Is the Military Brass Transgressing the Diplomatic LAC?

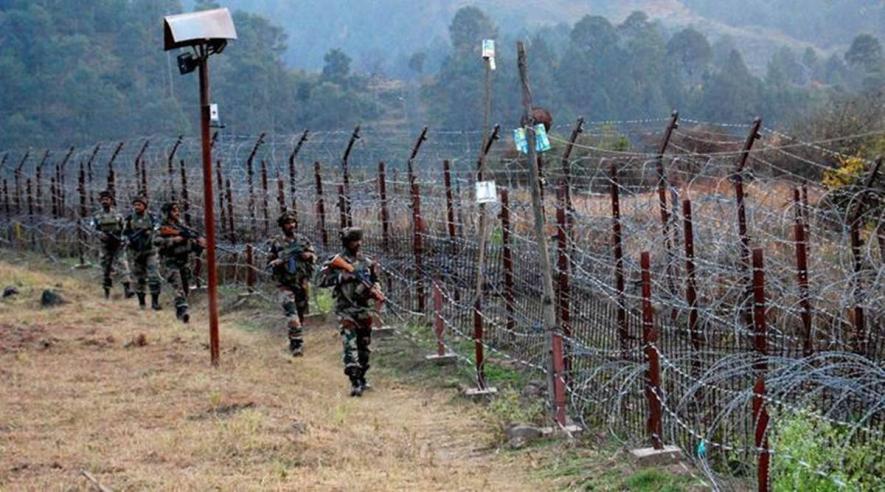

Image Courtesy: The Indian Express

On 27 October, the chief of the Western Command of the Air Force expressed the hope that the Pakistan-occupied part of the erstwhile princely state of Jammu and Kashmir would someday be part of India. He said so at a function at the Budgam airfield to re-enact the landings on the same date in 1947 to save Kashmir from the Kabali raids.

Then, while delivering the first Ravi Kant Singh Memorial lecture, Chief of Defence Staff General Bipin Rawat referred to Chinese inroads in India’s neighbourhood. He said, “Such attempts and adventures in the neighbouring countries would go against India’s national interest and are potential threats to India’s territorial integrity and strategic importance.” Further, almost as if India is not already at it, he noted, “We have to…assure our neighbours that we are their permanent friends and want to engage with them on equal terms,” and that “we need to be able to convince them that we will be your [their] friends in the long term.”

Late last month, the Vice Chief of the Army Staff, speaking at a seminar, said, “...if Tibet had strong armed forces, they would have never been invaded.” It is apparent he was underlining the necessity for a nation to have strong armed forces. Not naming a country referred to as the big nation, he said, “...today, everybody talks about India as the net security provider and it is a security umbrella against a big nation.”

From the three illustrations above, it is clear that this plain-speak by the brass, on wider than narrowly military aspects of national security, is a trend. In other words, in officialese, it is not an aberration. These statements, in quick succession of each other, point to a policy decision to have the brass give voice to matters beyond the pale of the narrowly military.

It is not as if the foreign office has not gently pushed back. In September, the infamous clash of civilisations thesis acquired a new subscriber in the CDS, just before the foreign ministers of India and China met on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation gathering. Then, no less than Foreign Minister S Jaishankar stepped in to contain the fallout by distancing India from the general’s words.

However, there has been little public skirmishing on the continuing inroads the brass seems to be making into diplomatic turf. Can we infer that select members of the brass have been empowered to participate in, if not lead, in national security-relevant messaging?

Perhaps the coordination on this score rests with the National Security Council Secretariat (NSCS), so that the two branches of government and instruments of national security—military and diplomacy—do not step on each others’ toes and elbow each other in areas of inevitable overlap.

With theaterisation growing and plurilateralism being the foreign policy mantra, it is seemingly unexceptionable that the military is visibly getting into higher gear and batting at a higher than operational level. Military exercises and exchange visits now occur at a pace that is difficult to follow. The fledgling Department of Military Affairs (DMA) appears to have heightened the salience of the military within government and increased the scope of activity of the military outside the traditional domain of guarding the borders and counter-insurgency.

Regarding statements directed at China, the brass taking on an additional duty of strategic messaging gives the foreign office sufficient space to pursue a negotiated end to the continuing crisis. Besides, India perhaps wants to outgun the Peoples’ Liberation Army in its information war salvos, launched in media battles that have followed the fraying of relations between the two states.

As for Pakistan, even as the military presents an implacable front, the national security bureaucracy can continue its below-the-radar engagement, such as the Line of Control ceasefire and the recent invitation to the Pakistan national security adviser to discussions on Afghanistan in Delhi. In any case, Pakistan is fair game since a hybrid war is ongoing, of which the information war is a crucial domain.

This is a positive interpretation of the new practice. However, the military has certainly gone beyond military diplomacy.

None of the eight bullet points on the ambit of the CDS and the DMA, as given in the Second Schedule to Government of India (Allocation of Business) Rules 1961, have anything to do with diplomacy. At best, it is the Department of Defence under the defence secretary that has a role beyond matters that are not strictly military, if the last bullet point in its charter (Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, National Defence College and any other organisation within the Ministry of Defence whose remit is broader than military matters) is an indicator.

Therefore, the newfound practice begs the question, whence did it originate. There are three possible impulses.

The first is understandable, but only at a stretch. Given the recurrence of military forays into diplomatic terrain, the military may have been allowed greater leeway, with diplomats acquiescent. It strengthens India’s strategic profile and outreach, particularly since the Foreign Service has for long been criticised for having too small a cadre to be able to punch at India’s weight.

The second—uncharitable—one is that these interventions stem from an autonomous expanded interpretation of national security after the creation of the DMA. The Chief of Defence Staff has acquired a reputation for speaking his mind on national security. His alleged proximity with the National Security Adviser Ajit Doval perhaps emboldened him. Taking a cue, his fellow generals are now more voluble, even in matters other than diplomacy.

The third—seemingly implausible but not impossible to visualise in an India whose institutions stand reduced to rumps—is that national security minders have sparked off an incipient turf war. The resulting bureaucratic politics places them in the position of arbitrating. Could friction between Doval and Jaishankar have escalated to the level of national security bureaucrats using the military to intrude onto the diplomatic turf?

While the latter two impulses are obviously undesirable, even the first—a reasoned policy to use the military for sniping at neighbours—is not without its underside.

The underside can be seen through reasoning why China inexplicably intruded into Ladakh early last year. A possible reason could be the disconnect between what China heard at the informal summits at Wuhan and Meenakshipuram and what it was experiencing on the ground along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The then eastern army commander had said that the army had transgressed the LAC twice as many times as China, while General VK Singh cited a five-fold higher figure than China. When the military operating within its domain (patrolling the LAC) leads to blowback, blowback is virtually inevitable when it works outside its realm.

While military diplomacy does reinforce diplomatic firepower, the military brass shooting its mouth off is not quite military diplomacy. Even if it is policy to allow the brass latitude, and has diplomats on board, the newfound practice calls for a review. If impelled by the latter two impulses—military expansionism or bureaucratic politics—the need is even greater.

The author is a former infantryman and writer. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.