Thirty-Six Years After Maliana Carnage, Victims Still Fighting for Justice

File Image

23 May 2023 is the 36th anniversary of the killing of 72 Muslims in Meerut’s Maliana village, allegedly by the notorious Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) of Uttar Pradesh.

After more than 800 “dates”, a shoddy trial and a weak chargesheet by the prosecution in the Meerut Sessions Court, on 31 March 2023, the additional district judge, Lakhvinder Singh Sood, set free all 40 people accused of the massacre on the grounds of inadequate evidence.

Three words can describe this recent judgment on the Maliana massacre of 23 May 1987, in which all 72 killed were Muslims—miscarriage of justice.

The Maliana case originally involved 93 accused. In the 36 years since the carnage, many accused died, while others “could not be traced”, leaving just 40 to face trial.

As atrocious as the verdict is, the entire case has been a travesty of justice right from the moment 36 years ago when the first information report (FIR) was filed.

1987 Meerut Riot

The Maliana massacre occurred against the backdrop of the riots in Meerut district, Uttar Pradesh, in May 1987. In what was supposedly a reaction to the opening of the disputed Babri masjid in 1986, on 17 May, Hindu and Muslim mobs clashed in Meerut City. Two days later, during a curfew in the city, the State government sent 11 Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) companies to help local police keep the peace.

However, according to the local media at the time and later, and investigations by national media and non-governmental organisations, the PAC started attacking Muslims across the district.

On 22 May, the PAC descended on the Hashimpura mohalla of Meerut and took away a large number of people in trucks while looting and burning houses and shops. While some taken away were sent to jails in Meerut and Fatehgarh, 45 Muslims were taken to the Upper Ganga Canal at Muradnagar in Ghaziabad and the Hindon River near the Uttar Pradesh-Delhi border, where they were shot and killed. Their bodies were thrown into the water. Meanwhile, 11 placed in the Meerut and Fatehgarh jails died in custody.

The PAC arrived in Maliana the next day. Eyewitnesses reported: “The PAC, led by senior officers including the commandant of the 44th battalion, RD Tripathi, entered Maliana about 2.30 pm on 23 May 1987 and killed more than 70 Muslims.”

Hundreds of locals accompanied the PAC contingent, who entered Maliana with guns and swords. All five entry and exit points of the locality were blocked before the 72 were killed. According to eyewitnesses, “Death was raining from all sides, and no one was spared, including children and women.”

Since the police itself carried out the carnage, no FIR was filed until Rajiv Gandhi, the then prime minister, visited Maliana with the then chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, Vir Bahadur Singh.

When Gandhi asked for investigations and reports, Yaqub Ali, a Maliana resident who had been severely injured in the attack, was compelled by the police to sign a document that he later learned was an FIR. This ‘FIR’ listed 93 people as accused in the massacre, all locals. No police personnel were named.

“I was one of those rounded up and mercilessly beaten when, without provocation, the PAC men began attacking houses while the mob indulged in looting and rioting,” Yaqub Ali said.

He added: “My ribs were broken, and I was in intense pain. I was made to sign the police complaint and didn’t even know what was written in it. It was much later that I learned that 93 Hindus had attacked us. The role of the PAC men has not even been mentioned.”

The names of the 93 accused were apparently lifted from the voter list of the area. While some named as accused had indeed participated in the massacre, many had not. When the police began to seek these 93 people to arrest them, it was learned that some had died long before 23 May 1987. Others died during the proceedings of the case, and still others went missing.

Alauddin Siddiqui, the lawyer representing the victims’ families, says, “[The verdict] is an abrupt decision at a time when proceedings were still on. Hearing on the 36 post-mortems had not taken place, and the accused had not been examined under Section 313 of the Criminal Code of Procedure [which deals with the power of the court to examine the accused to explain the evidence against him].”

Even the witnesses had not been carefully questioned. Fewer than ten eyewitnesses were examined in court, though there were 35 witnesses.

Additional district counsel Mohan said, “Several reasons were spelt out for the acquittal. First, the police had not conducted an identification parade of the accused. Secondly, the police had allegedly put 93 random names from the voter list, including those who had died years prior to the carnage. Then, no weapon was recovered from the site.”

A few days after the massacre, Vir Bahadur Singh declared ten people dead in Maliana. The next day, the district magistrate claimed 12 people had been killed, but in the first week of June 1987, after several bodies were found in a well, he accepted 15 people had been killed. Altogether, the State government accepted 56 deaths in Maliana and provided the victims’ families with compensation of Rs 20,000. Years later, a further Rs 20,000 was added to this meagre amount, bringing the total to Rs 40,000.

On 27 May 1987, Vir Bahadur Singh announced a judicial inquiry into the Maliana killings under the Commission of Inquiry Act of 1952. The inquiry was finally ordered on 27 August 1987 by Justice GL Srivastava, a retired judge of the Allahabad High Court. On 29 May 1987, the Uttar Pradesh government announced the suspension of PAC commandant Tripathi, who had ordered the firing in Maliana. Interestingly, allegations had also been made against Tripathi during the 1982 Meerut riots.

However, Tripathi was never suspended. Instead, he was awarded promotions until his retirement.

The continued presence of the PAC hindered the examination of witnesses from Maliana. Finally, in January 1988, the Srivastava Commission ordered the government to remove the PAC. Altogether, 84 public witnesses—70 Muslims and 14 Hindus—were examined by the commission, in addition to five witnesses from the administration. But the commission’s proceedings appeared to have been affected by apathy and indifference. It finally submitted its report on 31 July 1989, but it was never made public.

While the Srivastava Commission worked, the Uttar Pradesh government ordered an administrative inquiry into the riots in Meerut between 18 May and 23 1987. However, it excluded the events in Maliana and the custodial killings in the Meerut and Fatehgarh jails.

The panel, headed by Gian Prakash, the former Comptroller and Auditor General of India, consisted of Ghulam Ahmad, a retired Indian Administrative Service (IAS) official and former vice-chancellor of the Avadh University, and Ram Krishan of the IAS who was the secretary at the Public Works Department at the time.

The panel submitted its report within 30 days, as asked. On the grounds that the inquiry was administrative and ordered for its own purposes, the government did not place its report before the legislature or the public. However, the Kolkata-based daily, The Telegraph, published the full report in November 1987. It threw no light on the events of 23 May.

The run-up to the riots went like this: On 14 April 1987, communal violence broke out in Meerut, where the Nauchandi fair was in full swing. An allegedly drunken sub-inspector of police was said to have been struck by a firecracker while on duty. He opened fire, killing two Muslims.

The same day, Muslims had organised a religious sermon on the occasion of Shab-e-Barat, near the Hashimpura crossing, close to the venue of a mundan event at a Hindu family at Purwa Shaikhlal. Some Muslims objected to film songs being played on loudspeakers, which led to a quarrel.

The Hindu side is said to have fired first. The Muslims then allegedly torched some Hindu shops. Twelve people, both Hindus and Muslims, were reported killed. A curfew was imposed, and the situation was controlled, but the incident lit the fire that burnt Meerut for weeks.

On 17 May, there was rioting in Kainchiyan Mohalla. By 18 May, the violence had spread to Hapur Road, Pilokheri, and other areas. On 19 May, a curfew was imposed on the city, with 11 PAC companies brought in to help an estimated 60,000-strong local police.

From then on, the character of the “riots” changed—from clashes between Hindu and Muslim mobs to alleged killings of Muslims by the forces.

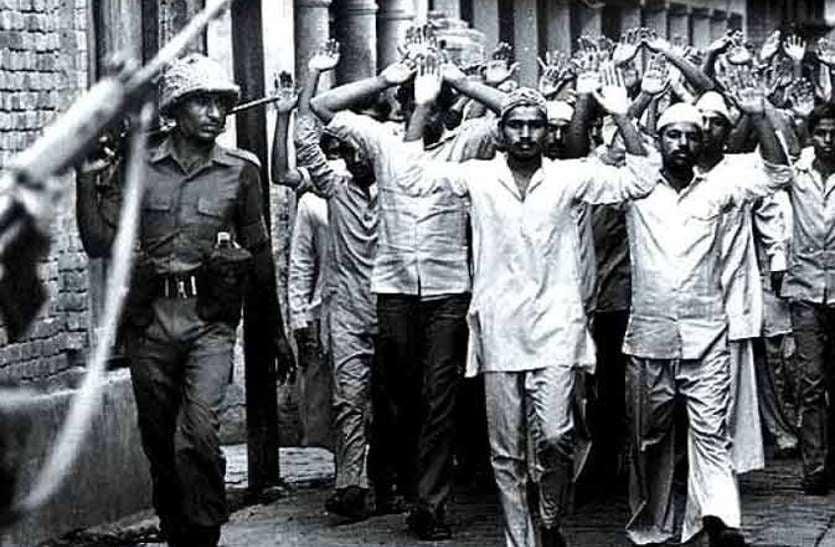

A day before the Maliana killings, the PAC and the army had surrounded Hashimpura on 22 May 1987. All residents were lined up on the main road, males aged above 50 or below 12 were segregated, and 46 among the rest were forced onto a truck.

They were driven to Muradnagar, and many were allegedly shot by the PAC. More than 20 bodies were found floating in the Ganga canal. The remaining captives were taken to the Hindon River near the Delhi border, where they were allegedly shot and dumped into the water. Altogether, 42 died.

A CBI inquiry ordered by Gandhi’s central government submitted a report that was never made officially public. A crime branch-CID (CB-CID) probe headed by then State police chief Jangi Singh, in its report, recommended prosecuting 37 PAC personnel and police officers. The State government sanctioned the prosecution of 19, of whom three died during the trial.

A chargesheet was filed in 1996, but none of the accused appeared before the Ghaziabad court until 2000, when 16 accused PAC men surrendered, got bail, and returned to resume service.

The Supreme Court transferred the case to Delhi in 2002 on a plea from the victims’ families, but hearings couldn’t begin till November 2004 because the Uttar Pradesh government had not appointed a public prosecutor for the case.

On 21 March 2015, the additional sessions judge held the evidence was insufficient and acquitted all the accused. Eventually, on 31 October 2018, Delhi High Court overturned the trial court order and convicted the 16 PAC personnel, sentencing them to life terms.

Jail killings

More than 2,500 people appear to have been arrested during the 1987 Meerut riots. Reports and records of 3 June 1987 suggest that five accused were killed in Meerut jail and seven in Fatehgarh jail. All of them were Muslims.

A magisterial inquiry into the Fatehgarh killings said that six inmates had died of injuries, some of them suffered in “scuffles that took place inside the jail”.

According to reports, several jail staff were suspended, and departmental proceedings were launched against the chief head warder, a deputy jailor, and the deputy prison superintendent.

Three murder cases relating to these six deaths were registered, but the FIRs contained no names despite certain officials being indicted by the inquiry. So, no prosecution was ever launched in these 34 years.

Independently, the state government ordered an administrative inquiry into the riots that occurred between 18 and 22 May but left out Maliana and the killings in Meerut and Fatehgarh jails.

PIL for justice

After 34 years passed without any movement on the Maliana case, I filed a public interest litigation (PIL) before the division bench of the Allahabad High Court on 19 April 2021 with Indian Police Service officer Vibhuti Narain Rai, a former director general of the Uttar Pradesh police.

Our co-petitioners were Ismail, a victim of the Maliana massacre who lost 11 members of his family on 23 May 1987, and lawyer MA Rashid.

In the PIL, we said that more than three decades on, the Maliana massacre case and other custodial killings in Meerut during the 1987 riots had not progressed much since key court papers, including the FIR, had mysteriously gone missing. We also accused the Uttar Pradesh police and PAC personnel of intimidating victims and witnesses into not deposing and asked for either the release of the Srivastava Commission report or the judges to request a copy of the report in a sealed cover.

We also pleaded for establishing a special investigation team (SIT) to look into the events of 23 May 1987, conduct a fair and speedy trial and adequate compensation for the victims’ families. In 2018, after 16 police personnel were convicted in the Hashimpura case, the families of the 42 Muslims killed received Rs 20 lakhs each as compensation because the killings had been carried out by the police. However, since there is no mention of police personnel in the FIR signed by Yaqub Ali, the families of the Maliana victims received only Rs 40,000 each.

After hearing the PIL, Justice Sanjay Yadav, the acting chief justice of the Allahabad High Court at the time, and Justice Prakash Padia ordered the Uttar Pradesh government to file a counter-affidavit. “Taking into consideration the grievance raised in the petition and the relief sought, we call upon the State to file the counter affidavit and para-wise reply to the writ petition,” the order said.

Noted human rights activist and senior Supreme Court lawyer Colin Gonsalves appeared for us in the case. The PIL is still pending in the Allahabad High Court, awaiting the final outcome. Now that the Meerut verdict has acquitted the accused, it is possible the State government will request the court to close the case, but the victims of the Maliana massacre have challenged the verdict of the Meerut Sessions Court in the Allahabad High Court, and the next hearing will be on 14 August.

The author is a journalist who writes in Hindi, Urdu, and English and worked with the BBC World Service. He covered the Meerut riots of 1987 and was an eyewitness to many incidents. The views expressed are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.