The Right to Not Read

Image Courtesy: Deccan Chronicle

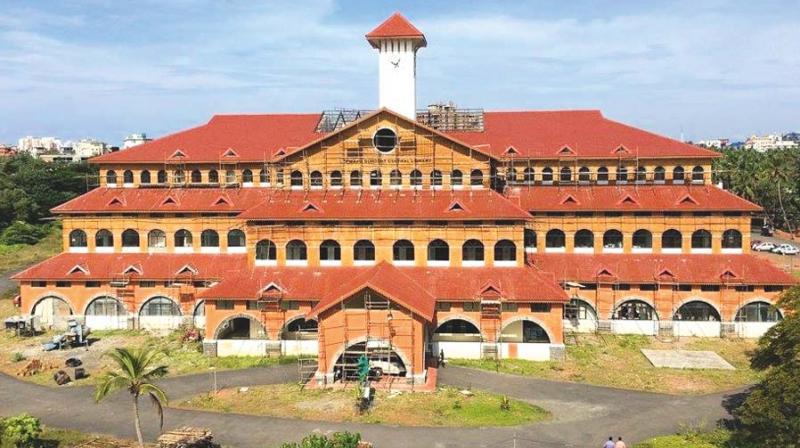

A recent controversy has erupted with regard to the revision of the MA Governance and Politics syllabus at Kannur University. The course is offered only in the Brennan College of Thalassery District in Kerala—the only Indian state governed by the Left.

The proposition of including extracts from Hindutva treatises by V.D. Savarkar, M.S. Golwalkar, Balraj Madhok and Deen Dayal Upadhyaya as compulsory texts for the core paper on Indian Political Thought sparked protests from Kannur University students belonging to a diverse array of student organizations including the Kerala Students’ Union (KSU), Muslim Students’ Federation, and the Students’ Federation of India (SFI).

Kannur students accused the university of saffronizing the syllabus— a charge that the Vice-Chancellor, Ravindran Gopinath, denied outright and referred the matter to an expert committee comprising J. Prabhash (former Pro-Vice Chancellor of the University of Kerala and Head of the Department of Political Science), K.S. Pavithran (former Professor of Politics at the University of Calicut) and A. Sabu (Pro-Vice-Chancellor of the Kannur University). The committee, after reviewing the syllabus, reported that Hindutva texts were given undue prominence in the section on Indian Political Thought and submitted that the curriculum should be so balanced that ‘the pluralism of Indian political thought and ideology’ is properly reflected.

This has drawn a lot of flak from very many respectable liberal commentators who have alleged that this non-inclusion of Hindutva texts in the concerned university syllabus smacks of intolerance. In doing so, they seem to have missed the moot point by a mile. The point is not whether books by Savarkar, Golwalkar, Upadhyaya and Madhok should be proscribed from being read-- book banning and book burning are fascist tactics and serve no purpose really--- but whether they should have the pride of place in a syllabus that is being revised under an elected autocracy on the verge of proclaiming itself as an ethno-fascist state. They presuppose that Indian universities today remain a marketplace of ideas, where, given equal exposure to all ideas and values, truth alone will triumph.

Syllabi-making in today’s India, however, is hardly an innocuous process of letting a hundred schools of thought contend. Ideally, it should aspire to be so, but it really is not.

Syllabi-making is a political exercise into exclusion and prescription. The liberal notion of the syllabi-makers as unbiased adjudicators between contending ideologies is rather naïve. It is never a context-free act and is always fraught with all kinds of problems. Who/what gets included/excluded and when are important questions as is the question of why. This makes reading beyond the syllabus to be the only un-dictated reading and a right of all students. It also implies that the students also have the right to not read texts that are thrust upon them in a curriculum, if they are capable of inciting hatred and bigotry.

It has been argued that a ‘critical reading’ is what we need for it inoculates the readers from hatred and bigotry. This is all very fine but fails on two counts. First, to read a text critically, one does not necessarily have to read it as part of a course syllabus. In fact, the right to not read a text as prescribed in syllabi is more readily invoked by those who have already read the concerned texts critically and by those who have been adversely impacted by the politics of the concerned text in practice. Second, it refuses to consider under what political circumstances certain texts are being prescribed in syllabi.

To not read something as part of a university curriculum in an atmosphere of fear and suspicion, prudery and intolerance, is to perform the important political act of critiquing the syllabus and by extension the state itself. In India, the inclusion of texts in syllabi are also more often than not viewed as tacit sanction by the state: the struggle for political legitimacy is always fought on the turf of education. There is no objective way to make a syllabus, only a balanced way--- not a seesaw game between competing viewpoints but a context-sensitive open dialogue that enriches both the course instructor and her students, whose right to not read emanates from the very right to read critically.

The Hindutva ideologues' texts were not so overwhelmingly represented in Kannur University's MA Governance and Politics course before. They are sought to be introduced in the syllabus now when the political climate in the country has been profoundly polarized by the Hindutva experiment in action.

The liberal commentator’s analogy of critically engaging with Mein Kampf in post-war German schools sounds spurious because Kannur University's revision of syllabus is not happening in post-Hindutva India at all. We are not in that phase of retributive reconciliation yet. India's Nuremberg Trials have not taken place. Criminals of Babri are running the country today. This is much more akin to the making of Mein Kampf an obligatory read for German students in the 1930s and therefore, by invoking their right to not read, Kannur students are resisting and rejecting the ghastly political project of Hindutva.

What these commentators fail to mention is that for any new edition of the Mein Kampf to be legally published in Germany today, it has to be annotated. Otherwise, the publisher will face charges for inciting racial hatred. To do this with Hindutva texts in India at present is absolutely unthinkable. There is simply no comparison. The Mein Kampf in Germany had been out of print for more than seven decades before a critical edition was finally published. This is certainly not true of the Hindutva texts.

Moreover, the argument that one cannot understand Fascism without actually reading Mussolini or Hitler is hilarious because neither of them theorized fascism per se. Fascism has never been a doctrine-centric ideology. Its basic tenet is anti-intellectualism and consequently, it does not even take its own intellectual origins seriously. Germans in the 1930s knew what Nazism was and what it meant not from Mein Kampf but from their experience of living under a Nazi State. Lived experiences need to be considered as equally valid springboards for making epistemic claims, as say, the reading of 'original texts'. And to reiterate, the question here is not about what is being read but what is being prescribed, by whom, where and when, and consequently, the right to not read.

Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, M.M. Kalburgi and Gauri Lankesh have been killed for expressing their thoughts freely in this country. People from specific communities and regions are demonized in mass media and constantly live in the fear of being lynched. All this is happening in consonance with the Hindutva political vision.

For people bearing the real brunt of the violence and discrimination that these texts prescribe, suggesting that they 'critically engage' with We or Our Nationhood Defined is like telling a Jew, Communist, or Homosexual en route to Auschwitz to critically engage with Mein Kampf. Nobody in India at present needs to necessarily read Savarkar and Golwalkar to realize the threat that their disgusting vision poses to their existence and that of the Indian society at large. Maybe some of these liberal commentators do, but that's because the threat is not as palpable for them as it is for the multitude, especially for the minority communities.

Not including Hindutva ideologues in university syllabi at the moment is not an act of intolerance. It is an act of protecting the university and its members who are uniquely vulnerable as political targets of the Hindutva juggernaut. It is an urgent act of creating a bastion against the Hindutva vision. This does involve choosing a side. Protesting students have made a choice in a way our liberal commentators have not.

The battle of protecting the pluralist ethos and constitutional values of India will not take place in Literature Festivals (all very important and enjoyable occasions but politically rather vacuous) where they release books on tolerance but in universities where students would defend their ideas of India that are under siege today. Kannur University students have shown the way by refusing to read the Hindutva ideologues. The question is if we will stand by them.

Suchintan Das is a Rhodes Scholar from India, studying Global and Imperial History at the University of Oxford.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.