Decoding Budget Numbers and Words

Since Piyush Goyal tabled the interim budget before parliament earlier this year (February 1, 2019), the Lok Sabha elections giving the Modi government an almost certain additional five years in office is not the only development. In addition to the reality of deepening agrarian distress and grim employment situation that were known even then, at least three other mutually related hard facts relevant to the finalisation of the budget for 2019-20 have also become known since, being acknowledged even by the Economic Survey. The first is the undeniable and widely recognised onset of a slowdown or weakening of demand conditions in the economy. Second, the major shortfall in the actual tax revenue receipts of the government in 2018-19 – by Rs 1.68 lakh crores compared to the Revised Estimates, which were themselves 0.23 lakh crores less than the Budget Estimates. Finally, the indication that revenue prospects of the government are becoming even bleaker – gross tax revenues from all central taxes in April-May of 2019-20 showing a mere 0.22% increase over the same period last year.

FROM INTERIM TO FINAL BUDGET: CONTINUITY and CHANGE

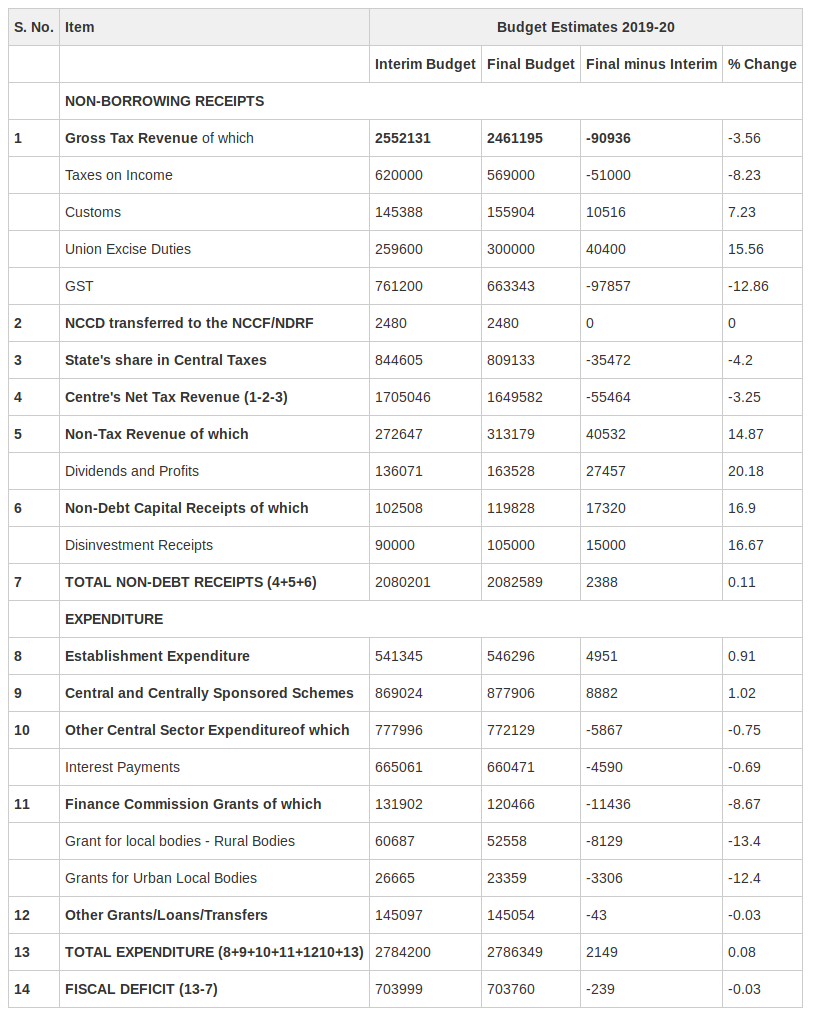

If the first speech of the Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and the actual measures and figures of the final budget for 2019-20, reflected in any way the gathering clouds of economic uncertainty, it certainly didn’t do so overtly. If one compares the interim and the final budgets for 2019-20 (Table), one would find very little difference in the total figures of non-borrowing receipts and expenditure of the government and therefore also of the fiscal deficit or the borrowing requirement. Seen in aggregate terms, this means that there is nothing that could be described as a fiscal stimulus. Going beyond aggregates, however, reveals important changes in the composition of both the receipts and expenditures.

Also Read: Some Disquieting Trends in the Budget

On the receipts side, the final budget clearly makes a shift towards placing a greater reliance of non-tax sources of receipts as compared to tax revenues. Thus, the projected earnings from gross tax revenues to be shared between the Centre and the states have been slashed by Rs 90,936 crores as compared to the interim budget, while non-tax revenues and non-borrowing capital receipts are to go up by a combined sum of Rs 57,852 crores. These additional resources are expected to come from a greater extraction of the surplus earnings of public sector enterprises, banks and the Reserve Bank of India on the one hand, and higher disinvestment receipts on the other. Further, if realised, these may compensate the central government for the loss of its share in tax revenues (Rs 55,464 crores), but not for the loss states will have to bear of Rs 35,472 crores.

Looking further, within tax revenues, it is the projected receipts from GST and income taxes that have been cut down relative to the interim budget, by more than the reduction in total revenues. These cuts are partly by compulsion and partly by design. Actual revenue realisation of both GST and income tax revenues in the previous two years have fallen far short of the projections, and the trends for the first few months of the current year also show that the interim budget estimates for 2019-20 were also way too optimistic. Since no measure is actually envisaged or expected to raise revenue realisations, and the supposed additional tax on the super-rich is a piecemeal measure, continuing with the estimates of the interim budget was untenable. So, with the government’s showcase indirect tax reform and demonetisation failing to deliver on their promises, Nirmala Sitharaman has turned to customs and excise duties to find more revenue – and most of this will be through the additional taxes on petrol and diesel (POL taxes). Heavier POL taxes taking advantage of the fall in international oil prices had really been the only additional source of revenues in the first term of the Modi government – now that the elections are over, it has turned once again to the same source even though international prices are now much higher than what they had fallen to earlier.

On the expenditure side, even the apparent increase in expenditure on schemes is marginal, and the increase in expenditure on this head and the establishment expenditure of the government will be mainly compensated by cutting grants to local bodies, both rural and urban. Regarding expenditure on schemes, experience shows that if revenues and receipts are inadequate, requisite cuts will be made to these expenditures. This happened in the last year too and had the budget provided provisional final figures rather than the original revised estimates of the interim budget, it would probably have revealed that the actual expenditure on central and centrally sponsored schemes in 2018-19 was less than that in 2016-17.

Also Watch: Union Budget: Who Gains, Who Loses?

In the final analysis then, what can the final budget of 2019-20 claim as its achievements? Imposing an increased burden of taxation on the common people, parasitically feeding on the assets of the public, and imposing cuts on expenditures at lower levels of government that could have benefitted the people – and all of this to barely hold up the finances of the central government. Even this might not result as the underlying economic realities may result in revenues being less than projected, and further expenditure compression being imposed to meet fiscal deficit targets. The budget does nothing to address those realities – neither the immediate problem of weakening demand or the longer-term structural inequalities underlying this – except aggravating them. All hope has instead been pinned on talking the economy out of the crisis by promising a rosy future to domestic and foreign capital – in the form of more reforms as their reward for failing to deliver for several years, private investment and export growth-based development, despite all the efforts to increase the ‘ease of doing business’, or programmes like Make in India and Start Up India. This evidence and the knowledge of slowing consumption growth and of excess capacity or production in several sectors, common sense would lead to the conclusion that private investment at present is even more likely to be held back by the problem of weakening demand instead of being its solution. This common sense, however, has no reflection in the budget. Instead, the budget and all the extra-budgetary talk are together are an indication that the government has read the electoral verdict as a sanction for actively tilting the balance in the economy further against the common working people and in favour of big private capital – that repeatedly tried and failed method is the only form in which there has been any attempt to stimulate a flagging demand situation

Union Budget 2019-20, Final Versus Interim (Values in Rs. Crores)

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.