Odisha: Delayed Rehab Funds, Scarce Jobs Push Rescued Workers Back to Bonded Labour

Kumari Bag with her husband at her residence in Jhaankripali village of Balangir district. Photo by Aishwarya Mohanty.

Balangir/Kalahandi: In October 2018, Kumari Bag, her husband, and their minor daughter migrated to Karnataka to work at a brick kiln, leaving her previous job at a poultry farm in Raipur. The allure was a promise of significantly higher wages at the brick kiln – double of what she had been earning. However, what seemed like a lucrative opportunity for a better future soon turned into an unending cycle of exploitation and bondage.

Yet, the Bag family's predicament is not unique. Each year, thousands of individuals from Odisha, especially from the Kalahandi-Balangir-Koraput (KBK) region, migrate to Southern states to engage in bonded labour at brick kilns.

Kumari Bag lives with her husband and six children. She has been rescued twice from bondage in brick kilns and still awaits rehabilitation assistance. Photo by Aishwarya Mohanty.

The Bonded Labour System was legally abolished throughout India on October 25, 1975, through the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Ordinance, later replaced by the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976, but modern slavery persists in various forms.

Only a fraction of labour migration is documented through registered contractors. Over time, both state and Central governments have attempted to address the situation, cracking down on traffickers and registering workers and contractors. Nevertheless, the problem persists, with numerous families forced into remigration even after being rescued from inhumane conditions. Many of these families belong to dalit and adivasi communities.

The Endless Wait for Rehabilitation Funds

In 2019, Kumari and her husband were taken to Kondasethihalli village near Bangalore to work at a brick kiln. A local contractor, also known as 'Sardar,' provided them each with an advance of Rs 30,000. Although the contract was initially for six months, they were coerced to stay well beyond that period, enduring harsh conditions while toiling at the kiln. The workday began at 3 am and lasted until noon. After a brief hour-long break for lunch and rest, their work resumed. Living under a tarpaulin sheet, they prepared their own meals and faced threats for any work-related lapses.

However, the situation escalated when Kumari fell ill with a high fever and was brutally beaten by the owner for failing to work. Weeks later, she and her fellow workers were rescued from the kiln and they returned to their villages. They received an initial compensation of Rs 20,000 from the Karnataka government, along with a certificate declaring their release from bondage.

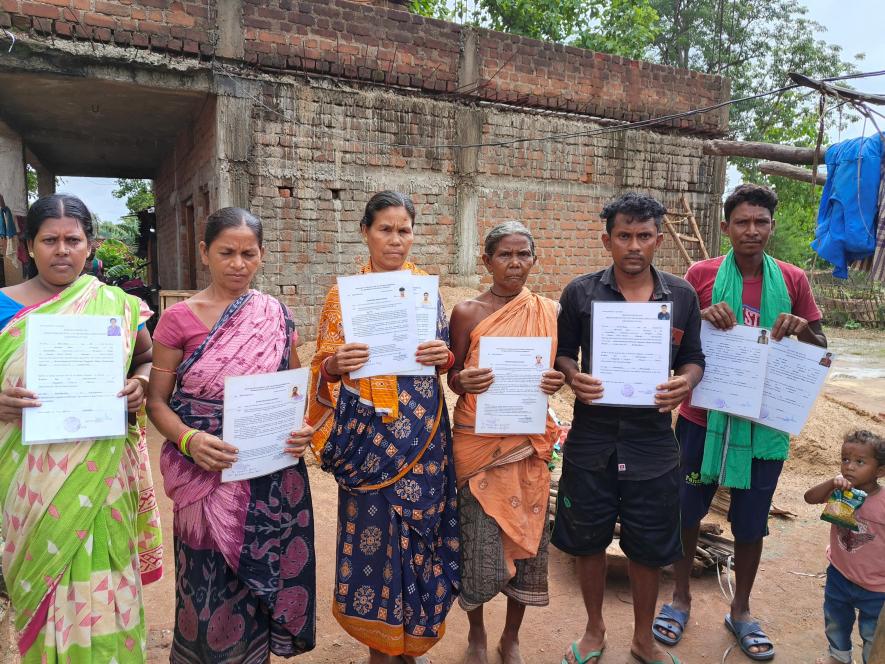

Rescued workers from brick kilns are issued a certificate stating that they are now free from "bondage" and a relief assistance. Photo by Aishwarya Mohanty.

Beyond this initial compensation, rescued bonded labourers are entitled to higher rehabilitation assistance. Revised in 2016, this assistance amounts to Rs 2 lakh for women and Rs 1 lakh for men, with an additional Rs 3 lakh for those rescued from brothels or sexual exploitation (women, children, and transgender persons). However, the release of this assistance is tied to the conviction of the accused captor, leading to delays. Coupled with a lack of livelihood opportunities in their village, this delay compels them to remigrate in search of income.

"When I first returned, I believed I would never go back to that exploitative space. But I was mistaken," Kumari said. She lives with her husband and six children in a small, one-room kitchen house. A landless dalit family, they rely on farm labour and sharecropping during monsoons, providing income for only four months a year.

In a desperate situation once, Bag undertook the journey herself and received an advance of Rs 20,000. “The advance is used up for one or the other emergency. We have no land of our own. In years with scant rainfall, we have no farm work either. When we approach anyone for work, the only people who assure us both work and money are these contractors,” she says.

The family lacks a job card, depriving them of employment opportunities under the MGNREGA scheme. They also haven't secured a ration card. With limited housing space, their daughters sleep at relatives' houses.

Lalita Tandi (40), a native of Phatamunda village in Balangir’s Saintal block, was rescued with 200 others from a brick kiln in Hyderabad, in 2014. She initially received only Rs 1,000 in compensation. Nine years later, she still awaits rehabilitation assistance.

"All my details were recorded, and we were promised the money. Yet, it never materialised. The Rs 1,000 that I received were spent within days. While we understand that returning to the kiln is like facing death, do we have other choices?" she told this reporter.

In Kalahandi’s Padampur village, 45-year-old Nila Sabar was rescued twice from a brick kiln within four years. As the father of four daughters, Sabar worked at the kiln to secure a lump sum for his daughters' marriages. "I had to marry off my daughters. My eldest son-in-law received a bike as part of a dowry. How was I to arrange such funds? The Sardar gave me Rs 30,000 upfront. The wedding was successful," he said.

Nila Sabar of Kalahandi district resorts to working at brick kilns to arrange money for his daughter's wedding. He has four daughters. Photo by Aishwarya Mohanty.

While working at the kiln, Sabar faced beatings, sleep deprivation, illness, and a longing to return home. The death of a young boy who fell into a furnace led to their rescue. Despite his hesitations, Sabar chose to remigrate for his second daughter's marriage.

Months later, he and 100 others were rescued again. However, after both rescues, he still awaits his monetary assistance.

According to activists working on the ground, there is a lack of coordination between the departments concerned and the victims, which only further delays the process. “In most cases, there is no follow-up by the department officials. Even the villagers are unaware of who can be approached and when. They won't be following their cases up to conviction anyway. This gap in coordination deprives them of their assistance,” an activist working with rescued bonded labourers in the region told this reporter.

When contacted, district and state labour officials said rehabilitation assistance was supposed to be released by the Panchayati Raj Department. They lacked data on the number of rescued bonded labourers awaiting assistance. The Panchayati Raj Department also failed to provide data, citing its dependence on convictions.

Notably, on June 23, 2023, the Odisha Human Rights Commission directed the Panchayati Raj Department to report the status of bonded labourers in Odisha.

Lack of Local Support, Livelihood Opportunities

Under the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976, the identification, release, and rehabilitation of freed bonded labourers are the direct responsibilities of the concerned state government/Union Territory.

As per the Union Ministry of Labour and Employment, in 2018, as many as 51,441 bonded labourers were identified from Odisha, the third highest in the country.

The Central scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourers 2021 also states that rescued individuals should undergo skill development programmes for effective rehabilitation. As per government data, between 2016 and 2021, a total of 11,616 rescued workers in the country were provided assistance of Rs 1,197.55 lakh.

As per the rehabilitation rules, a state government is also obligated to survey bonded labourers once every three years in sensitive districts, allocating Rs 4.5 lakh per district and involving non-government organisations (NGOs).

"We haven't received any skill development training. Opportunities are scarce. After the rescue, we're left to fend for ourselves. Desperate for income, migration seems like the only option. My sole skill is brickmaking. Back in the village, I try to make and sell bricks at reasonable prices," Memraj Sabar (33) from Nuagaon gram panchayat in Kalahandi district, told this reporter. The alternative, MGNREGA (the rural job guarantee scheme), also falls short of ensuring sufficient workdays.

Memraj Sabar, a native of Nuagaon in Kalahandi makes bricks back at his village and sells them locally. He took up this work after being rescued from a brick kiln and unable to find any work near his village. Photo by Aishwarya Mohanty.

When Nila was rescued from Tamil Nadu in 2021, he sought work under MGNREGA in the village. Despite the state government's promise of 300 workdays, he received only 12 days of work.

"For villagers to benefit from the rural wage scheme, there must be ample work available. After 12 days, I was idle again. What can we do in such situations?" he said.

Sukant Sethi, Labour Divisional Commissioner of the zone, told this reporter, “We have improved our preventive rescue measures while they are being taken for work. We are also working on multiple avenues to help them secure a dignified income here in the state rather than migrating out. The first aspect is better irrigation to make agriculture a perennial source of income.”

Aishwarya Mohanty is an independent journalist based in Bhubaneswar, Odisha. She writes on gender, climate change, rural issues, and social justice.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.