Oldest Ever Genetic Data Recovered from Ancient Human who Lived 2 Million Years Ago

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Scientists have recently reported about extracting genetic information from an ancient human relative that lived around two million years ago. This has been said to be the oldest of such data. The genetic information is from the African hominin named Paranthropus Robustus. The findings are reported in the preprint server Biorxiv.

Hominins signify modern humans, extinct archaic humans, and their immediate ancestors. Paranthropus Robustus is a hominin species that lived 1.2 to 2 million years ago in present day South Africa.

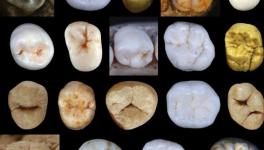

The Biorxiv research findings of the genetic information about the hominin species were extracted from proteins found in several tooth fossils in a cave in South Africa. The latest study conducted by a research team led by Enrico Capellini of the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, sampled four teeth belonging to the P Robustus collected from the Swartkrans cave in South Africa, 40 kilometres from the capital city of Johannesburg. The team of researchers used the technique known as mass spectrometry to analyse each of the proteins they found in the teeth' enamel (the mineral's outer layer). With the technique, they could decipher the amino acid sequences of the proteins.

All proteins are made up of amino acids (building blocks of protein) present in a particular sequence, just like the alphabet in a word. The proteins differ from each other in the sequences of these amino acids. Knowing the amino acid sequences, scientists can then proceed to analyse the relations amongst various proteins—similar sequences indicate closely related proteins.

The team found a protein called amelogenin-Y in two of the samples. This protein is a product of a gene found on the Y chromosome, which is a determinant of sex. This protein's presence helped the team conclude that the teeth samples belonged to males. The proteins were attributed to the X chromosome in the other two of the teeth, which is also a sex determinant. From this, the researchers conclude that the other two teeth belonged to females.

In total, the team sequenced 400 amino acids, and with the help of it, they could build an evolutionary tree. The evolutionary tree suggested that the P Robustus is distantly linked to Homo sapiens. In fact, they found that Neanderthals, Denisovans, the other extinct archaic humans and H sapiens are more closely related to one another than to P Robustus.

Evolutionary trees depict the evolutionary relationships among different proteins. This relationship of proteins can further demonstrate the evolutionary relationship of the different species that they belong to. Proteins are more resilient in comparison to DNA, and extracting genetic information from very old fossils from protein remains can be more helpful.

Moreover, producing an evolutionary tree from genetic data may further help understand the position of other hominin species, like the Lucy (whose complete specimen is available) or the Australopithecus afarensis (whose fossil fragments are available) in the hominin family tree. This still remains a big task.

However, there are differences of opinion on whether such protein samples will really help in bringing more clarity to the hominin evolution. In the latest research, the team found proteins in the teeth of P robustus that are less variable, which appear to be less informative in constructing the tree.

It is thought that as the genetic data reported in the Biorxiv paper is the oldest that has been collected from any hominin, it may appear helpful in tracing back genetic records to times and places that were not thought previously. It is worth mentioning here that scientists have long debated P Robustus and its relation to other ancient human species.

However, for some experts, it is still not very clear how the few protein sequences recovered from the old fossils would help reveal the long-debated evolutionary relationships. This is reflected in the comment of Beatrice Demarchi, a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Turin, Italy. Demarchi was quoted in an article about the findings by Ewen Callaway published in Nature, saying, “Nobody really knows yet how useful this will be.”

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.