Israel-Palestine Flare-up and the Web of Disinformation in India

Representational Image.

Fake news about dead babies is used for rabble rousing so that the planned murder of real babies gains acceptance, writes Prachi Arya.

—

The news of the alleged beheading of Jewish babies and children by the fighters of Gaza administrator Hamas in the latest flare-up between Israel and Palestine spread like wildfire and has had a worldwide impact.

However, more recent expositions have sought to establish the falsity of videos of Hamas beheading Israeli babies and using people, including children, as shields.

In another instance, a viral video from 2016, of a Syrian rebel group beheading a boy in Aleppo, was posted on Twitter and linked to the current crisis. Upon fact-checking, similar other visuals from 2016, unrelated to the current flare-up, were also found to be falsely linked to the recent violence.

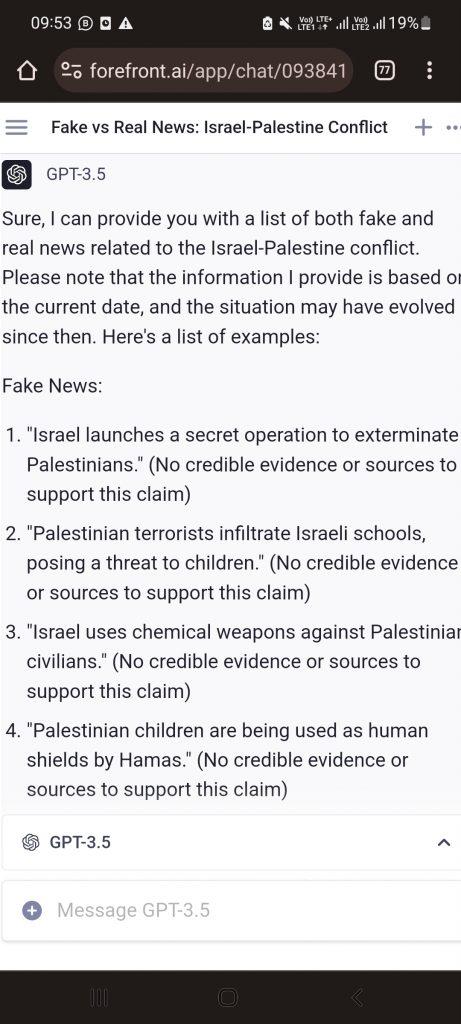

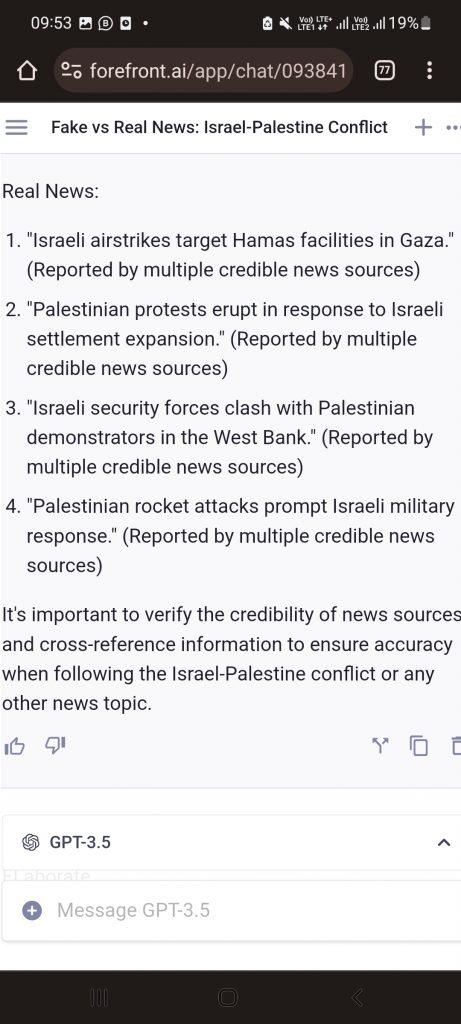

A quick search on the artificial intelligence supported platform Chat GPT indicates that reports of minors being targeted by Hamas are unverified and probably false.

A recent Al Jazeera article underlines the fact that most anti-Palestine disinformation originated from India. It also highlights the rise of online disinformation spread by far-right accounts in India.

An Al Jazeera mentions that accounts allegedly linked to the ‘BJP IT cell’ have been actively spreading disinformation related to the latest Israel–Palestine flare-up.

The article mentions that accounts allegedly linked to the infamous Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) ‘IT cell’ have been actively spreading disinformation on the Israel–Palestine conflict.

‘BJP IT cell’ is a broad-based term used to describe the social media and online communication wing of the Hindu right-wing party which is currently the ruling regime in India. The party’s IT cell plays a significant role in shaping its online presence, disseminating information, and engaging with supporters and critics alike.

The Indian disinformation campaign includes false claims of Hamas kidnapping a Jewish baby and a video falsely depicting Palestinians kidnapping people to be made sex slaves.

The Al Jazeera article finds that many of the accounts sharing these false videos also engaged in posting anti-Muslim comments on social media platforms. Such narratives only serve to flame hatred and disseminate Islamophobia and hate speech online.

Fake news for more views

When global crises and emergencies occur, whether it is the Covid pandemic or warring countries, technology is often co-opted to serve the narrative of powerful stakeholders.

In such situations, online sources that usually connect people around the world and provide access to critical information become a tool to manipulate public sentiment.

Accusations of people, including children, being used as shields in both Israel and Palestine are not new. In fact, the long-drawn conflict between Israel and Palestine has been marred by accusations and counter-accusations regarding the use of human shields, particularly involving children. Both sides have made such claims against each other, including in 2018 and 2007.

Israeli forces deliberately place civilians, including children, in harm’s way to deter attacks or to gain a tactical advantage, as observed by Amnesty International and the United Nations, who have documented cases where Palestinians were allegedly coerced or forced to act as human shields. On the other hand, Israel has accused Hamas of deliberately using Israelis and Palestinians, including children, as human shields.

The highly polarised nature of the conflict often leads to conflicting narratives and interpretations of events. Further, investigations into these allegations are often hindered by limited access to conflict zones and the lack of cooperation from both sides.

The highly polarised nature of the conflict often leads to conflicting narratives and interpretations of events. Further, investigations into these allegations are often hindered by limited access to conflict zones and lack of cooperation from both sides.

It is important to note that while the pervasive use of digital technologies exacerbates disinformation, it is by no means a product of information technology. False news predates the rise of the internet and the widespread use of digital platforms for news.

For instance, the news of Hamas harming babies is strikingly similar to the Gulf War reportage claiming that Iraqi soldiers had removed babies from incubators in Kuwait hospitals and left them to die. This story was widely reported and influenced public opinion, but it was later revealed to be a fabrication— part of a well-orchestrated propaganda campaign aimed at justifying military intervention.

What is the impact of false information?

In the digital age, the menace of false information is pervasive and has become a pressing concern. False information, referred to as disinformation when intentional and misinformation when unintentional, has far-reaching consequences. It does not just shape public opinion and influence events such as elections but may also incite violence.

The 2018 ‘WhatsApp Lynchings’, where messages circulated on the popular messaging platform WhatsApp spread canards about child kidnappers operating in various parts of the country and led to a wave of panic and fear among the public, perfectly illustrate this phenonemon. Tragically, multiple people lost their lives as a result of mob attacks following the false rumours.

Such disinformation can include doctored images, videos and text messages, which may be designed to manipulate emotions and provoke a sense of urgency that leads to the rapid spread of false information.

Arguably, the perniciousness of fake news reached its zenith during the Covid pandemic, leading to an ‘infodemic’ due to the abundance of misinformation.

In the WhatsApp lynching case, the lack of verification and critical thinking, combined with the rapid spread of these messages, led to a dangerous situation where innocent lives were lost due to the dissemination of false information.

Arguably, the perniciousness of fake news reached its zenith during the Covid pandemic, leading to an ‘infodemic’ due to the abundance of misinformation. Among other things, this included false claims about unproven treatments or cures, as well as dangerous misleading information on self-medication.

Even when lives are not at stake, the psychological impact of fake news can cause profound damage. Fake news often employs emotional manipulation techniques, such as using compelling narratives or evocative imagery, to elicit strong emotional responses.

When individuals come across alarming or distressing headlines, it can trigger emotional responses such as fear, anger or anxiety, contributing to heightened stress levels that negatively impact mental health.

As individuals struggle to discern what is true and what is false, the constant exposure to misinformation can lead to a state of heightened vigilance and mistrust, contributing to a general sense of unease and anxiety in an already tense situation.

What are Indian laws regarding fake news?

In India, fake news is regulated through a complex legal framework that covers cable TV, newspapers, online platforms and films that are used to handle cases such as the 2018 WhatsApp lynching incident.

To illustrate, the Supreme Court of India, in the case of Tehseen S. Poonawalla versus Union of India prescribed certain guidelines to state governments, including the registration of a first information report (FIR) “under Section 153A of the IPC and/or other relevant provisions of law, against persons who disseminate irresponsible and explosive messages and videos having content which is likely to incite mob violence and lynching of any kind.”

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) contains provisions that can be applied to cases involving fake news and misinformation. Sections such as 153 (provocation with intent to cause riot), 153A (promoting enmity between different groups on the grounds of religion, race, etc.), and 505 (statements conducing to public mischief) can be invoked to address instances where fake news leads to violence, communal disharmony or public disorder.

The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 provides the legal framework for investigating and prosecuting criminal offences in India. It includes provisions that can be applied to cases involving fake news, such as the power to conduct searches, seize evidence and arrest individuals involved in disseminating false information.

When individuals come across alarming or distressing headlines, it can trigger emotional responses such as fear, anger or anxiety, which contribute to heightened stress levels that negatively impacts mental health.

More recently, Section 195(d) of the proposed Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Bill, 2023, which was introduced in Lok Sabha in August to revamp Indian criminal laws, seeks to punish the spreading of fake news or misleading information that jeopardises the sovereignty and security of India with jail time of up to three years or a fine, or both.

The Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act) includes provisions to address various cybercrimes. The dissemination of disinformation and misinformation is primarily dealt with under Section 79 of the IT Act.

The Section provides immunity to intermediaries, such as social media platforms, from liability for any third-party content hosted on their platforms. However, intermediaries are also required to comply with certain due diligence requirements, including taking down or restricting access to unlawful content upon receiving a court order or a government directive.

Thus, while the Section offers protection to intermediaries, it does not absolve them of their responsibility to address fake news. If an intermediary receives actual knowledge or is notified by the appropriate government agency about the presence of fake news on their platform, they are required to promptly remove or disable access to such content.

In recent years, the need for intermediary liability and regulations to address the spread of fake news has been highlighted. The Indian government aimed to hold intermediaries accountable for the dissemination of false information and proposed amendments to the IT Act to address this issue more effectively.

These developments culminated in the notification of the Information Technology (Intermediaries Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (Rules) in February 2021. Although they do not directly address fake news, the Rules require online intermediaries and news publications to comply with certain baseline measures for addressing the issue of fake news and misinformation.

However, due to the alleged draconian nature of the Rules, they are facing several legal challenges in Indian courts.

One problem is that the attempts by the government to regulate fake news, as exemplified by the amendment to the IT regulatory framework, have a tendency to make the government the sole arbiter of what is true and what is false. This is obviously problematic, particularly in democracies, because governments are run by political parties which have a vested interest to present one version of ‘the truth’ at the cost of others.

The Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act), includes provisions to address various cybercrimes. The dissemination of disinformation and misinformation is primarily dealt with under Section 79 of the IT Act.

While the Indian government’s efforts to tackle fake news are commendable, several challenges persist. The sheer volume and speed at which misinformation spreads on social media platforms pose a significant challenge. The lack of awareness and media literacy among certain sections of society also hampers the effectiveness of these initiatives.

Importantly, striking a balance between curbing fake news and protecting freedom of speech is a delicate task as government overreach may cause a chilling effect on free speech and much-needed critical journalism.

What is the response of social media and online platforms?

The response of social media platforms to disinformation has been mixed at best. It involves measures such as implementing fact-checking systems to identify and label false or misleading information as well as to provide users with additional context while directing them to verified sources of information.

Apart from partnering with fact-checkers, online platforms also undertake content moderation and removal, as well as algorithmic adjustments to reduce the visibility of false or misleading content and promote reliable sources of information from trusted sources. User reporting and flagging also help platforms identify and review potentially problematic content more efficiently.

For instance, Google’s approach to fighting misinformation online involves teams of experts working to provide users with high-quality and trusted information, while also reducing the spread of harmful content. The company has implemented rules and policies across their services to prohibit certain types of misinformation.

Google also collaborates with partners worldwide to counteract fake news and has signed agreements such as the European Union (EU) Code of Practice on Disinformation. The tech giant has also explored innovative approaches such as prebunking to build resilience against misleading narratives.

While Google and other online platforms have been collectively called out by lawmakers from the EU and United States (US), X (formerly Twitter) seems to have emerged as the biggest loser in the war against disinformation.

While Google and other online platforms have been collectively called out by lawmakers from the EU and the US, X seems to have emerged as the biggest loser in the war against disinformation.

X has faced more controversy regarding its approach to fake news since Elon Musk took over the social media company. According to their website, X aims to create a safe and informed environment by taking various actions against misleading content.

They have separate policies for crisis misinformation, synthetic and manipulated media, and election integrity. Misleading content confirmed to be false or shared in a deceptive manner may be labelled, have reduced visibility, or be removed. X also takes actions to inform and contextualise by sharing information from third-party sources.

They may prompt users when engaging with misleading posts and launch pre-bunks during important events. X is also testing features for users to report misinformation and provide additional context through ‘community notes’.

However, there has been a flood of disinformation and fake news on the platform, mainly related to the latest Israel–Palestine flare-up since the platform made changes that removed headlines while displaying articles and due to heavy layoffs in its ‘trust’ and ‘safety’ teams that oversee daily communications and mitigate the posting and spread of false content. These changes have raised concerns about X’s ability to provide reliable information.

The problem of disinformation through videos is not limited to pro-Israel propaganda. Last week, a viral video on X supposedly showed a Hamas fighter firing a shoulder-mounted rocket cannon and taking down an Israeli helicopter. Later, the footage was found to be from a video game called Arma 3. However, despite community notes pointing out its deceptive nature, the video is still up on multiple accounts on X, and even Facebook.

Who watches disinformation from the watchdogs?

BJP IT cell is known for its extensive use of social media platforms, including X, Facebook and WhatsApp, to promote the party’s agenda, counter opposition narratives, and mobilise support. Listed as the ‘IT, website and social media management’ department on the BJP website, it is often described as a well-organised strategic unit.

Members of the BJP IT cell are known for their active participation in online discussions, debates and campaigns. They often amplify the party’s messages, defend its leaders and policies, and disparage political opponents.

The problem of disinformation through videos is not limited to pro-Israel propaganda. Last week, a viral video on X supposedly showed a Hamas- armed fighter firing a shoulder-mounted rocket cannon and taking down an Israeli helicopter. Later, the footage was found to be from a video game called Arma 3.

The IT Cell is also involved in monitoring and responding to news articles, fact-checking the opposition party’s claims, and disseminating party-related information.

Increasingly, it is evident that some sections of the BJP, especially the BJP IT cell, have been involved in spreading misinformation, fake news and hate speech, although not all members of the BJP engage in such activities. For instance, a recent report found that 205 or 80 percent of the 255 documented anti-Muslim hate speech from gatherings in the first half of 2023 occurred in BJP-ruled states and Union territories.

This complicates an already divisive scenario, where sections of the political party in power may be actively involved in spreading disinformation about the ongoing Israel–Palestine flare-up.

What are some solutions to combat fake news in situations of crisis?

The availability of real solutions seems to be at its nadir, considering the magnitude of disinformation and its deleterious effects. Moreover, it is increasingly evident that politicians and powerful technology companies may ultimately profit from fake news.

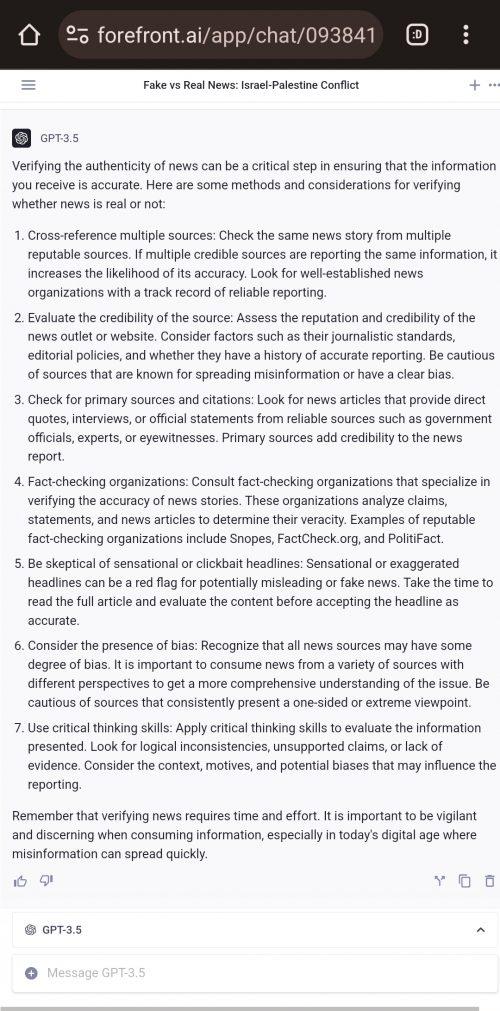

Various platforms such as news agencies and ChatGPT suggest that users take matters into their own hands and verify the authenticity of news.

Establishing fact-checking organisations specialising in verifying the accuracy of news stories. These include Snopes, FactCheck.org, and PolitiFact. Indian fact-checkers include boomlive.in and altnews.in. This should be a growing tribe.

Some suggested measures include:

-

Cross-referencing multiple sources and using well-established news organisations with a track-record of reliable reporting.

- Evaluating the credibility of sources considering factors such as journalistic standards, editorial policies and history of accurate reporting while being cautious of sources known for spreading misinformation or having a clear bias. 3. Checking news articles for primary sources and citations that add credibility to news reports.

- Establishing fact-checking organisations specialising in verifying the accuracy of news stories. These include Snopes, FactCheck.org, and PolitiFact. Indian fact-checkers include boomlive.in and altnews.in. This should be a growing tribe.

- Being sceptical of sensational or clickbait headlines and reading articles fully and substantially to evaluate the content before accepting the headline as accurate.

- Considering the presence of bias and being cautious of sources that consistently present a one-sided or extreme viewpoint.

- Using critical thinking skills and looking for logical inconsistencies, unsupported claims or lack of evidence.

Another solution lies with relatively neutral truth-finding bodies such as the UN. Through the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, it included East Jerusalem Palestinians and Israelis undertaking an extensive investigation of “current events and identifying those responsible for violations of international law on all sides, both those directly committing international crimes and those in positions of command responsibility.”

Undeniably, even if facts triumph over disinformation in this battle for truth, the Israel–Palestine crisis only seems to be worsening. Much like the fake news of beheaded babies, real children on both sides are its most tragic victims.

Prachi Arya is a law and policy consultant, having worked with the tech industry for a decade

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.