Migrant Workers: Who Will Penalise Errant Law Enforcers?

Image Courtesy: PTI

All through the COVID-19 pandemic, India’s informal and migrant workers have faced extreme adversities. The reason for their suffering is the ineffective implementation of a multitude of existing labour laws. For instance, state governments have not been keeping records of inter-state migrant workmen, despite a law specifically enacted to protect their interests. As a result, the relief meant for migrant workers has still not reached most of them. This is because the basic work of state governments—gathering statistics and data—has never been done.

Governance failures in the three labour laws which concern India’s most marginalised unorganised workers—the Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act, 2008, the Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1996, the related Cess Act passed the same year, and the Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act, 1979—have resulted in tremendous hardship for India’s workers. Now, in December, India is set to notify the four Labour Codes on Wages, Industrial Relations, Occupational Safety and Health and Working Conditions and Social Security. These codes also enhance the penalties for violation or failure to implement the new rules. For example, the penalty for death of an employee has been fixed by the code on occupational safety at up to two years of imprisonment, or a fine of up to ₹5 lakh, or both.

But a basic question arises here: it is the job of the state to prosecute actors in the industrial relations system who fail to comply with laws. In that case, who will penalise the agencies of the state itself—the governments, labour administrations, inspectorates and so on—when they fail to comply? In other words, who will discipline the discipliner? In the Covid-19 context, would should pay for the neglect and indifference of historic proportions that has deprived millions of workers of their promised welfare? A look at each of these three laws and the exact impact of their non-implementation is detailed below:

The Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act

The UWSSA requires the Centre or state government to constitute Social Security Boards with three-year tenures and frame schemes for life, disability, health, maternity, old age pension, injury, and other benefits to workers. These boards and schemes are to be funded jointly or independently by both the Centre and states. Importantly, state governments are supposed to set up facilitation centres for workers, as part of which the district administrations are required to register every unorganised worker on a self-declaration basis. These registered workers are then supposed to be issued smart portable identity cards with unique identification numbers.

However, this important process has been shoddily implemented ever since the act into effect, on 16 May, 2009. At first, on 18 August 2009, the Centre formed the National Social Security Board. Thereafter, the annual reports for 2011-12, 2016-17, 2017-18 and 2018-19 merely state that the board has been constituted. There is no elaboration of its functioning, except the 2015-16 report, which mentions eight meetings of the board took place. None of the annual reports specify any developments regarding registration of unorganised workers.

On 25 December 2015, the government of Gujarat launched a portable benefits card under the Act, named the Unorganised Workers Identification Number (U-WIN), on a pilot basis. It was meant to serve as the model for the entire country to provide benefits to workers under schemes such as Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana, Aam Aadmi Bima Yojana, Atal Pension Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana and Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana.

But in 2016, the Labour Ministry’s proposal for a card for each family of migrant workers (later changed to a card for each migrant worker) was rejected by the Finance Ministry on account of the expenses it would entail. The Information Technology Ministry also turned the proposal down on grounds of duplication with the Aadhaar project. It was reported in April that year that the Ministry of Labour had determined that Aadhaar numbers (combined with existing individual departmental access and validation systems) will be “used to deliver” social security services to unorganised workers. The Labour Ministry projected a budget of ₹6,000 crore for the cards and ₹7,000-14,000 crore for the facilitation centres.

In January 2018, the Labour Ministry, apparently satisfied with the pilot project, announced its intention to register 470 million [47 crore] unorganised workers and providing them with the U-WIN card that would be seeded with Aadhaar. It also considered bringing the workers under the EPFO and ESIC coverage. The Labour Ministry floated a bid for this purpose on 12 June 2018, while admitting the absence of a centralised national database of unorganised workers. It was reported that the ministry therefore accepted the need to build a social security delivery platform that brought various schemes for unorganised workers together.

In other words, U-WIN was supposed to become part of a comprehensive and well-thought-out social security plan of action. Again, in January this year, talk of a digital database to facilitate seamless payments under any scheme to unorganised workers cropped up. Eventually, nothing happened and the workers suffered during the pandemic.

Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act, 1979

Another utterly ignored law, ISMWA, provides an elaborate framework for formalising employment of inter-state migrant workers. It provides for mandatory registration of all principal employers who have five or more inter-state migrants as workers and prohibits employers from hiring such migrants without securing a registration certificate. Licensing officers are supposed to be appointed under this law to investigate the granting, revocation, suspension and amendment of licenses even to contractors who employ five or more inter-state workers. The rules for employment of inter-state workers require both employers and contractors to fill several administrative forms. If they had been complied with, these forms would have provided a rich database of employers, contractors and workers themselves.

Both the National Commission on Rural Labour, 1991, and the National Commission on Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector (NCEUS, 2006-10) flayed the government for “tardy” implementation of the ISMWA. The rate of formalisation of contractors and principal employers via licenses and registrations was found to be “poor”, the prosecution rates were seen as “very weak” and resulting in “persistent vulnerability” of unskilled and poor migrant workers.

Unlike the NCEUS, the National Commission on Rural Labour had made elaborate and specific recommendations for reforms of the ISMWA. For example, it said that a national migration policy must be framed, that the law must be effectively administered, temporary ration cards had to be given to inter-state migrant workers, and many other provisions. But no government paid attention to these. Therefore, despite a central law and an elaborate labour administrative framework involving numerous forms, registers and returns, when COVID-19 struck India, migrants were forced to flee their host states while state governments stared at blank sheets of papers where statistics on migrant workers were supposed to be. This author’s search on the Labour Bureau’s website for even annual reports detailing the workings of the ISMWA proved fruitless.

The Chief Labour Commissioner’s office replied to an RTI seeking statistics on migrant workers filed by an activist on 21 April, with a cryptic bureaucratic response, which also speaks volumes about the implementation of ISMWA: “As per the stat section is concerned, no such details are available based on requisite information,” the Labour Commissioner’s office replied. In early June this year, the chief labour commissioner’s office released some incomplete data. During a hearing on 30 June, the Delhi government itself submitted before the Delhi High Court that not a single worker has been registered under the ISMWA. Further, there was no registration in the Shram Suvidha Portal, the supposed unified portal for filing and registering labour and employment documentation. The High Court observed the “dire need” for a mechanism to register migrant workers in the June hearing. Yet, months after the painful social and economic experiences of millions of workers, the government still has not collected data on workers who migrated, or lost their jobs or died—as the Labour Minister told Parliament during the ongoing Monsoon Session.

Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1996

The government, after considerable pressure from workers’ organisations [specifically the National Campaign Committee on Construction Labour] enacted the BOCW Act and the BOCW Cess Act in 1996. The BOCWA also provides for an elaborate machinery of advisory committees and expert committees, and welfare boards to be set up by states, other than registration and licensing officers, et al. It seeks to ensure comprehensive welfare of registered construction workers, including regulation of their hours of work, overtime pay, good conditions of work, and temporary free accommodation, etc.

In turn, the Cess Act contemplates collection of a 1-2% levy on the cost of construction to “augment” the coffers of the welfare boards. Section 22 of the Cess Act details the causes for which the fund must be used by the boards. These include accidents, pensions, loans for construction of houses, group insurance, financial assistance for children of beneficiaries, medical assistance for major ailments of beneficiaries or their dependents, maternity benefits etc. But the administration of the BOCWA is also a disaster. Workers simply end up not registering because of documentation issues. They are supposed to secure a record of their being employed, while their contractors/employers do not want to formally accept having employed them in order to avoid legal liabilities and “bureaucratic procedures”.

Workers also find it difficult to secure identity cards, Aadhaar cards, and do not want to lose their wages while they spend time getting registered. The foremost reason for lack of registration is that if they do not pay any contribution for two years, they would lose the registration altogether. Construction workers are least likely to be unionised. Hence, they lack institutional assistance. They are also most likely to be inter-state migrants, which makes the already complex procedures even more cumbersome for them.

Since most state governments and Union Territories did not even constitute welfare boards as stipulated in the laws, in 2006, the National Campaign Committee on Construction Labour filed a public interest litigation in the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court directed the central and the state governments to frame and notify rules for the Act, set up the boards and advisory committees, and ensure regular meetings. But still state governments did not spend the money collected under the Act on the welfare of construction workers and instead sought to divert the funds elsewhere, for which the judiciary pulled them up.

In April 2015, the Bombay High Court directed the government of Maharashtra to spend the cess that had been collected for construction worker’s welfare only. Interestingly, it asked the state to consider maintaining a database of construction workers and tackle issues concerning migrant workers.

On 15 March 2018, the Supreme Court lashed out at states in these words: “…this Court has issued a series of directions since May 2008. This Court was compelled to do so since even twelve years after the enactment of the BOCW Act, the basic statutory mandates had not been carried out by the State Governments and Union Territories.” The Court directed agencies to strengthen registration, cess collection, frame a composite welfare scheme, constitute bodies as per the act, issue identity cards, etc. It noted, “There are more than 4.5 crore building and construction workers in the country and earlier about 2.15 crore had been registered and as of now about 2.8 crores have been registered. How these figures have been arrived at is anybody’s guess. In any event, the registration of building and construction workers is well below the required number and is also a guesstimate”.

According to the Standing Committee on Labour, by 31 March 2017, ₹32,633 crore cess was collected, while ₹7,517 crore was spent. But the Comptroller and Auditor General cites different figures: ₹26,137 crore collected and ₹26,009 crore spent. The Supreme Court observed, caustically, “…it is quite shocking that even the CAG does not have all the figures and whatever figures are available, may not be reliable… there is undoubtedly a financial mess in this area and this chaos has been existing since 1996. The only victims of this extremely unfortunate state of affairs and official apathy are construction workers who suffer from multiple vulnerabilities.”

These strictures should have disciplined the labour administration but, sadly, they have not. As figure 1 shows, 24 of the 36 states and UTs (all not shown) had not spent half of the collected cess as on 24 June 2019. Further, only five states had spent more than three-fourths. Surprisingly, Kerala spent more than it had collected.

During the ongoing pandemic, the Ministry of Labour and Employment stated that around 3.5 crore construction workers had registered with state boards, which have about ₹52,000 crore funds collected over the years. The Centre asked states to transfer these funds to the workers to mitigate the crisis.

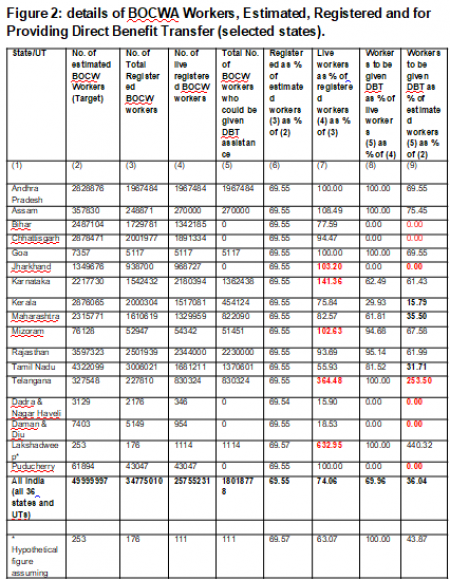

Some of the ratios given in the table below (figure 2) raise doubts over the reliability of data provided by state governments (all not shown). For example, in many states, the proportion of estimated workers registered under the BOCWA shows a remarkably consistent figure of 69.55%. Second, in the case of Jharkhand (103.20%), Karnataka (141.36%), Mizoram (102.63%), Telangana (364.48%) the proportion of workers whose registration was “live” exceeded those earlier registered by whopping percentages. This has serious implications for providing Direct Benefit Transfers.

Are these fantastic figures printing errors or careless mistakes? For Lakshadweep, I have given a different figure in Figure 2, accounting for possible data-entry errors, but in the case of other states, something is surely amiss.

Six states and Union Territories, including Bihar (13.43 lakh workers), Chhattisgarh (18.91 lakh workers), Jharkhand (9.69 lakh workers), Dadra & Nagar Haveli (346), Daman and Diu (954), and Puducherry (43.047 workers) did not disburse a single rupee from the cess to the construction workers, despite directions.

Only a few states and Union Territories, including Andhra Pradesh (69.55%), Assam (75.45%), Goa (69355%), Karnataka (61.43%), Mizoram (67.58%) and Rajasthan (61.99%) provided relief to a good proportion of workers. It is hard to believe that Kerala, which spent more than the funds available (see Figure 1), provided relief only to about 16% of workers with live registration/ Is it because it did not have adequate funds at its disposal? It is shocking that progressive states like Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu fared poorly. At the national level, of the about 49.99 million workers in building and construction sector, only 34.78 million (70%) were registered, only about 75% of the registered workers renewed their registrations, about 70% of registered workers and 18.02 (36%) of the 49.99 million estimated workers were targeted for relief during the pandemic. At any rate, data generated by the states and Union Territories seem suspect.

Conclusion

Once cleared in December, the four labour codes would weaken employment protection even further. Even though the code on industrial relations recognises trade unions, collective bargaining will be difficult as high employment insecurity and dominance of “flexible” category of workers will dominate the scenario. Even the powers of inspectors in the four labour codes do not conform to the provisions of Labour Inspection Convention (081), 1947.

Responding to and even endorsing the “Inspector-Raj” critique, many states have introduced self-certification, third-party auditing and risk-based and randomised inspections, and so on. These reforms ignore the poor implementation record of the inspectorate and its weak personnel and infrastructure. The new codes will surely worsen the historical neglect of workers, making them even less likely to realise the promised bundle of rights and welfare measures.

Various political parties, the labour administration and the inspectorate have failed to deliver what they are legally mandated to. Even the strictures of the Supreme Court have not had effect. Trade unions raised the non-implementation of labour laws in the tripartite Indian Labour Conference and this is part of their struggle agenda. Perhaps the unions should have pitched their demands on these critical issues much more strikingly and persistently. Yet the question is: who will penalise the implementer for governance failures which have brought immense miseries to workers? It is time these issues assume greater importance in the public policy debate. Even a slender labour law framework with minimum rights but with sound implementation appears to be a better choice than grand clauses that promise the world but which remain unimplemented. While recognising this as a rather poor choice in a public policy debate, we do need to ask if the empirical realities force such an extreme trade-off today.

The author teaches human resource management at Xavier School of Management, Jamshedpur. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.