Indian Muslims After Ayodhya: Way Ahead and Challenges

Image Courtesy: Outlook India

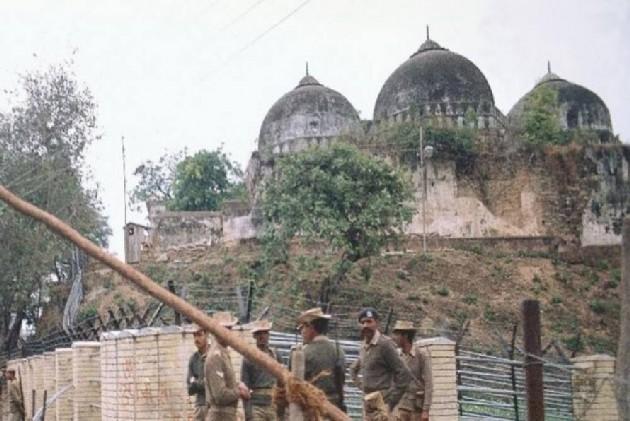

As a section of media and the populace rejoice over the foundation ceremony of a “grand temple” in Ayodhya, where the historic Babri mosque had stood for almost 500 years until extremist Hindus brought it down in broad daylight on 6 December 1992, Muslims are perplexed over how to respond. There was no mosque for the past 28 years at the disputed site, and a fully-functioning Hindu temple had been set up after the demolition, but the way the government machinery cleared the way for the construction of a temple has completely shocked them.

For the 200 million-strong Indian Muslim community, Prime Minister Narendra Modi laying the foundation stone in the presence of Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath and RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat was a terrible sight. To their mind, the Supreme Court, despite incriminating evidence, handed over the land that belonged to the mosque and Muslim petitioners to a trust, a majority of whose members come from those who backed the demolition of the mosque, the VHP and RSS .

Ozma Siddiqui, a Jeddah-based scholar, says that now is among the toughest times the Indian Muslims have seen. The demolition of the Babri mosque was the “last significant episode” of communalism directed against Indian Muslims. That event was heavily censored by the state-run television in India, but international media ran it “live across the world, exposing the assault on the secular fabric of India.” She says that that episode laid bare the damage an exclusive political ideology can do. “Now, those who opposed the existence of the mosque have won, and there are celebrations in RSS pockets in countries such as the United States, where big banners announced the stone-laying ceremony for the temple at the Ayodhya site,” she says.

And yet—though some may find it amazing—at this moment, the mosque is not as high on the agenda for Muslims. Many feel that their community has done precious little to safeguard the rights that the Indian Constitution has guaranteed them. They feel that if they have equal rights as any citizen of the country then they must engage with the field of civil liberties and work to ensure that those rights are not taken away or ignored. They are also concerned about things that have kept them on a trajectory of backwardness: lack of education, employment and entrepreneurship are of immediate concern.

Muslims are aware of their most precarious situation in terms of educational and economic attainments. Their share in jobs and education has steadily dwindled over the decades. Christophe Jaffrelot and Kalaiyarasan A say in a recent report, “Only 39 per cent of the community in the age group of 15-24 are in educational institutions as against 44 per cent for SCs, 51 per cent for Hindu OBCs and 59 per cent for Hindu upper castes.” The same report says that a sizeable proportion of Muslim youth are quitting formal education and moving into the NEET category. “Thirty-one per cent of youth from the community fall in this category—the highest from any community in the country—followed by 26 per cent among the SCs, 23 per cent among the Hindu OBCs, and 17 per cent among the Hindu upper castes. This trend is more pronounced in the Hindi belt,” the authors say.

It is not that Muslims have not improved over the years in their enrolment in primary education or higher education. On the contrary, they have made progress, particularly in higher education. However, in absolute terms, they are way behind other communities including the backward classes and the Scheduled Castes. In the decade ending 2010, Muslims almost trebled their presence in higher education. However, this is way behind the national average of 23.6% and 22.1% in the case of backward social groups and 18.5% for Scheduled Castes. Scheduled Tribes trailed Muslims by 0.5%.

The Sachar Committee Report was released in November 2006, predicting an outcome that is now turning out to be quite true: it found double the proportion of graduates among younger Muslims compared to older ones; but it noted that the gap between Muslim men and women was widening compared with all other social groups. Besides, the report noted an almost certain possibility that Muslims will fall far behind the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes if the trend of decline in their socio-economic status is not reversed.

According to Siddiqui, Indian Muslims have to forge ahead on the basis of improving their educational and employment status. “They realise the importance of education and therefore you see an increasing number of schools inside Muslim ghettos and their higher presence in government and private schools,” she says.

However, the latest National Education Policy or NEP is a matter of concern, for it attempts to eradicate the contribution of all important education committees since 1944, including the Kothari Commission and others. These committees had recognised the importance of education for the uplift of marginalised communities, women and working children for decades, but the latest NEP pushes India back several decades by proposing an outdated language policy. Not having English language taught formally in schools, will, as Siddiqui says, “further alienate the underprivileged from both the more educated in their society as well as the world at large as schools are usually the only institutions where the poor have access to English”.

“The division of society along class lines is a negative feature of extreme ideologies like Hindutva or the fascist regimes like Hitler’s, where an intolerance of the underprivileged is promoted,” she says. The growing intolerance in India, evident from the uptick in lynching of Muslims, most of whom were poor cattle farmers, is known all over India and the world. “The rewriting of history to eliminate Muslim contribution to building India is another dangerous trend that aims to relegate Muslims as ‘outsiders’. It is not [bad] enough that they are labelled as ‘invaders’ and therefore not a part of India,” says she.

It is also a fact that Muslims face multiple challenges while seeking an education, whether in public or private institutions. In her book, Mothering a Muslim, Nazia Erum noted how Muslim students are plagued by social biases from a very young age. Erum spoke with a “varied bunch” of Muslim mothers about their school-going children, but most of them told her the same story: “They were worried and fearful for their children, many of whom were targets of Islamophobia and [hyper]nationalism in their classrooms and playgrounds,” she says. “I was shaken by their stories,” Erum says. “I was advised not to print my findings, lest I become a target of bigotry… But the large-scale incidence and under-reporting of the subject worried me immensely,” she says.

Erum found that in 85% of the over 100 cases she looked into, children had been bullied, beaten or ostracised at school because of their religion. “Even after I completed my research, I kept hearing more and more such stories from across the country. And yet we don’t speak of it openly even within the Muslim community. The malaise is growing but not too many people know about it as the victims’ parents talk only to their circles of friends and family—rarely to the school and media,” Erum says.

Notwithstanding the challenges from within and without, including the fear of further subjugation by the government, Muslims are trying to work on the basics. They are opening new schools and colleges in almost every part of the country. They are launching coaching centres for preparing their kids to qualify for NEET and JEE, besides preparing graduates for civil services. While these may seem like baby steps, they are already producing results. It is surprising and welcome to see such initiatives in the midst of maddening incidents like their deprivation from the historic Babri mosque, the preoccupation with punishing Muslims for their personal law and the abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir.

Dr Hanif Lakdawala, assistant director, Akbar Peerbhoy college of Commerce & Economics, Mumbai, tells me that Muslims will have to revive education and entrepreneurship to move away from ghettos and backwardness. They are, he points out, an entrepreneurial social group and have a huge network of institutions including madrasas. “Unfortunately, they… adopted the capitalist model of focusing only on profit. The result is obvious; the entire community is seeking rather than providing help; their focus is on dependency rather than self-sufficiency,” he says. The future, as he says, can be bright only if the vision is bright and progress-oriented too.

The author is a writer and columnist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.