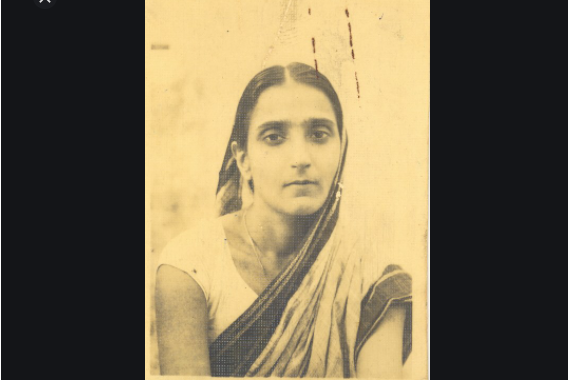

Durga Devi, an Indomitable Revolutionary

Image Courtesy: The Better India

In popular memory, the story of the Indian revolutionary movement during the colonial period is largely a story of daredevil acts of heroic men such as Bhagat Singh, Chandra Shekhar Azad and others. A significant number of women in the revolutionary movement, though their contribution is no less, are largely seen as associates or aides of the male revolutionaries.

The famous revolutionary Durga Devi Vohra, a.k.a. Durga Bhabhi, is portrayed in film and popular narratives as the woman who helped Bhagat Singh escape Lahore after the assassination of superintendent of police John Saunders. The focus of this narrative is Bhagat Singh, naturally, for his heroic role in the freedom movement can subsume all other revolutionary narratives and acts. Besides, extraordinary events and spectacular acts tends to have greater recall value, relegating to the background the everyday activities that go into revolutions, making them seem banal. For understandable reasons, the revolutionary movements are remembered through the Kakori incident, the assassination of assistant police superintendent John Saunders, the revenge for Jallianwala Bagh and the Assembly bombing.

Before these narratives, even the ideology and beliefs of the revolutionaries young or old, which motivated them to action, can be sidelined. As well, there is a gender bias in public memories and imaginations of the revolutionary movement. Women revolutionaries such as Kalpana Dutta, Pritilata Waddedar and Durga Devi undertook spectacular acts, and planned and executed them independently, have not dented the popular arena.

Durga Devi Vohra was born on 7 October 1907 in a considerably wealthy family of Allahabad and was married to Bhagwati Charan Vohra, a future revolutionary ideologue and organiser of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) set up in 1928. Educated mostly in religious scriptures as a girl, she was encouraged by her husband to study, who arranged for her to be taught at home. She later graduated from Panjab University in Hindi with honours and took up a teaching job in Kanya Vidyalaya. This job, in her own words, “allowed her to move freely and ward off police suspicion regarding her role in revolutionary activities”.

Though already suspected of being involved in political activities—also because she was married to Bhagwati Charan—Durga Devi’s initiation in revolutionary politics truly began in 1926, with the formation of the Naujawan Bharat Sabha (NBS), a mass organisation to mobilise students and the youth of Punjab. In the traditional Indian way, it was Durgawati Devi and the foster sister of her husband, Sushila didi, who inaugurated the founding meeting of the NBS by sprinkling their blood on the curtains which had covered the portrait of Kartar Singh Sarabha, a Ghadarite and hero to the revolutionaries, who was executed in Lahore in 1915 at the age of 19.

Even though women were part of the revolutionary movement their role was defined within the “private sphere” of revolutionary politics, i.e. they were chiefly involved in liaising, acting as couriers and messengers, and moving weapons, apart from being the caregivers to male revolutionaries. On the other hand, actions in the “public sphere” of the movement, such as assassinations, bombings and so on, were exclusively a male forte. Durga Devi, till Bhagwati Charan was alive (he died in 1930 while testing a bomb), was mainly engaged within the private sphere, running errands, campaigning among women, but she also helped run his bomb-making factory.

After 1930, she transitioned decisively to the public realm. As Kama MacLean, a professor of South Asian and World History at the University of New South Wales writes, “Durga Devi’s widowhood did not drive her into melancholy seclusion; if anything, she became more active than before.” She kept pushing for more and more involvement in the movement and party and engaged in several arguments with Azad, who then headed the HSRA.

Manmath Nath Gupta, a comrade of Azad and Durga Devi’s recalled in an interview, “Azad’s appreciation for Durga Devi’s (and Sushila didi’s) work led him to revise his views about women in the revolutionary movement on the basis that they faced a “double danger from the police”. Azad later trained several women revolutionaries in armed actions and the organization opened itself to recruiting women.

Durga Devi and her comrade Dhanvantri later took charge of organising the party in Punjab after the arrest of Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev. After the death sentence was announced for Bhagat Singh, Shukhdev and Rajguru, Durga Devi and Ghadarite revolutionary Prithvi Singh Azad and HSRA member Sukhdev Raj attempted to assassinate the governor of Punjab Sir William Hailey in Bombay as retaliation. But due to high security around the governor, they had to change plans and on the midnight of 8 October 1930, the three fired some twenty shots from a car on a British couple at Lamington Road police station, injuring sergeant Taylor on his hand and his wife on her leg. Durga Devi had fired some three or four shots at them and slipped away, undetected. The presence of a woman was noticed by the colonial administration and the incident was described in the Bombay [now Mumbai] press as the “first instance in which a woman figured prominently in a terrorist outrage”.

After her escape, Durga Devi concerned herself with the release of political prisoners. In many a ways, her activism became synonymous with the issue of political prisoners and she became the centre of HSRA’s activity as far as the release of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, Rajguru and other revolutionaries was concerned. She also led the funeral procession of Jatindra Nath Das, who died after a historic 63-day hunger strike demanding the rights of political prisoners in Lahore Jail on 13 September 1929.

As many revolutionaries were on the run, and several others were under constant surveillance, it was left to Durga Devi and her comrades to liaison between jailed revolutionaries and the party and coordinating with their lawyers.

She was one of the main organisers and campaigners of the Bhagat Singh Defence Committee, which campaigned for the release of revolutionary political prisoners, selling her personal possessions to meet the campaign costs. She met Mahatma Gandhi twice, first in 1931 to persuade him to include the release the revolutionaries as a condition in his negotiations with Viceroy Irwin, and then in 1938 to campaign for the inclusion in his campaign to release two of her comrades jailed in the United Provinces, which at that time had Congress government. Both times, she was disappointed with Gandhi’s response.

Due to constant police surveillance, and with the HSRA in total disarray by 1932, Durga Devi decided to surrender. She was imprisoned for six months and released with orders for externment from Delhi and Punjab for three years. She moved to Ghaziabad and taught in Pyare Lal Girls School for two years, after which in 1938 she moved to Lucknow and was engaged with the Indian National Congress for some time. She was invited to contest elections, which she refused, and concerned herself largely with preserving the memory of revolutionaries, mostly removed from public gaze.

In Lucknow, Durga Devi started a school for underprivileged children, which is now the Lucknow Montessori Inter College. She established the ‘Shaheed memorial and independence struggle research centre’, under whose efforts various documents related to revolutionaries were collected and published for the first time. As one of the most authoritative chroniclers of Indian revolutionaries, Sudhir Vidyarthi, informs, Durga Devi made it her goal to “collect literatures related to revolutionaries and revolutionary movement for the sake of future researchers”. She also wanted to build a martyr’s memorial, a dream which remained unfulfilled till she was alive.

In 81 years of public life, Durga Devi began as a home-maker, got involved in political activity, became a revolutionary in her own right, and finally became educator and institution-builder. She defied the traditional gender norms and roles. She died on 15 October 1999, in Ghaziabad. Vidyarthi has written of her last wish: to have the Indian National Army’s band, led by Captain Ram Singh, to play on her death. For, she believed, “aashiq ka janaza hai zara dhoom se nikle”!

The author is a research scholar at JNU. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.