Eating With Hope: Solidarity Initiatives are the Alternative for Brazil’s Hungry

The abandonment of policies to combat poverty has put Brazil on the path back to the United Nations Hunger Map. While the UN has officially not included the country in the map, Brazil is already performing poorly in several food security indices.

7.8 million jobs have already been lost due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic served to exacerbate an already precarious situation.

According to data from Freie Universität Berlin, 125.6 million Brazilians suffer from food insecurity. The number is equivalent to 59.3% of the country’s population.

“We wake up with no hope of having bread and rice, and go to sleep without knowing if we will have something to eat the next day,” says Jaqueline Félix, from São Paulo, who used to be a domestic worker and a sales clerk, but gave up looking for a job.

22-years-old Jaqueline receives R$375 (Approx USD 70) as emergency aid from the government and depends on donations to survive. “A package of diapers or a bale of milk costs R$50. It often doesn’t fit in the budget,” she says.

Jaqueline and her two children survive on two meals a day: breakfast and a late lunch, which serves as dinner as well.

Since the onset of the pandemic, Jaqueline and her sons can only eat twice a day. Photo: Pedro Stropasolas

Brazil was once the gold standard

Things were different in Brazil once. When he took office in 2003, One of the primary goals of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Workers’ Party of Brazil was to guarantee that everyone in the country had three meals a day. However, just a few months before, a United Nations report had said the hunger was worsening even as the Brazilian state had no strategy to address it.

Lula’s response was the Zero Hunger program, which targeted four central elements related to food security. The first two were demands that had been consistently raised by people’s movements: availability and access to food.

The third aspect was stability. “This refers to the maintenance of all of this. It was not a discussion on just giving a basic basket,” notes economist Walter Belik, one of the program’s creators and a retired professor from the Institute of Economics at the State University of Campinas (Unicamp). The other key issue at the center of these debates was the quality of food.

Thanks to the program and policies to increase the minimum wage and income distribution, Brazil left the Hunger Map in 2014. “Statistically speaking, only a small number of families experienced hunger in the past decade,” explains Belik.

Survival Row

For Emerson Pavão, 50, who used to work as a security guard, the achievements of that time are in the past. As he was unemployed, he had to leave the house where he lived and has been spending nights in hostels in São Paulo for nearly a year.

“Some NGOs bring us lunch, but not every night. And there comes that time when you are forced to humiliate yourself – to go to a stranger and say: ‘I am hungry.’ Many are sympathetic, but others treat you as if you were a mongrel,” he says.

One of the most important spaces for food donation in the city is the Companhia de Entrepostos e Armazéns Gerais do Estado de São Paulo (Ceagesp).

“It’s the survival line,” says Sônia de Jesus, 55, referring to Ceagesp. She lives with her son, an economics graduate who is unemployed. She was a domestic worker and caregiver for the elderly until the beginning of 2020 when she was laid off.

Before coming across the donations at Ceagesp, the moment of opening the refrigerator was one of the saddest of the day. “There was only water,” recalls Sônia, who receives R$150 as emergency aid. “Ten years ago, I used to fill my cart at the market. Today, I leave with a small bag,” she adds.

A woman outside Ceagesp, one of the most important spaces for food donation in São Paulo. Photo: Pedro Stropasolas

Food is a priority again

Sociologist Herbert de Sousa, known as Betinho (1935-1997), was one of the icons in the fight against hunger in Brazil. Twenty-eight years ago, he created the NGO Ação da Cidadania (Citizenship Action), which has local committees in every State and organizes communities in the fight for social rights.

The NGO’s initial plan was to collect and distribute food. However, the achievements of the Zero Hunger program led to Betinho’s successors expanding their horizons.

“When I joined Citizenship Action in 2010, we were already working with the issue of ‘book hunger’ and ‘citizenship hunger’,” says Ana Paula de Souza, advocacy coordinator of the NGO.

However, the food crisis emerged again in 2017. Constitutional Amendment 95, approved that year, froze investments in the social sector for 20 years. The amendment was approved by Michel Temer who took office after the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff (PT), Lula’s successor. “People’s restaurants and community kitchens were closed all over Brazil,” says Ana Paula.

The impact of this was most strongly felt as COVID-19 hit Brazil. “Health and food security were put at risk during the pandemic, exactly when people needed to have strong immunity,” she explains.

Dehydration

The dismantling of public policies to fight hunger began during the Dilma administration. “The political situation was unstable, and a perspective of austerity, of cutting public spending, began to be adopted,” recalls Walter Belik.

With the parliamentary coup of 2016, Rousseff was replaced by Temer, and the budget suffered even deeper cuts. The impact on hunger was immediate. According to the 2017-2018 Household Budget Survey (POF), food insecurity saw an increase of 33.3% compared to 2003 and 62.2% compared to 2013.

Today, in the middle of the pandemic, even those who receive a minimum wage at the beginning of each month struggle while shopping at the market.

Take the case of Vera Lúcia Silva dos Santos, 66, who lives in the São Judas neighborhood. “We pay R$3 for a lettuce stalk, which is absurd. Eggs used to be among the cheapest items but we don’t buy them anymore. And don’t even mention meat,” she laments, while she waits in the sun for the donation of fruits and vegetables. Since 2019, she has frequented the line at Ceagesp.

Line outside Ceagesp, one of the most important spaces for food donation in São Paulo. Photo: Pedro Stropasolas

More and more elementary needs

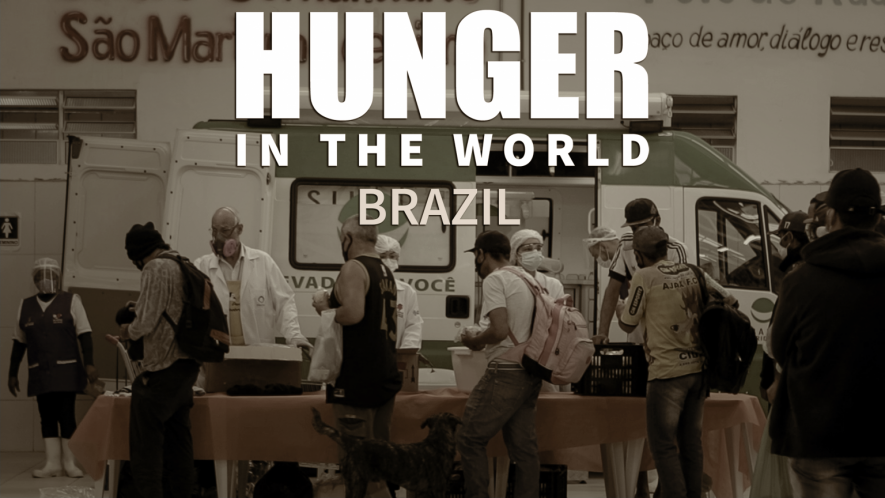

Father Julio Lancellotti is one of the people responsible for food distribution in the large shed of the São Martinho de Lima Social Center, located in the Belém neighborhood in São Paulo. According to him, there is a stark increase in misery.

In times of the pandemic, with 14 million people looking for work, even basic necessities are difficult to access. “People are constantly looking for cooking gas. It is an indicator of the humanitarian crisis – many have had to go back to making food with ethanol and many can’t even do that, because alcohol is very expensive,” he says.

Luzia Janaína da Cunha is a domestic worker who lost her job during the pandemic. She lives in a hostel in São Martinho and often starves. “I can’t even pay R$25 for a package of rice [5 kg] as I’m not working anymore,” she says.

Walter Belik estimates that 60 million Brazilians, or 27% of the population, depended on solidarity to feed themselves during the pandemic. In his evaluation, the problem could be alleviated with investment in regulating stocks.

“When prices skyrocket, the government could act to increase supply and lower the price. When the price is very low, causing losses to farmers, the government can buy stocks in order to sustain the price,” he explains.

The Food Purchase Program (PAA) provided for regulating stocks based on family farming purchases and used it to supply daycare centers, schools, and hospitals. In 2014, the program’s budget was over R$ 1 billion, but it fell by almost 90% after Dilma’s departure.

Sônia de Jesus believes that the food insecurity that affects her family is linked to the dynamics of agribusiness. “Brazil is rich in food, fruits, vegetables, but it exports a lot,” she comments, based on what she learned from her son, who is an economist.

The senses of solidarity

The advocacy coordinator of Ação da Cidadania, Ana Paula, points out that donations are important, but do not solve the structural problem of hunger.

“It is one thing to give a basket of basic food items to a person who needs help at a specific moment. It’s another thing when more and more families end up in a permanent situation of having to depend on such systems for food,” she points out.

Father Lancellotti reflects on his own role in a dialectical way. “With one hand we give bread, and with the other hand, we fight. I cannot ask those who are hungry to wait for the revolution, for social transformation and social justice. I would die if I had to wait until then. So I have to keep fighting and cannot lose sight of the horizon,” says the religious leader.

Father Julio Lancellotti is one of the people responsible for food distribution in the large shed of the São Martinho de Lima Social Center, located in the Belém neighborhood in São Paulo. Photo: Pedro Stropasolas

One of the most wide-ranging solidarity campaigns in Brazil is Periferia Viva, organized by militants from organizations such as the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST) and the Movement of Workers for Rights (MTD).

By providing healthy food which is grown on the basis of sound agro-ecological principles, peasants help fight hunger and open a debate in society about agrarian reform and food sovereignty.

Lancellotti, who is always working with the hunger-stricken, says Brazil needs to inaugurate a new cycle of hope. “I feel that the people are very tired. They can’t take it anymore. There is a hunger for both food and for a sense of life,” he emphasizes.

“If people eat the little they have while sad and anguished, it doesn’t sustain them. People need to eat with hope.”

Hunger in the World is a collaborative series produced by ARG Medios, Brasil de Fato, Breakthrough News, Madaar, New Frame, Newsclick and Peoples Dispatch.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.