Rewriting History: Cinema the New Archive of Power

Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

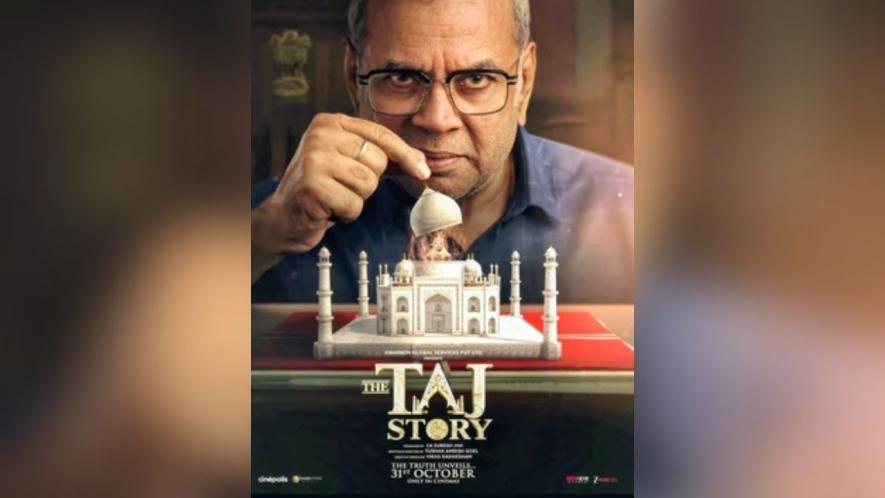

When The TAJ Story, a Hindi film, opened in theatres, it promised to “unveil the truth” behind one of India’s most cherished monuments. What it unveiled instead was the deepening attempt to turn cinema into a political instrument, a medium not as a window into the contemporary, nor for imagining the future, but for refashioning the past. Cinema today has become the preferred weapon for rewriting history. The screen, once a realm of artistic inquiry, is being refitted as an ideological archive where myth passes for evidence and feelings stand in for facts.

Historians are trained to build arguments from evidence and are bound by a discipline that demands verification and integrity. Filmmakers, however, are under no such obligation. Unconstrained by the rigours of research or the ethics of scholarship, they can construct belief out of emotion and turn sentiment into conviction.

The new breed of “historical” storytellers invites audiences to remember selectively, to trade archives for atmospherics and footnotes for fury. In a society saturated with visual media, cinema has quietly become the public classroom of history, a classroom without questions, contradictions, or citations. Millions leave the theatre with a sense of revelation, mistaking imagination for insight and fiction for truth.

Few symbols of India’s composite heritage have been so relentlessly targeted as the Taj Mahal. For years, fringe groups have claimed it was once a Hindu temple, a story repeatedly refuted by courts, historians, archaeologists, and the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). The ASI’s consistent stand is that there is no evidence to suggest the monument predates the Mughal period or was ever anything other than Shah Jahan’s mausoleum for Mumtaz Mahal.

Yet, cinema has been able to convert pseudo-history into visual drama, filmmakers bypass the discipline of proof. A work of fiction can say what a textbook never could and reach millions more. Cinema has become the easiest route to mould collective memory, precisely because it looks like entertainment, not indoctrination. This transformation coincides with the hollowing out of public institutions that once mediated history, universities, museums, archives, even public broadcasting. As reasoned history retreats, film steps in to fill the void, its narrative financed and framed by ideological patrons.

Tax exemptions, state promotions and corporate tie-ups blur the line between cinema and propaganda. The State no longer dictates what can be filmed; it rewards what should be believed. Capital has discovered that ideology sells, controversy markets itself, and nationalist nostalgia guarantees profit.

Films increasingly treat ancient lore as historical evidence, inviting audiences to “reclaim” what colonial or secular historians allegedly hid. The past is recast as a civilisational grievance, and the present as its righteous correction. The simplification is seductive: one community as eternal victim, another as perpetual oppressor. Complexity vanishes; conviction replaces curiosity.

Politics of the Disclaimer

The legal disclaimer, the familiar line, buried in the credits: “This is a work of fiction; any resemblance to real persons or events is purely coincidental”, performs a double duty, it protects producers from lawsuits while preserving the political intent of the story. In theory, it informs; in practice it absolves. Most viewers neither notice nor comprehend the disclaimer’s meaning. A flash of small print cannot neutralise two hours of suggestive imagery.

The disclaimer exists not to warn the audience, but to reassure the financiers. It is cinema’s version of plausible deniability, a way to weaponise belief while disowning responsibility. Films that mythologise history enjoy easier clearances, louder promotion and safer investments.

In contrast, those that question power are quietly defunded or endlessly delayed by the censor board. This alliance between capital, ideology and censorship creates what might be called a cinematic nationalism complex, a system that monetises memory and manufactures consent, one spectacle at a time.

Who Loses When History Is Tinkered With?

The loss that follows is not merely factual; it is civilisational. When falsehood is repeated as faith, the line between memory and myth disappears. The coming generations grow up believing that everything was, and therefore must always be, fine. They inherit pride without introspection, and identity without understanding. In that comfort of imagined perfection, the will to learn and the courage to correct are quietly extinguished.

For those whose histories are rewritten, the loss is far more brutal. The vilification of minorities, and those at the fringes, through such retellings, robs them not only of recognition but of belonging. It negates the centuries of struggle through which they claimed their rightful place in the story of India. To be erased from history is to be exiled from memory and once exiled, to face suspicion in the present.

When a film propagates the message that the Taj Mahal was once a temple, it does not simply misinform; it distorts the moral fabric of history itself. Historians and the ASI have repeatedly and unequivocally refuted such claims, but cinematic spectacle rarely depends on truth. It depends on emotion and emotion, once politicised, becomes an instrument of persuasion.

When power rewrites history to suit its image, the result is not national pride but national amnesia. The story may glitter on screen, but what fades is truth and with it fades the conscience that allows societies to grow wiser through remembrance.

What cannot be overlooked is the fact that amid this orchestrated amnesia, another cinema lives, one that treats history as debate, not destiny. Regional and independent filmmakers continue to recover buried voices, re-humanising what official narratives dehumanise. Court, Kaathal – The Core, and All That Breathes remind us that truth is never singular, and that dissent, too, is heritage. These works reach fewer screens but speak to a deeper democracy, the right to remember freely.

Reclaiming the Right to the Past

To reclaim cinema is to reclaim citizenship. We need investment in independent film, diversity in film education, and strong public institutions that protect scholarship from ideology. Most of all, we need viewers trained to read critically to question what is shown, and to notice what is omitted. A historically literate public is the best defence against the cinematic rewriting of reality.

A nation is what it remembers. When the State outsources memory to the marketplace of myth, history becomes a hostage. If we continue to accept fiction as faith, we will soon find that our heritage has been rewritten, beautifully shot, legally disclaimed, and widely believed. The question is not who built the Taj Mahal, but who is rebuilding the story of India, one frame, one film, one disclaimer at a time.

Shirin Akhter is Associate Professor at Zakir Husain Delhi College, University of Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.