade and his refusal to bow to their dictates, he has become something of a hero for left cultural activists.

The politics of his plays are somewhat hard to categorize. If there is one theme that runs consistently through all his creative output, from Agra Bazaar and even earlier to the present, it is the celebration of the plebian. The culture, beliefs, practices, rituals of the Chhattisgarhi peasants and tribals, their humour, their songs and their stories, all this is what has given his theatre its incredible vitality. His characters do not lack religiosity, but have a down to earth commonsensical relationship with god. Charandas prostates himself in front of god in all sincerity before purloining the idol. A peasant or a tribal can turn a rock, a tree, an animal, anything, into god. Habib Tanvir is fascinated by this openness and eclecticism. He opposes Hindutva because, among other things, it seeks to destroy this freedom and regiment the belief structures and practices of peasants and tribals.

Habib Tanvir has been the enemy of parochialism, of bigotry, of fundamentalism, and of the kind of development that crushes the poor. If Jamadarin/Ponga Pandit critiques, in the lively, robust manner that he has perfected, the caste system, superstition and priestcraft, the other play that he has been extensively attacks Muslim fundamentalism: Asghar Wajahat’s Jis Lahore Nai Dekhya Voh Janmya hi Nai, the story of a Hindu woman left behind in Lahore after Partition. His latest production, Raj Rakt, based on Tagore’s Visarjan, is also a critique of superstition. An earlier play, Moteram ka Satyagraha, based on a Premchand story and written in collaboration with Safdar Hashmi, is a humorous look at what happens when religion starts meddling with politics. In the aftermath of the demolition of the Babri Masjid in December 1992, he produced for a Delhi group Sisir Kumar Das’s Baagh, an allegory on the communal tiger on the prowl. In 1999, he wrote and directed for Jana Natya Manch Ek Aurat Hypatia Bhi Thee, on the 4th century A.D. woman mathematician from Alexandria, lynched on the streets by Christian bigots. Sadak, a short play, is a comic critique of ‘development’ that ravages villagers, tribals, their land and their culture. Hirma ki Amar Kahani is a more profound look at what development has meant for tribals. An early short children’s play, Gadhe, is a rip-roaring take-off on the education system that produces asses. His latest production, Rahul Verma’s Zahareeli Hawa, is a fictional recreation of the Bhopal gas tragedy. Then there is Dekh Rahe Hain Nain, perhaps his most refined play philosophically, the story of a king’s futile quest for a calling that will harm no other being.

This, then, is Habib Tanvir, a man who represents two great traditions of Indian theatre—the tradition of the actor-director-playwright-manager, as well as the tradition of an active involvement, from the left, in larger social and political causes. The first tradition is now near-extinct, and Habib Tanvir is probably our last link to it. The second tradition, happily, survives, and some of the credit for this must go to Habib Tanvir himself, for showing us the way.

[Thanks to Moloyashree Hashmi, Javed Malick and Sameera Iyengar for nudging my excesses towards moderation and for pointing out lacunae, some of which, alas, persist.)

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.