Muslims and Mental Health: Talking About Discrimination and Violence

Image Courtesy: The Indian Express

“It does not matter if we have a stable job or not, if we are economically independent; the fear of getting arrested purely due to our religion never stops.” — Khadija from Murshidabad.

“My past experiences with a mental health practitioner were unproductive and mentally tiring. If the people who are supposed to help us do not understand the oppression we face, how will we ever be able to share our uncertainties in a non-judgmental setting?”—Javed from Bhopal.

Khadijha and Javed, and many like them, crave a safe space to voice the daily and multiple injustices and discrimination they face. They needed to communicate their anxieties freely.

In India, over the last few decades, there have been relentless assaults on the rights of minority communities and oppressed castes. But little or no attention is paid to the state of mental health among members of these communities. No studies have been conducted to analyse the correlation between the state’s actions and the effect it has on the mental health of the Muslim community.

In an effort to reach out and create a safe space for Muslims to speak out, Bebaak Collective organised a discussion with people from eight states, between 8 and 22 September. The discussions were eye-openers. People from all over the country communicated their struggles in the current climate, and how much emotional impact it has had on them. Several participants expressed how connected they feel in a space that did not seek to isolate them, and related to what they had to suffer through instead.

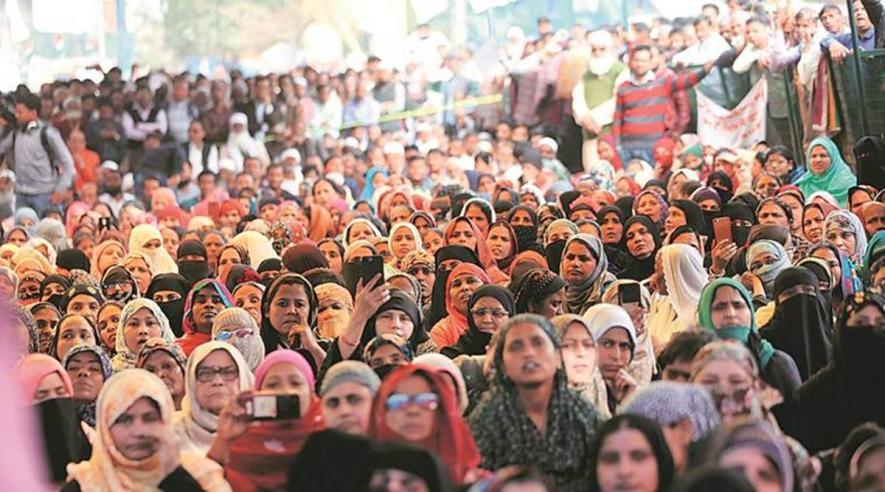

Although India is a secular country, the discrimination and deprivation that the members of the Muslim community face here is well-documented. The recent Shaheen Bagh protest verdict is a prime example of the manner in which the Muslim community suffered at the hands of the state through a number of policies and laws. The protest, which drew Muslim women from all over India, was monumental and unprecedented. Muslim women, who face religious as well as gender-based oppression, came together to protect their rights and protest the discriminatory Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019. Even after being relentlessly threatened, they protested; many stepping out of their homes for the first time.

However, the state prohibited public disturbance or blocking of streets during a protest, completely overlooking the concerns of the minority community and instead addressing just the “inconvenience” that the unaffected public would face. Every time the marginalised come forward to speak for their community, they are repressed by authorities and booked under draconian laws such as the UAPA. There were many instances during the anti-NRC protests and the violence in Delhi, where Muslim activists, academics and youth were discriminated against and even targeted by police.

This systemic oppression, simply due to their Muslim identity, has negatively impacted the mental well-being of the community.

Where are the voices of Muslim women? How long will we allow Islamophobic men to make our decisions for us? When will the state recognise our cognitive autonomy? These questions are on the minds on Indian Muslims as the situation unfolds, and worsens, before their eyes.

The continuous lack of justice and incarceration of community leaders have left Muslims in a constant state of frustration and fear. They have no outlet to vent their worries. The state has created a situation where the community feels completely isolated from the rest of the country. Something as trivial as forwarding a message that is critical of the government is looked upon as “anti-national”. All such incidents have immensely impacted the community’s mental health.

Given the harsh economic situation in India, for a majority of citizens, accessing mental health services has become a privilege rather than a medical necessity. The situation is exacerbated for a significant proportion of Muslims who are not financially secure. Besides, other structural barriers hamper their ability to afford quality mental healthcare. In a report by the National Statistical Office, it was revealed that the literacy rate for Muslim women in India was lower than women of any other religion. Muslims also have the highest proportion of youth (three to 35-year-olds) who have never enrolled in formal education programs. These barriers limit the community’s opportunities to gain formal employment, and thus many end up getting stuck in the cycle of poverty.

Even those Muslims who can afford therapy end up facing new obstacles. The mental health industry often operates from a space of neutrality while trying to make a diagnosis and provide an intervention. However, it fails to recognise the mental stress that comes from institutionalised structures of oppression on minorities. By calling itself “neutral”, the industry ends up hiding its Islamophobic and anti-caste mindset. Often, mental health practitioners tend to focus on the classification of a given mental condition, and do not explore the psychosocial causes behind them.

As Javed experienced, psychologists often fail to recognise the struggles that derive from belonging to an oppressed group. They often find their issues being undermined—as if medication is the only solution to their problem. Javed had to repeatedly explain his frustration with the discriminatory policies, but he confronted a wall when the psychologist refused to “make their sessions political”. In this way, the therapist’s chambers did not provide a safe space to Javed to communicate his worries.

It is essential to start having important political discussions as we attempt to provide marginalities with much-needed community care. Until mental health practitioners understand the vast struggles that the Muslim community faces, many from the community will refuse to seek help. We learned during our interactions with Muslim community, that while they wish to talk about their traumatic experiences, they are also hesitant to do so. They want to share their experiences of the stress caused by state-sponsored policies and social discrimination. Yet, they fear that the state and its supporters will exploit their vulnerabilities if they reveal them. However, to break the stigma against talking about mental health, we will need to start observing, accepting and working towards the injustice that the minorities have been facing, and provide them with better mental healthcare.

The authors are members of the Bebaak Collective. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.