Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya: A Centenary Salute to Multifaceted Philosopher

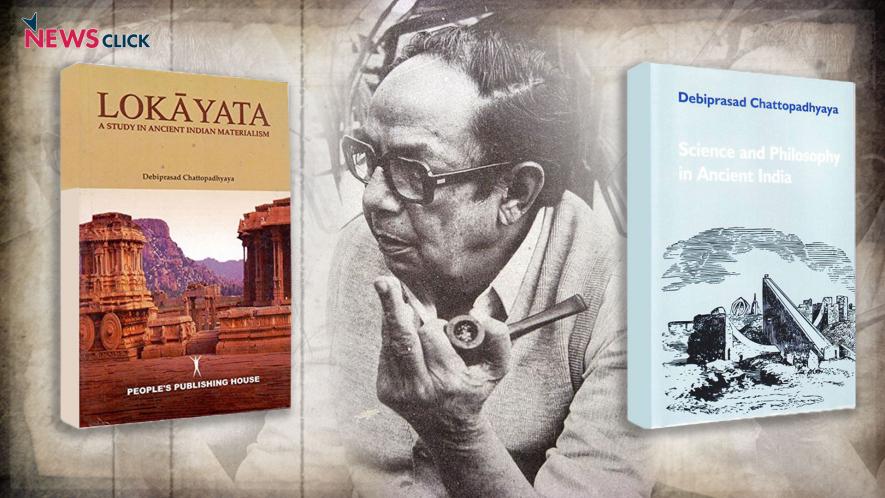

Newsclick Image by Nitesh Kumar

It is ironic but true. The internationally known philosopher, Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya, referred to as ‘Philosopher of Secularism’, in a glowing tribute to him on his death in 1993, by none other than the Marxist leader EMS Namboodiripad, is not remembered as he should be countrywide, even in this centenary year when he is most relevant today. This is particularly true in view of the fact that the country is seeing almost a ‘do or die’ battle between the forces of secularism, scientific temper and the mumbo-jumbo of ‘godmen’, and forces of Hindutva and right reaction striving to take India back to the dark ages. It is equally true that in some states, with Bengaluru in Karnataka taking the lead, followed by Andhra Pradesh and the recent meeting in Kolkata (West Bengal) by the Asiatic Society, some initiatives have begun.

Fortunately, the city of Kolkata has woken up from the slumber but has planned two major celebratory functions on November 19, his birthday. According to reports received, the centenary celebration of Chattopadhyaya is being celebrated in Kolkata both at the Asiatic Society and at the cultural hub of Nandan. The Asiatic Society is organising a two-day seminar-cum-workshop in collaboration with the All India People's Science Network (AIPSN) on “Contribution of Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya in Understanding Science and Society in Ancient India". The keynote address willbe delivered by noted scholar Prof. Ramkrishna Bhattacharya. The other speakers include Dr. P. Rajamanikklayam, General Secretary of AIPSN, Dr. Arunava Mishra, Dr. Satyabrata Chakravarty, General Secretary and Prof Isha Mahammad, President of the Asiatic Society. Chattopdhyaya’s daughter Aditi Chatterjee will present her personal reminiscences.

Anushtup Publication is organising a seminar at Nandan, the cultural hub in Kolkata on November 19. The speakers would include noted scholar and feminist writer Gayatri Chakrabarty Spivak, Professor of Comparative Literature and Society at Columbia University, poet and litterateur Shankha Ghosh, who is respected not only for his poems but also for his fearless criticism of what is wrong in the contemporary political arena.

What indeed struck me as a journalist who has interacted with Chattopadhyaya in more than brief interludes, including getting articles from him, is that he could write on almost any subject, with a polish that could put many journalists, philosophers, sociologists and of course even lovers of scientific temper to shame. He was an all-rounder. Besides being a specialist in philosophy, he could dabble in poetry, especially during his early youth when he edited, along with his elder brother, Kamakshiprasad, the Rangmasal journal for young readers, as also wrote articles, novels and short stories and even bring out his own journal. Ramkrishna Bhattacharya, the writer of ‘What is Living and What is Dead in Indian Philosophy’, who was also Chattopadhyaya’s friend says, “He is best known all over the world as the explicator of materialist philosophy in India and his creative contributions to Marxism. His magnum opus is Lokāyata (1959)

Later, in another interlude with him, I discovered that he once took on the then chairman of the Communist Party of India (CPI), SA Dange, and got him censured on a question over the philosophical writings of his daughter, Rosa Deshpande, which Dange supported, as it would have helped the dark forces of reaction. Of course, the matter was thoroughly debated within the CPI. The late professor and parliamentarian, Hiren Mukherjee, among others, backed Chattopadhyaya. It was a marathon meeting of leading lights of the CPI that was marked by heated debate and finally a vote.

One of this writer’s interludes with Chattopadhyaya took place in his own flat close to in SN Pandit Street. way back in the early 1980s. Those were days of hectic power cuts. I was greeted by a rather jocular professor, drowned in a sea of books, both Bengali and English, virtually acting as walls. He later sent me his stray thoughts in the form of an article after that meeting, which displayed his journalistic flare and passion.

He wrote, “The hands shake when picking up the morning paper. The hands shake while tuning the radio or TV for the evening news. How much of murder and malevolence can one listen to? I need not be told, of course, that the problems involved are too complex to offer any ready solution, nor about how the administrators and other are proposing to tackle these. But, I am anxious to mention another thing, where I feel being somewhat personally involved. My head hangs low in shame when I read in the newspapers about a million people congregating in pilgrimage where an innocent girl was burnt alive just to keep company with her dead husband. There were presumably rogues among those that organized the congregation. But the million congregated could not be all rogues. The majority in fact, the vast majority – must have considered it an act of piety, must have considered the place a holy one. In other words, they were under the spell of darkness, of mindlessness, or thought totally perverted. I do feel that I am also involved in this debauching of basic humanism. For what exactly do I owe to the people? If the vast majority of them is still being haunted by the demon of darkness and ignorance, a thinker by profession has to brave facing the demon, to destroy it.”

Chattopadhyaya added: “This, of course, is not easily done. For the demon, we are aware, works with a mask on its face. A ‘holy mask’, which the people are required to believe, is made of the wisdom of our sages-- the sastras or scriptures.” He said, “One paid by the society for thinking activity has to unmask it first. Scriptures or no scriptures, the thinker has to work for the cultivation of sanity in the people. But that is apparently a risky job. The thinker can easily be branded as a heretic, going against the mainstream of the national culture and hence hounded out of good society. Let, however, this shame be a reminder to me of how much remains to be done. Certainly not for me alone but also for my colleagues whose conscience is not debauched by careerism and job-hunting. Not that there is nothing more for the philosophers to do. But that is for tomorrow. Today is the struggle, let us above all ensure ourselves that there is actually a tomorrow.”

Sadly, the situation has not changed much today. Look what is happening in Sabarimala today. Then it was Roop Kanwar (the Sati case), today it is Sabarimala. In the name of tradition, regressive practices are often continued and are specially whipped up in election times, as today.

Realising that I was a journalist, Chattopadhyaya virtually put before me something I should know in detail about journalist, rationalist Joseph Edamaruku, just to let me know what journalistic exposures should include. He said Joseph was worth a read. Of course, he was just one of the several influence on him. Joseph was the bureau chief of a Malayalam magazine for over 20 years besides being the founder editor of a rationalist periodical in Malayalam. Chattopadhyaya said it was necessary to expose frauds called miracles, especially those of so-called ‘godmen’. Most miracles he said were just pure magic and could be scientifically demolished.

In this context, Chattopadhyaya also mentioned Abraham Thomas Kovoor (April 10, 1898 – September 18, 1978) who was an Indian professor and rationalist who gained prominence for his campaign to expose as frauds various Indian and Sri Lankan "godmen" and the so-called paranormal phenomena. His direct, trenchant criticism of spiritual frauds and organised religions was enthusiastically received by audiences, initiating a new dynamism in the Rationalist movement, especially in Sri Lanka and India. In a similar way, Chattopadhyaya, who all called Debida, felt it was necessary that miracles of the likes of Saibaba and others deserved journalistic exposures.

Philosopher of Secularism

In one of his famous columns, none other EMS Namboodiripad, who knew him very well, wrote in Frontline magazine shortly after the philosopher’s death in 1993, “Chattopadhyaya, in one of his major works ‘Science and Technology in Ancient India’ quotes the 20th century scientist of chemistry, P.C.Ray, to show that the stagnation of science and technology should be traced to Sankara’s philosophy. The same conclusion is drawn by another towering Marxist intellectual, D.D.Kosambi, from whose works Chattopadhyaya quotes extensively. This, therefore, is a powerful weapon in the hands of secular and science-oriented intellectuals and social activists in their struggle against the Hindutva and other sinister forces which want to throw India back. They repeat the canard invented by the ideologues of the colonial British rulers according to whom India has remained a land of idealism and spiritualism par excellence. In EMS’s view, Chattopadhyaya’s works provide a sharp weapon against all these revivalist and obscurantism. .

Some other aspects

It would be fair to recall what an expert like Ramkrishna Bhattacharya had to say in his tribute in 2012. “The publication of Lokayata: A study in Ancient Indian Materialism (People’s Publishing House, New Delhi, 1959) by Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya (1918-1993) ushered in a new era in the cultivation of Indian philosophy. Internationally Joseph Needham, best known for his multi-volumeScience and Civilisation in China, wrote to the author: “Your book will have a truly treasured place on my shelves. It is truly extra-ordinary that we should have approached ancient Chinese and ancient Indian civilisations with such similar results....”

Louis Renou, the then doyen of French Indologists, said: “The book is of definite value and deserves to be carefully studied by Indologists and sociologists.” George Thomson, Professor of Greek, University of Birmingham, UK, spoke of it as “the work of a creative Marxist who knows and loves his subject.” J B S Haldane in a personal communication told Chattopadhyaya : “I have enjoyed your book greatly.”

Chattopadhyaya’s association with Professor Walter Ruben began with Lokayata. Ruben was of the opinion that Chattopadhyaya’s “books are indicative of a new period of Indian investigation of Indian philosophy.” Later: ‘What is Living and What is Dead in Indian Philosophy’ (1976) explores new grounds, covering a wider area. Another turning point was: Science and Society in Ancient India’. All this should be considered in the backdrop of his chronic illness and delays in publication.

In sum, one can perhaps best remember him as a humanist, Marxist, staunch lover of reason, scientific thinking and a secularist to the core, referring to some opponents as drumbeaters who want a return to antiquity, myth and mythology. With his death on May 8, 1993, his absence to a modern progressive and secular India suffered a jolt.

Postscript

An episode sometimes narrated by him was the confusion of his name with another well-known philosopher turned educationist, turned minister, DP Chattopadhyaya. This very often took place at airports. In fact, educationist DP Chattopadhyaya was so humble that he often used to say, the author of Lokayata is unique and this confusion sometimes puts me to shame.” The author of Lokayata is unique indeed …

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.