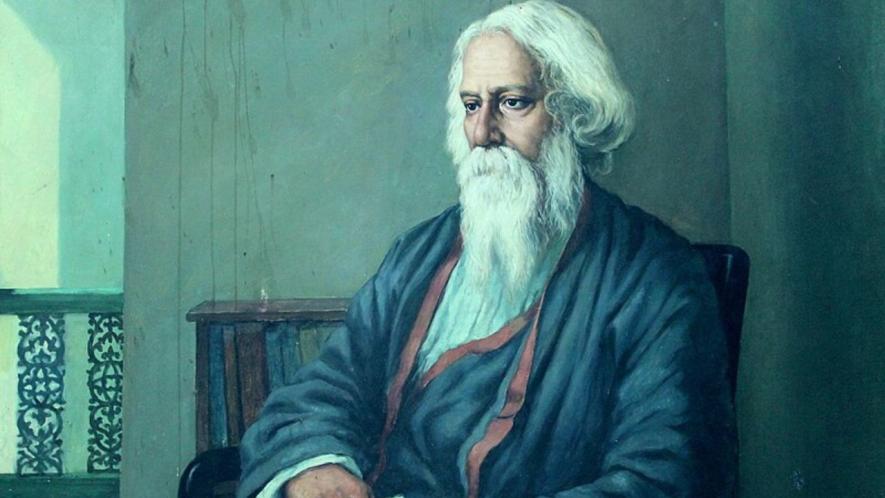

Rabindranath Tagore: An Internationalist Patriot

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Rabindranath Tagore was a full-time patriot, probably a more intense one than many of his contemporaries. He was one of the firsts to realise that the strength of our country did not lie in vain shrieks of national pride: it lay in the ability to turn the gaze inward, while widening the horizons of the mind beyond the parochial boundaries of the nation-state. His patriotism was an exercise in composed courage, not rabid aggression.

In our baleful times, Tagore's universal humanism can very well serve as a strong intellectual rejoinder against narrow aggressive nationalism espoused by the current ruling dispensation. He understood that nationalism is a sentiment based not on the positive will of a people to progress, but on insecurities about themselves. For him, only an insecure group of people would feel the need to malign other countries in order to feel better about their own selves, or, for that matter, need national heroes to look up to. This feeling of fear and insecurity created a kind of blindness which rendered itself as the "best malady of nationalism". Thus, he puts much stress on the need to free the mind of fear.

Any sort of blind following of a certain ideal was a dangerous prospect for him. For instance, in Tagore's Home and The World, Nikhilesh refuses to bow down to the nation and worship it as the Mother, since he is unable to uncritically put an abstract entity like the nation on a higher pedestal than his fellow humans. Apart from being a strong expression of humanism, Nikhilesh's hesitation toward the slogan of "Bande Mataram" can also be read as a complete rejection of any sort of "Vandana" or worship which is external to one's own self. To Nikhilesh, the Swadeshi movement had to be constructive, and opposed meaningless burning of foreign cheap clothes which were mostly used by the poorer sections of the society.

Tagore's unflinching commitment to non-dualist philosophy also had a role to play in the framing of his politics: a set of ideals based on critical self-introspection and free thinking, rather than rugged tiptoeing behind authority.

Love for the country could never come from a position of servility and fear. For Tagore, love could only swell from inner strength. He understood that just by virtue of being born in a country, one does not automatically become a true national. One had to earn that right through selfless love for their fellow countrymen. In a brilliant excerpt from Desher Kaaj (Duties Towards our Nation), the reader can witness this for their own:

"We are foreigners. Only by being born in a country, we can't call it our own. As long as we don't know it, or don't win it through our inner strength, the country is not ours. We haven't won the country ourselves. There are many non-living, inert entities, and we are their neighbours. Just like the country doesn't belong to these objects, it doesn't belong to us, too. This inertness is known as delusion. The one who is deluded is an ever-foreigner. He doesn't know where he is. He doesn't know who he is truly connected with. One can never realise their true potential through external support. Nobody else can give my country to me. Only when I can know my country as my own, with all my heart and soul, will it become mine. When I realise that my nation's life is my own life, I will be back home. When people of my country are dying of hunger and disease around me, it would be my utmost stupidity to shout patriotic slogans on a stage while putting the blame of such disaster on others." (translated by the author)

This inclusive vision of patriotism was imbued in internationalism. A prophet of world peace, he had travelled to more than 40 countries, and forged bonds which often went beyond the formal. In an age preceding lightning-fast communication, Tagore regularly kept himself updated with what was happening in other countries. These concerns were never diplomatic. Rather, they had their source in his deep interest in cultures other than his own. He became interested in "cross-cultural interactions" almost a century before the present-day academics found it fashionable.

In Travels in Persia, Tagore writes extensively on the long history of Indo-Persian cultural exchange, and how the shared past between the two peoples made him feel at home in Persia. Also, as an educationist, he felt that it was imperative for his students at Vishva Bharati to learn about foreign cultures along with their own – and opened the first Chinese, East Asian and West Asian Studies Departments in the country. The slogan for his experimental university was "Confluence of the West and the East", which aptly serves to showcase Tagore's conviction towards the internationalist cause.

His spiritual ideas about oneness of all can also be said to have coloured his internationalist cause. He says in his Oxford lectures titled The Religion of Man: "The real tragedy, however, does not lie in the risk of our material security but in the obscuration of Man himself in the human world. In the creative activities of his soul, Man realises his surroundings as his larger self, instinct with his own life and love. But in his ambition, he deforms and defiles it with the callous handling of his voracity."

I would like to read this rather esoteric excerpt about the pitfalls of dwelling too much in the material world as a warning against parochial national divisions. The goal for humans was to attain the realisation of "his surroundings as his larger self, instinct with his own life and love." If considered on an international scale, this could also be taken as a claim for international solidarity: a single nation's destiny cannot be cordoned off from the destiny of the world surrounding it. In the next sentence, Tagore exclaims that "in his ambition he deforms and defiles it with the callous handling of his voracity".

Although he refers to the 'ambition' to accumulate more wealth here, this can also be read as indicative of hyper-nationalist ambition, which he saw unfolding into expansionist desires in front of his eyes. He critiqued Japanese military expansionism in his own times. He sincerely hoped that the coming together of people from different cultures could significantly lessen the lust for more territories and the hunger for world domination.

The fascists of our times, just like their predecessors, consider such ideas weak and feminine. A true nationalist, in their eyes, would be someone who would wilfully surrender their critical sensibilities at the feet of the abstract Nation and obey a demagogue without questions. They would always point fingers at some imagined enemy – internal or external – for weakening their glorious nation. They would always be fearful of conspiracies being fomented against their motherland, either by some foreign country/agency or anti-nationals within the country. Their foremost duty as proud nationalists would be to protect the nation from such predicament.

However, Tagore would possibly have left a few deep breaths – dirghosshash as we call them in Bengali – looking at them. Thank heavens that the fascists do not read him. If they did, they would have him dragged to jail from his ashes.

The writer is a post-graduate from the Department of History, University of Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.