Nobody Killed Muslims

A lot has happened to words over five years of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in power. Many once-commonplace words—democracy, secularism—have gathered new meanings. A few words have lost their universally-accepted meanings to embrace new ones, such as josh or tukdey-tukdey. Words that had gone out of usage have been reintroduced to the lexicon as well: lynch mob, for example.

Words such as democracy and secularism inform the foundational ethos of Indian constitutionalism. They now have been made to wear a pall of sarcasm. Hurling these words as barbs, often after tweaking how they are spelled or pronounced, is a recurrent feature of public discourse.

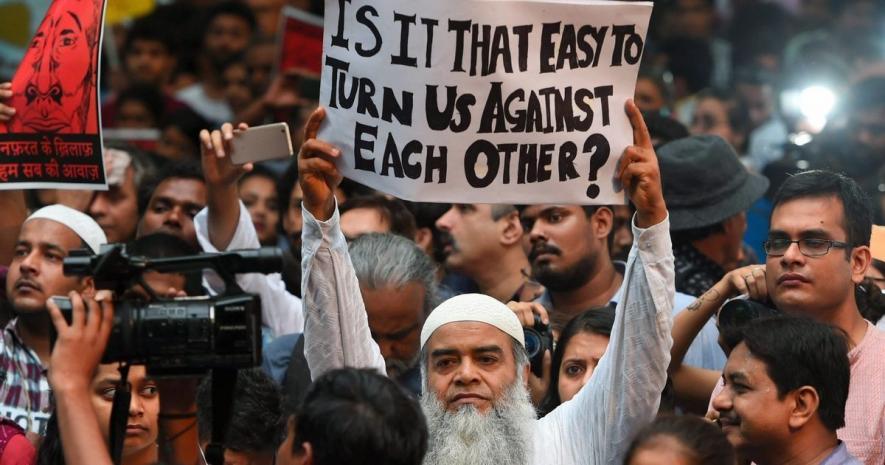

Josh, which normally implies energy, now means nationalistic bravado. The alliterative phrase ‘tukdey-tukdey gang’ has joined ‘Khan Market gang’. Both are central to the current political discourse. A wild-card entry is ‘lynching’. This word now carries on its shoulders the weight of 50 bodies, a tally that the nation started keeping after 2014.

The dictionary says that lynching is killing someone over a transgression without a legal trial. In today’s context, it is a metaphor of brutal ‘othering’ and denied visibility. Lynching is always a public spectacle, for without spectacular visibility the act it describes cannot have the chilling effect it seeks. Lynching is a celebration, a macabre festival of dehumanising the ‘other’.

In the modern world, lynching first gained sanction in the United States, where from 1870 to 1930, a spate of killings took place of African Americans. The book, Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photographs in America, compiles a series of essays and photographs discovered by the collector, James Allen. This “extraordinary legacy of photographs and postcards taken as souvenirs at lynchings throughout America” published by Twin Palms Publishers explains how taking a photograph of a lynch mob’s killings or making postcards of them had become part of America’s white-supremacist culture in those days.

In India, cow protection gangs and their patrons video-record lynchings and propagate them via WhatsApp, YouTube channels and other social media, where they can be consumed in large numbers. Their consumption supplements the masculine hyper-nationalist anxiety that has gripped large sections of the population.

‘Imaginary’ Fear

The phenomenon of lynching has been complicated by recent lexical somersaults made by the Prime Minister. It would not be a stretch to say that lynching, in the New India he has imagined, is regarded as an “imaginary fear”.

In his inaugural address at the Central Hall of Parliament this year, the Prime Minister said, “Due to vote bank politics, minorities were crushed, boxed into a corner, subjected to imaginary fears, and exploited during the elections,” he said. He then appealed to Bharatiya Janata Party workers to “win their trust”. Ostensibly, this was an acceptance of their mistrust of his party.

Thus, the frightened and violated face of Tabrez becomes nothing more than a metaphor for an imagined, or imaginary, series of lynchings. This vocabulary strips the community of their rights to even claim that they are vulnerable.

Contrast this so-called imaginary fear with the Hindutva project to instil real fear among citizens regarding Muslims. For instance, it is being propagated that Muslims would soon outnumber Hindus in India. Simultaneously, India is being projected as a land that belongs primarily, if not solely, to Hindus. This project has gained momentum over the last few years. Arjun Appadurai’s significant work, Fear of Small Numbers, unpacks the “anxiety of incompleteness” and how it leads to a fear of minorities.

In a liberalised economy the nation-state retreats from asserting its economic sovereignty. The only way it can establish a sense of nationhood is to assert cultural sovereignty. The nationalism project is such that it has injected the imagination of citizens with a national identity that is ridden with anxieties.

This anxious condition makes citizens feel that Muslims are deterring a larger shared project for a ‘pure’ nation. To successfully sustain such a project, an imaginary threat from the ‘othered’ community is necessary. This is the “real” (read, legitimate) fear that contradicts what Modi calls ‘imaginary fear’.

Legitimising Fear

Legitimisation of the fear of minorities does not require prior evidence. The hate campaigns of the Sangh Parivar and BJP leaders embed the fear of a growing Muslim population in the minds of the Hindu populace. Claims of historical deprivation made by Hindutva forces, coupled with their pledge to rescue the glorious past of the country, outrightly reject Muslim’s rights for equal citizenship.

Hence, even the right to be afraid is appropriated by the majority community. For them the “real” past has been transformed into a story of invasions by Muslims and nothing else. This facilitates the appropriation.

Construction, Reconstruction, Deconstruction

The meaning of lynching needs to be reconstructed in order to deconstruct the fear that engulfs the Muslim identity in New India. How do we conceive of lynching when large-scale orchestrated communal violence is absent? Is the fear of being lynched actually “imaginary”?

The Constituent Assembly debates offer some clues: In these debates, political safeguards for Muslims and Sikhs in the form of separate electorates were viewed as a colonial political ploy to divide and rule. Besides, the security of the socially and economically backward sections was taken into consideration but the Muslim question was deprioritised.

Rochana Bajpai in her 2000 paper, Constituent Assembly Debates and Minority Rights, published in the Economic and Political Weekly says, “The dominant opinion usually conceived the nation in terms of biological metaphors. For instance, as an organic whole, a body politic, a natural entity—whereas minorities were artificially created. Minorities were referred to as ‘disfigurements’, ‘cancerous’, ‘poisonous’ for the body politic. Minority safeguards in such utterances were referred to variously as privileges, concessions and crutches.

Muslims were told not to feel distinct from the larger community. As Vijayalakhsmi Pandit told the Assembly, “If the larger interest suffers, there can be no question of real safeguarding of the interest of any minority.” Thus, mitigating political safeguards came along with allegations of Muslim appeasement.

The first agriculture minister of Independent India, PS Deshmukh, said while addressing the debate, “Rather than tyrannise the minorities, the fact was that in most places the minorities tyrannised the majority. The Muslims have almost everywhere enjoyed privileges far in excess of what may be called just and fair.”

Such debates, when followed carefully, show how the image of a “tyrannical” Muslim minority was constantly reproduced.

Political safeguards for religious minorities in the newly born secular country were not seen as imperative. The steep decline in representation of Muslims in Parliament over the last four decades contradicts this narrative. For instance, the lower house of Parliament now has only 27 Muslims out of 545 MPs. None of them belong to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

Spatial Encroachment: Denial of Religious Rights

Muslims were given cultural rights to practice their religion. However, during the late eighties, the emergence of militant Hindutva directly hit these rights. The primary objective of the militant Hindutva outfits was to conduct a kind of spatial encroachment. Popular history was tweaked by them to fit the Hindutva imagination of Muslims as invaders, outsiders, aliens, strangers and thus liable to be punished and removed from the space.

Sociologist Satish Deshpande has aptly termed this socio-spatial project of communalism as “competitive de-secularisation” or the denouncement of the rights of one community in a secular democracy by another, which then claims its own right to secularism.

De-secularisation shows up in regional and national contexts across India. On the one hand, it ended up with the demolition of the Babri Masjid and on the other it reflects in the organised movements run by Hindutva outfits, such as the one to hoist the national flag at Idgah Maidan, Hubli, Karnataka.

Attempts to deny Muslims their religious rights resulted in widespread communal polarisation. That polarisation, in turn, triggers violence against them in riots. Lynchings are, therefore, a part of the sliding scale of intensity of terror and violence inflicted on the Muslims.

The perceived threat from Muslims relegates them to the category of sub-humans. Historian Tanika Sarkar’s work on post-Godhra violence in Gujarat records that the perpetrators burned the dead in order to “desecrate Muslim death by denying them an Islamic burial”.

Apart from the desire to alter the urban landscape spatially, the communal riots that erupt every decade in India stand for brutality and dehumanisation—the entire semiotics of terror.

Lynching and New India

Unlike systematic communal violence, the strategy behind lynching has no spatial dimension but retains its spectacular orchestration. That is why lynching is mechanically reproduced in video recordings. Justifications for the act, such as the accusation that the victim had possessed beef, furthers the impunity. The reproductions hark back to the lynching postcards popularised in the United States.

The discourse of religious (as against political) rights has been reduced to “cow protection” and slogans like Bharat Mata ki Jai and mocking the foundational values of the republic by twisting, secularism to ‘sickularism’ and so on. For this dynamic to work it is also essential to project the forensic report of animal flesh as more valuable than the body of a victim of lynching.

New Patterns of violence

Earlier lynching was based on allegations of transgressive behaviour such as dietary preferences or the refusal to chant slogans such as Bharat Mata ki Jai. In recent cases, just being Muslim is enough for a lynch mob, which includes having a ‘Muslim’ name or wearing a skull cap. The killing of Tabrez Ansari is testimony to this. The desire to eliminate any mark of Muslim identity is a form of forcible and deliberate invisibilisation.

The ‘imaginary fear’, therefore, is about side-lining and invisibilising the ‘real fear’ that Muslims are living with. The arc has gone from denial of political safeguards by encroaching on Muslim religious sites to completely denying visibility.

Unless democracy and secularism are redefined, words such as lynching will not be effectively buried. For this to happen, the real fear of the minorities must be taken into account first and no longer deemed imaginary.

The writer is a PhD Scholar at the School of Liberal Studies at Ambedkar University and is working on systematic exclusion and spatial segregation of Muslims in Jharkhand.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.