The Dark Side of Indian Populism

One aspect of the current global populist upsurge is its dual character; it represents an anti-elitist discourse on the one hand, while also reflecting the revenge of elites against the marginalised who have gained social mobility. Populism, too, signifies a crisis of representation of the excluded alongside a reconfiguration of elites. Populists return to power riding on economic crises—like the one in the rust-belt of the United States—and growing economic inequalities. But they are also more aggressively pro-corporate. Finally, while populists in the Global North talk about saving jobs through protectionism and de-globalisation, those in the Global South speak of creating employment through greater integration with the world economy and more opening up of domestic markets.

What makes populism a unique phenomenon is it is as much about the deprived as the elites own it. It preserves the privileges of economic elites and professional middle classes by working through local cultural idioms. Populism is usually understood through the lens of how it appeals to the masses and deploys the affective dimension to mobilise emotions and everyday ethics. However, populism also needs to be closely understood through the eyes of social elites. In fact, how elites self-represent themselves determine the character and contour of populism. And in this respect, the social character of Indian populism seems somewhat contra-distinct to populism in other nations.

Compared with white Christian elites in the West or Sunni Muslims in Turkey, Indian social elites come across as a more diffident class. This could also mean that the trajectory of Indian populism is heading towards a somewhat distinct direction. While elites all over the world fight to restore and preserve their privilege, India’s social—that is caste—elites suffer from a perennial sense of loss, historical injury and psyche of victimhood. Indian elites can be said to be as diffident as, and suffering from as much lack of confidence, as Dalit-Bahujans.

Dalit-Bahujan politics did articulate the loss of self-confidence and sense of self due to caste-based discrimination, but it wrongly assumed that caste Hindus are a self-assured and socially confident group. Truth be told, India has a case of competing diffidence. There is an enduring gap between external image and self-perception of Indian elite castes and Dalit-Bahujans. Here, ritual status and rigid caste hierarchies protect and shield a weak self. At the same time, the twin processes of secularisation and modernisation disturbed these hierarchies and de-legitimised ritualistic functionality. So, what we find are diffident elites and distorted subalterns.

Right-wing populism in India is restoring space for the elites by re-ritualising the public sphere and providing the distorted subaltern a means of articulation through uncivil street-level mobilisation. Ego, manipulation, deceit, betrayal, lies, cheating, short-changing, double-speak, sadism, and mocking have helped converge the elite fear of loss of status with the desperation of the subaltern to gain social mobility. Could this make Indian populist-authoritarianism not only unique but also more long-lasting and durable compared with the world? Could populism be socially more organic in India than elsewhere, as also hold a legitimacy more social and cultural than “merely” political?

As elsewhere, Indian elite diffidence—lack of self-assurance, confusion and sense of guilt—is born out of colonialism and the caste system. However, their confusion also has to do with the porous character of Hinduism, which does not allow elite locationality. Hinduism is partly accomodative, even inclusive, but also rigidly exclusionary. It does not have an ‘organised’ character. That is why right-wing ideologues articulate a sense of discomfort with Hinduism's porous and diversified social character.

Further, the caste system makes Indian elites more socially segregated and their recognition more self-referential and divinely ordained than socially located. Modernisation—gaining English-language skills, social capital and networking,for example—entrenched these aspects, and elites were able to sustain their sense of superiority. That said, on the political economy front, Indian social elites did not become creative entrepreneurs but a contractor class and middle-men in a rentier economy—what we often refer to as crony capitalism.

The uniquely porous character of Hinduism has made it challenging to bring substantive social change or claim social superiority without guilt. The result it a guilt-ridden but stubbornly self-seeking social elite. It preserves privilege through caste networks but does not have the confidence to justify them through social means. They are aware of the need for change, but lacks any conviction or commitment. They seek to be modern but not lose their pre-modern privileges.

These contradictory processes themselves make elites unsure and socially diffident. As they negotiated these complexities over time, India witnessed tentative social mobility from below. On their part, new subaltern caste and class mobilities did challenge elite privilege but only to imitate the ways of established elites.

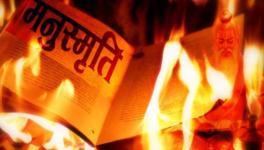

Despite the initial thrust of subaltern anti-caste mobilisations around self-respect and dignity, later generations of socially mobile subalterns had no image to reproduce but of the traditional elites. They used anti-caste symbols to question privileges but not ways of living and thinking. The process earlier manifested as Sanskritisation is currently seen as Hinduisation. India ended up in a social condition where the subaltern imitated the elites, and the elites remained socially unsure of themselves.

The subalterns attempted to restore their confidence in imitating the social elites, while the social elites continued to suffer from perennial diffidence. This phenomenon is visible in the subaltern demand for English education, but their belief that the English-educated elites are a confident social group is mistaken.

This process got further complicated through the pace of change introduced by economic globalisation and the communication revolution, which are generic challenges to cope with the pace of social and economic changes.

Right-wing populism has emerged in this somewhat unique context of a clueless elite and imitative subaltern—diffident elites and distorted subalterns. There is no effective alternative articulation even though mutual interests do not match or converge. Contradictory interests are being articulated through similar impatience, anxiety and incivility.

The current regime and its leadership are being identified for their performances and functioning style rather than content and agenda. It is the brazenness of the strongman that is seen as reassuring rather than what it is being deployed for or its outcomes. An ideal situation could have been the success of the self-respect movements from below, which could have lent elites confidence and imagination of a new way of life.

The author is an associate professor at the Center for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. His book, Politics, Ethics and Emotions in ‘New India’, will be published by Routledge, London, in 2022. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.