Hindutva’s Anti-Dalit Aggression and Upper Castes’ Hegemony Over National Political Alternatives in India

Image Courtesy: Countercurrents

Hindutva’s caste agenda is by now fairly obvious. On the one hand, there are symbolic gestures. A Dalit is the nation’s president, and ritualised appropriation of Ambedkar has become routine. On the other hand, autonomous mobilisations of Dalits are being aggressively targetted.

The attack, which became evident from canards about Rohith Vemula’s suicide, was followed by police action against Bhim Army leader Chandrashekhar Ravan in Saharanpur and rioting against the Bhima Koregaon gathering. At present, it has taken the form of hundreds of police cases against Dalit youths in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan for spontaneous protests on April 2 against the recent Supreme Court judgment diluting provisions of the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act. Western UP and northern MP also saw physical attacks by locally dominant OBCs groups on Dalits.

Dalit politicians and masses are responding to this aggression in different ways. Ms Mayawati has given clear signals of an electoral alignment with the Samajwadi Party, until now the main rival of her Bahujan Samaj Party in UP, to counter the BJP. On April 28, in Una, in the very heart of the successful Hindutva laboratory of Gujarat, more than 300 Dalits, including families of men beaten by cow vigilantes last year, converted to Buddhism.

Isolating and attacking autonomous Dalit mobilisations is a key aspect of the Hindutva strategy. It is meant to arrest developments of Dalit politics beyond the framework of Poona Pact between Gandhi and Ambedkar meant to keep Dalits within the Hindu fold through reservations in elected assemblies and government jobs.

However, Hindutva’s anti-Dalit tactic is also the assertion of a deeper political undercurrent in Hindu society. This current is the hegemony of Savarnas, namely the three dwija castes (Brahmin, Kshatriya, and Vaishya) over the national political alternatives in India.

The national political alternatives in bourgeois nation-states can be broadly divided around three core programmes.

The centrist programme – best suited for liberal politics – aims for a national coalitional arrangement without disturbing the existing social and economic hierarchies. In India, the centrist core has largely been occupied by the Congress. For many decades, its programme and ideology were dominant, defining the character of India’s freedom movement and its nation-state institutions. The two other national alternatives — a Right-wing Hindu nationalism that aimed to develop Hindus as a political community without any internal reform, and the Left project that worked through class contradictions — were no match for the domination of Congress politics and ideology.

The size and diversity of India means that national-level alternatives do not occupy the political space fully, and there is enough room for diverse regional and community-specific political formations. The latter have often emerged from socio-political agitations around specific demands. Many of them at their regional and community level challenge Hindutva, and even in the last elections got almost as many Hindu votes as the BJP with its allies.

Upper Caste Hegemony in Modern India

A key insight of Gramsci was that ruling groups create hegemony by successfully projecting their particular interests as universal. Savarna caste Hindus have enjoyed this sort of hegemony for almost the entire duration of the modern period in India. However, certain unique features of this hegemony need to be noted.

In the era of democratic politics, this hegemony cannot rely on an explicit espousal of caste hierarchy. Nationalism of one form or another has been the preferred discourse of this hegemony. With the secularisation of caste and intensifying conflict over limited resources, Savarna caste privileges are now justified in the name of ‘merit’.

Savarna caste consciousness is articulated chiefly as intense antipathy towards mobilisations of other castes for equal opportunity. Their caste consciousness needs to be distinguished from that of dominant peasant castes (Marathas, Yadavs, Jats, Patels, etc). Also, for the reproduction of their social power, Savarnas do not need to practice open violence against Dalits, as many OBC groups in rural India still do.

It is a tragedy of modern India that none of the national political alternatives have confronted the living ghost of caste. While the liberalism of the Congress may display awareness about the degradation of oppressed castes, it does not notice the anti-democratic imprint of caste on the entire Hindu society. It imagines caste simply as a relic, and would rather wish it away, than confront it. The Left has believed in a simplistic notion of class solidarity, without getting the truth of Ambedkar’s insight that caste is a division of labourers too. In effect, both the liberalism of the Congress and the class politics of the Left invisibilised the Savarna caste hegemony, and have been integrated into the workings of this hegemony. This has weakened their ability to fight Hindu majoritarianism.

Communalisation of Savarana Castes

The growth of Hindutva is the best window to the changing ideological world of Savarna castes. For many decades after independence, the party of Hindu nationalism had remained confined to sections of Savarnas, even while the majority from these castes was voting for the ‘national’ project of the Congress. A key event in Hindutva’s growth trajectory occurred when it became the common political sense of the Savarna castes. This happened when the Congress formula of broad coalitions of social groupings unravelled in the absence of charismatic leadership, and it was unable to counter Mandal mobilisations by dominant rural castes. A ‘Hindu Rashtra’ with its appeal to Hindus united as a political community was a safer bet for Savarnas than contingencies and exigencies of diverse social coalitions in different parts of the country. In any conception of a great, ancient, spiritual India soaked in Hindu religiosity, Savarna Hindus are more than likely to be taken as its natural leaders. The Savarna castes now overwhelmingly vote for the party of Hindutva.

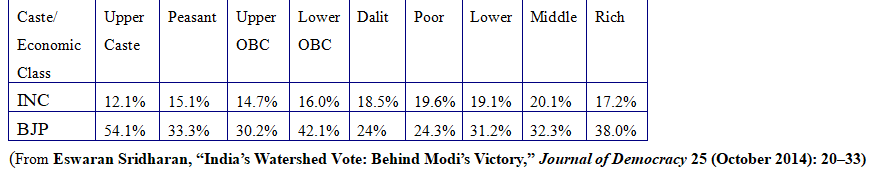

As the attached table shows, the percentages of votes received by the two significant national alternatives, namely the centrist Congress and the Right-wing BJP, is a direct reflection of the caste hierarchy.

Congress got 19 per cent of total votes to 31 per cent for the BJP in 2014 elections. This means that an average Indian who voted for either of the two parties was 60 per cent more likely to have voted for the BJP than the Congress. Among Dalits, the Congress received 18.5 per cent of the votes, while the BJP got 24 per cent of the votes, which means that a Dalit who voted for either of the parties was 30 per cent more likely to have voted for the BJP. Hence, even while going with the overwhelming flow towards the BJP, Dalits as an aggregate were trying to hold themselves back. Among the so-called ‘upper’ castes, 54 per cent voted for the BJP to a measly 12 per cent for the Congress. Hence, an ‘upper’-caste voter was 450 per cent more likely to have voted for the BJP than the Congress. The BJP got the largest share of its votes and seats from the Hindi belt states of Northern India. It is reported that up to three-fourths of the ‘upper’ castes voted for the BJP in these states.

Percentage of voters from a caste/economic class voting for a party

Interestingly, the strong antipathy towards the Congress along the axis of the Hindu caste hierarchy is not seen along the economic class hierarchy.

The percentage of voters for the Congress in all four economic classes (poor, lower, middle and rich) is close to the percentage for all voters (the highest being 20.1 per cent for the middle and the least is 17.2 per cent for the rich).

The preference of the rich for the BJP is nearly double their preference for the Congress (38 per cent to 17.2 per cent), but is in no way as high as for ‘upper’ castes.

Among all sections of Hindu society, no section votes as overwhelmingly for the BJP — and conversely, as sparingly for the Congress — as the Savarna castes.

In Hindu society, caste is a ready-made, ‘for itself’ social grouping with a well-defined identity. It can be readily adapted for the political consolidation of oppressed castes in the electoral arena.

Hindutva is a political programme of reactive traction against the democratisation of castes. It would not have gained political success if only the Savarnas moved to its fold. Its “genius” lay in using the fragmentation principle of caste against its electoral democratisation. Briefly, any caste which mobilises itself politically also excludes others. Hindutva has used the mass religiosity of Hindus to create a political coalition of smaller, left-out castes and united it with the hegemony of Savarnas in the modern sectors of society. It is a very specific configuration of caste groups with Savarna castes at its centre. However, given its uniqueness, it can also unravel easily: as it nearly did in the recent Gujarat elections.

Nothing challenges the civilisational, religious and moral premises of this configuration as starkly as a radical Dalit.

The vision of equality and freedom that animates a Rohith Vemula or a Jignesh Mevani is completely foreign to the caste mentality of Savarnas. Men and women like them stand outside caste. Yet the image of caste they project in the mirror of their radicalism cannot be wished away because they are also products of caste. Their radicalism touches a raw nerve. This is the reason behind the hatred of Hindutva towards the autonomous Dalit movements.

Sanjay Kumar teaches Physics at St Stephen’s College, Delhi University.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.