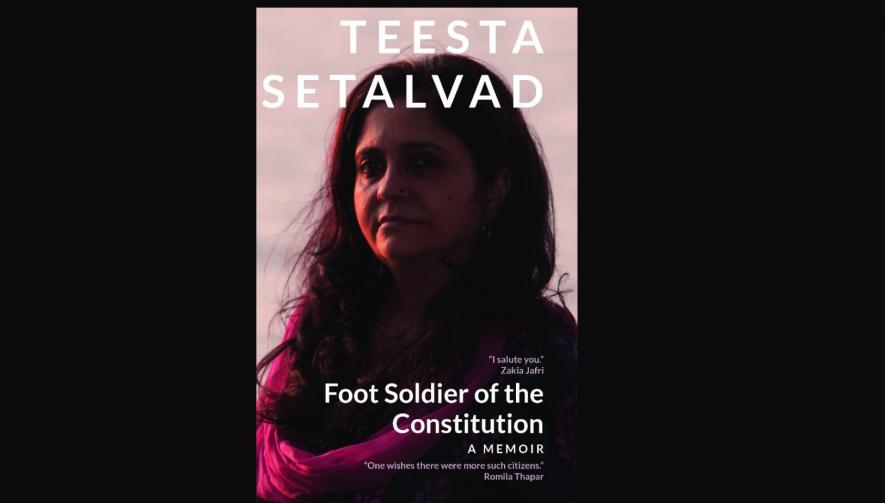

An Interview with Teesta Setalvad and an Extract from her Memoir Foot Soldier of the Constitution

Foot Soldiers of the Constitution

"On 28 February 2002, the parliamentarian Ahsan Jafri was brutally killed by mobs during the Gulberg Society incident in Ahmedabad city. Four years later, on 8 June 2006, his wife – Zakia Ahsan Jafri – sent a complaint to the Gujarat DGP, P. C. Pande, asking that a First Information Report (FIR) be registered on his murder. The complaint was made out against Chief Minister Narendra Modi – as accused number one – and sixty-two others, including cabinet ministers and Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and IPS officials, under section 154 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC). The 119-page complaint was backed with over 2,000 pages of annexures as evidence."

– Teesta Setalvad, Foot Soldier of the Constitution

Indian Cultural Forum interviews Teesta Setalvad on her recently released memoir Foot Soldier of the Constitution. As a journalist she has documented the three communal riots that shaped India – 1984 Bhiwandi riots, 1992-93 Ayodhya Riots and 2002 Godhra riots. While she has been writing about other people, here, she shares her experience of writing about herself and her life in her memoir.

Following is an extract from Teesta Setalvad's memoir released in January 2017. These extracts are from the chapter titled 'Let Hindus Give Vent' (pages 94-6; 107-9).

I reached Gujarat in early March 2002. I began to scour the relief camps and districts, then, returned back to Ahmedabad, exhausted. Late in the early morning hours, I would pen the alerts for the statutory bodies, the Supreme Court, the President of India, NHRC and other human rights forums. The overwhelming sense when I described things back home to Mumbai was – ‘If Bombay ten years ago was bad, then Gujarat is one thousand times worse.’ In the first six months, I was physically attacked five times. Twice the drivers of hired vehicles abandoned me in villages, fearful of the consequences of the journeys for them. Within days of the coverage, a resolve shaped into a dogged commitment based on these dual experiences: of having lived through Bombay 1992-1993 and now Gujarat 2002: mere documentation and advocacy and campaigning on the targeted mass crimes that exposed bitter fault-lines of bias and prejudice in our institutions of democracy and governance, would not be enough. It was time to test the criminal justice system, from several angles; can justice ever be done when mass violence happens? Can our courts restore the faith in the system? People’s confidence and trust in their neighbourhoods, and even their friends, had been snatched away.

This is what I told Javed in the nightly calls I made. Since I was away alone till odd hours, there was incessant worry at home. I remember saying that now we need to move the courts and see if justice can be done, to test the system and ask whether there can be recompense. We knew that this task could not have been undertaken by us alone and that we would need a strong body of citizens committed to the rule of law to take on that task. That was how Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP) was born. In early April, in Nandan Muluste’s home, Pankaj Shankar showed us the uncut version of In the Name of Faith. It was a raw film that depicted all that needed to be said about the gross cruelty that was deliberately allowed free reign. Those of us in the room – Alyque Padamsee, Cyrus Guzder, Kadrisaab, Nandan Maluste, Shireesh Patel, Anil Dharker, Ghulam Peshimam, and Javed Anand – watched the film. Taizoon Khokharkiwala and his wife Edith have also been fellow travellers in our intense journey. Tears flowed freely at that screening. They turned to disbelief and anger at the extent of abdication of constitutional governance. We then resolved to action. It is no coincidence that those who were present that day were also among those who had been at the forefront of the citizen’s mobilizations after the Babri demolition and Bombay pogrom in 1992-93. The understanding and connections between the two bouts of violence, both of which reflected state complicity at different levels, were there.

If our Courts, politicians, bureaucrats and policemen, had punished the perpetrators of 1984, then the violence of 1992 would not have so easily happened. If the survivors of the Bombay killings of 1992-1993 had earned real reparations and justice, none in the political class, bureaucracy and police, would have so easily beaten the 2002 drum. It is this all-pervasive culture of impunity that has allowed the perpetrators of mass violence, partition and post partition, to go scot-free. Within India’s administration and police force, too – barring a few, stray and rare exceptions – the steel frame resists accountability and transparency. It closes in like an armour of protection, freezing out and targeting even those who pursue the path of justice. 1

Filmmaker Pankaj Shankar was to re-surface in the narrative later (2004-05), when Zahira Shaikh turned hostile for a second time in Mumbai in 2004. Among the footage he had shot in those early days in 2002 were scenes of the BEST bakery carnage the day after the incident (2 March). There was footage with Zahira recording in detail, what was her initial reaction to the carnage – what the law considers a first information report (FIR) about the crime. When Zahira tried, after November 2004, to deny that she had ever done this, the footage told its own tale. Shankar not only allowed himself to be grilled by a crude defence led by Shiv Sena’s former member of parliament – Adhik Shirodkar – but refused to crack under the venomous onslaught. The judgment of the trial court has a significant section on the validity of this video testimony. It indicts the Shiv Sena counsel – Shirodkar – who spent a significant amount of the court’s time during the pre-trial phase abusing my family name and me. For people like Shirodkar, it was the name ‘Setalvad’ that had pulled Thackeray to court in 1993. It had again proved to be a thorn in the flesh of the post-2002 crude and violent Hindutva project. 2

CJP aimed to try and take up legally every aspect of the genocidal carnage, be it cases for relief camps or compensation, missing persons, accountability or the actual criminal trials. In all, we have so far fought as many as 68 cases right from the trial court up to the Supreme Court. As many as 150 convictions have been achieved (of which one hundred and thirty-seven resulted in life imprisonment at the special sessions court stage. In October 2016, the Gujarat High Court acquitted 14 of those earlier convictions in the Sardarpura case, bringing the total number of those convicted to life imprisonment to 123). The NHRC recommended that eight of the critical trails should be independently investigated.

The Superior Courts, both High Courts and the Supreme Court, are vested with the powers of original jurisdiction. Courts have exercised their inherent powers with regard to the enforcement of fundamental rights. In addition, there exists a unique power held by the courts – the suo motu jurisdiction. This enables the Court to intervene soon after they are cognisant of or made aware of some wrong that needs judicial intervention and correction.

This is a powerful phrase in legal parlance that can be used by the Courts to inspire faith and confidence. These are Latin phrases. Suo motu means ‘on its own motion’. It is equivalent to the term sua sponte – when a lofty institution of the government acts on its own cognisance when there is a gross violation of fundamental rights. The term habeas corpus is another significant term. It refers to a writ action demanding that a person be produced in the court – literally. The phrase says – You May Have the Body.

Under suo motu, the Courts have taken up matters and issues on their own, when they receive a letter of complaint and when they read a media report. The power of the suo motu has been used once by the Supreme Court to query the defacement of the mighty Himalayas, letters to the Court have been converted into PILs by high courts and the Supreme Court. When mass crimes against sections of our own population shook the core of the Indian republic, the power of suo motu has not been used. I have in mind the widely-reported 1983 Nelli massacre, the extensively covered (after the first few days of paralysis and silence) 1984 Delhi riots, the 1989 Hashimpura-Meerut killings (when the bodies of those shot dead were washed upon the shores of the Yamuna, near Delhi), the 1992-93 Bombay riots and the 2002 Gujarat pogrom. Nor has the power of suo motu been used in the case of heinous caste crimes. A poignant question regarding the rarely exercised power of the suo moto intervention was put to me by Rajah Vemula – the brother of Rohith Vemula, the Dalit student whose death on 17 January 2016 has been seen as a rejection of institutional callousness and bias embodied by the Modi regime. Rohith Vemula’s family and fellow students filed a case in the Hyderabad High Court against the Vice Chancellor Appa Rao Podile. It languishes in the courts. Despairingly, Rajah Vemula asked me, ‘Can’t the Court intervene with the power of suo motu?’ Ashamed, and forced to answer on behalf of a system that has given us limited redress, I could not reply.

The Gujarat High Court did not – on a suo motu basis – take up any matter related to the 2002 violence. Never mind that two judges, one retired and one sitting of that very high court, were physically attacked. The Chief Justice of the Court is on record stating that they needed to protect themselves by moving to Muslim majority areas, as he had no faith in the law and order machinery. The letter of Justice A. N. Divecha, one of the two judges who were attacked, is a public document annexed to the report of the NHRC of 2002. The other judge was Justice M. H. Kadri. It remains a shameful reminder of the depths to where we had fallen in 2002. The Investigation records in the Zakia Jafri case show that the first attack on a Judge was within a short distance of the Gujarat High Court. It took place on the morning of 28 February 2002. No adequate protection was given to either of the judges, sitting and retired. Both, as it turned out, were Muslims. 3 This remains a serious question mark and blot on the government and administration.

Notes:

1. In the issue of Communalism Combat to commemorate the fifth anniversaryof the Gujarat genocide (July-August 2007), I recounted how many of the powerful bureaucrats – complicit in constitutional actions under NarendraModi – had been carefully and quietly rehabilitated in key ministries of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA I) government. Those policemen who continue to be targeted, such as Rahul Sharma and R. B. Sreekumar, are those who refused to compromise on their stance vis-á-vis 2002. They are still being made to pay for raising the bar, testing the system, with difficult and uncomfortable questions.

2. Later amidst much fanfare and drama, Shirodkar’s counsel got some of these remarks expunged when the appeal in the Best Bakery case was heard in Mumbai.

3. Justice Kadri died in 2014. Justice Divecha died in 2016.

Read the Concerned Citizens Tribunal's report, Crimes against Humanity: An Inquiry Into the Carnage of Gujarat here.

Also read our interviews with Teesta Setalvad here and here.

Teesta Setalvad is a civil rights acitivist fighting for justice for the victims of Gujarat riots 2002. She is also the co-editor of Communalism Combat.

Published here with the permission of LeftWord Books.

© LeftWord Books, 2017

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.