Milada Ganguli: A Czech Woman Who Archived India’s Tribal Soul

Milada Photo from Parthajit Gangopadhyay

In the summer of 1939, as Europe teetered on the edge of World War II, a young woman from Czechoslovakia began a journey that would define her life, and bridge two distant worlds.

Milada Ganguli, born Milada Sýkorová, left her homeland and moved to India after marrying Bengali writer and orientalist Mohanlal Ganguli. What began as a personal migration soon transformed into a lifetime of cultural discovery, academic inquiry, and deep empathy for India's indigenous communities.

Milada was born on July 10, 1913, in the Czech town of Přerov. She met Mohanlal while studying in London, where her interest in India began. But no academic course could have prepared her for the vibrant, chaotic, and layered reality she encountered in India.

After settling in Calcutta, she met the legendary Tagore family. Her relationship with Abanindranath Tagore—a painter, writer, and Mohanlal's maternal grandfather—deepened her appreciation of Indian aesthetics. On the sunny verandahs of the Thakurbari, she listened as Abanindranath told her stories of India’s myths, symbols, and art. These early encounters laid the foundation for her long engagement with Indian culture.

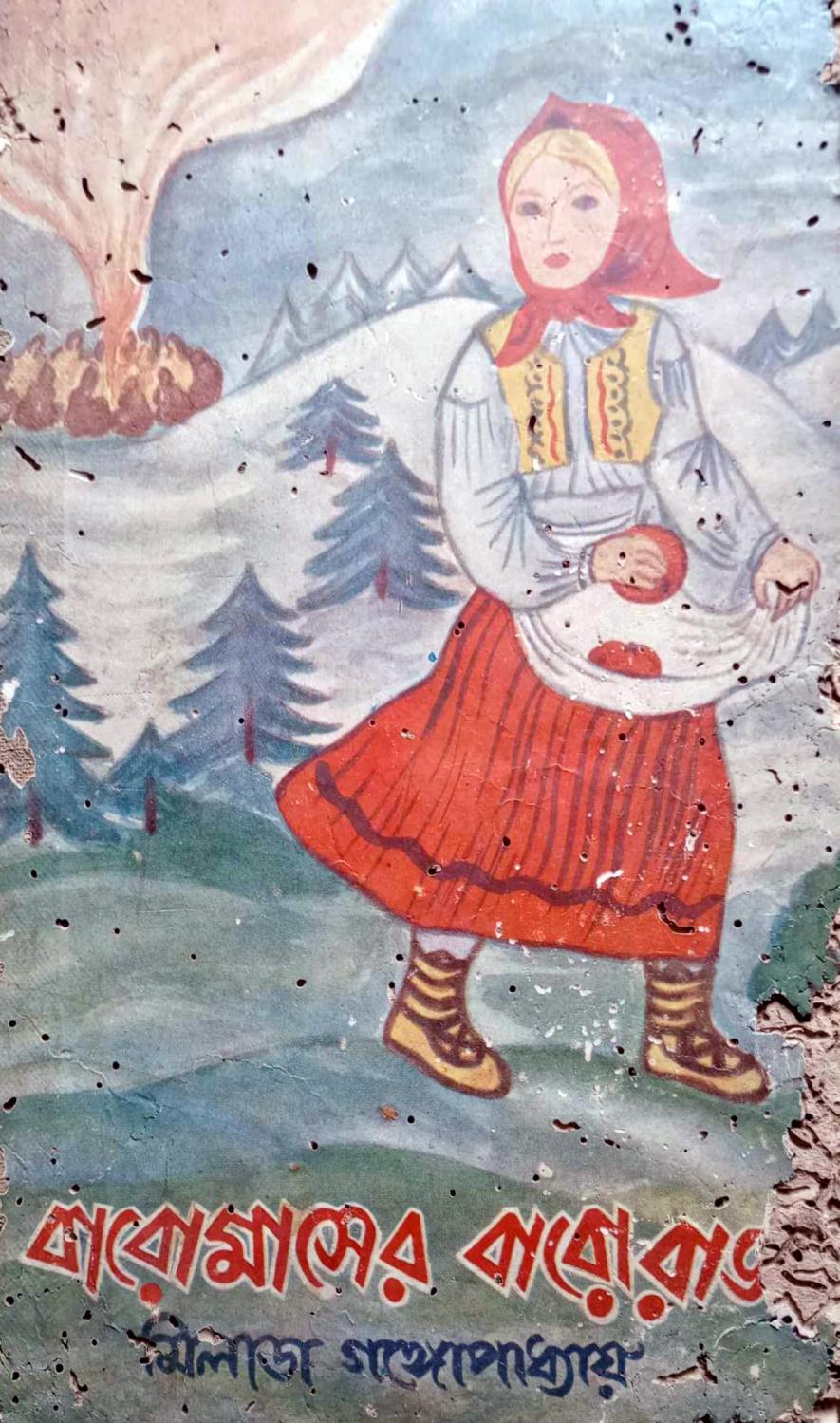

Bengali Book: Cover of বারোমাসের বারোরাজা (Baromasher Baroraja – Twelve Months, Twelve Kings), a collection of Czech fairy tales translated into Bengali by Milada. The cover art is by her as well.

The following spring, Mohanlal took Milada to Santiniketan, where she experienced the legacy of Rabindranath Tagore. It was during the Vasanta Utsava—Santiniketan’s celebration of spring—that she saw, for the first time, Santali tribal girls dancing in a circle.

In her memoirs, she wrote: “The girls, wearing dazzling-white saris with a red border, bright flowers in their shiny black hair, holding one another's hands, formed a circle, in the centre of which two young men were vigorously beating their traditional, long, narrow drums, giving rhythm to the girls' singing. I was so overwhelmed by the graceful movements of the dancers and the accompanying music that I became speechless.”

Milada soon began visiting tribal villages. She was moved by their sense of dignity, self-reliance, and connection to the land. These were not simply research subjects to her; they were living communities preserving ways of life that modernity had not yet erased. Her travels gradually grew more focused. She journeyed through Bengal, Jharkhand, Odisha, and eventually the Northeast.

In 1963, she visited Imphal, capital of Manipur. There, she met Rajkumari Binodini Devi, a princess she had first known at Santiniketan. It was through this encounter that Milada learned about the Nagas, a collection of tribes living in the hills surrounding the valley.

“One day in the marketplace I noticed a group of hillmen... tall, sturdy figures wrapped from neck to foot in gorgeous red and white shawls, bead necklaces drooping on their chests,” she wrote. Intrigued, she asked Binodini Devi who they were. "They are the Nagas," came the reply.

This meeting sparked what became a deep, decades-long engagement with Naga life and culture. At the time, travel to the Naga Hills required a special Inner Line Permit, a colonial-era restriction still in place. With help from friends and officials, Milada secured the permit and joined a convoy of 120 military trucks headed toward the hills. This journey marked the beginning of a profound chapter in her life.

She returned to Nagaland several times over the next 20 years. These visits led to two major books: A Pilgrimage to the Nagas and Naga Art. The former is a sensitive travelogue filled with first-hand observation and personal reflection. The latter offers an in-depth visual and cultural study of Naga architecture, ornamentation, and ritual art. Both books are rare documents that treat tribal cultures not as anthropological curiosities but as dynamic societies with their own aesthetics and philosophies.

Milada’s archive is equally remarkable. The Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) in New Delhi houses her collection of letters, research notes, and original photographs. Among these are her striking black-and-white portraits of Naga women and warriors, village altars, and longhouses. These images are neither exoticized nor posed. They reflect her deep trust with the communities she lived among.

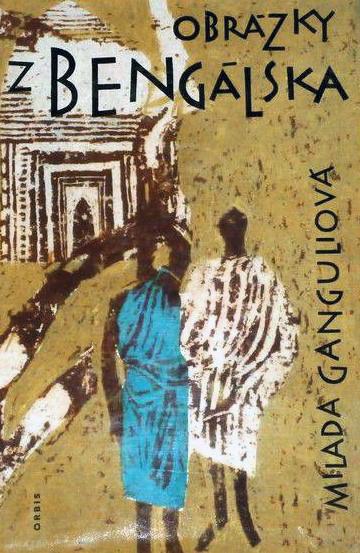

Her legacy, however, is not confined to ethnographic writing. Milada was a prolific translator and cultural mediator. She introduced Czech readers to Bengali culture through her book Obrázky z Bengálska (Images of Bengal). She also translated Czech fairy tales into Bengali—those books are rare nowadays.

Cover of Obrázky z Bengálska (Images of Bengal), authored by Milada.

During the Cold War, when the communist regime in Czechoslovakia kept tabs on its citizens abroad, Milada's name appeared in declassified CIA surveillance documents. A memo noted: “Milada Ganguli’s name was mentioned as one of those who supply information to Czech newspapers.” While these records reflect the paranoia of that era, they also underscore her position as a cultural correspondent, frequently writing for journals like Nový Orient.

Her contributions went largely uncelebrated during her lifetime. But her photographs, books, and translations remain invaluable. They offer insights not just into tribal societies but also into a model of cultural exchange grounded in respect and long-term engagement.

Milada Ganguli was not an academic anthropologist, nor a government ethnographer. She was something rarer: a patient listener and observer who allowed herself to be transformed by what she saw. Her life reminds us that borders can be crossed not just by passports but by empathy, humility, and wonder.

In today’s world—where indigenous communities continue to struggle for recognition and respect—her work stands as both documentation and quiet resistance. Through her lens and language, Milada Ganguli ensured that the voices from India’s hills and forests would not be forgotten.

Pijus Ash is a writer and researcher based in Kolkata, with over two decades of experience in journalism. He is associated with Udbodhan (Ramakrishna Math) and the 'Centre for Indological Studies and Research'. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.