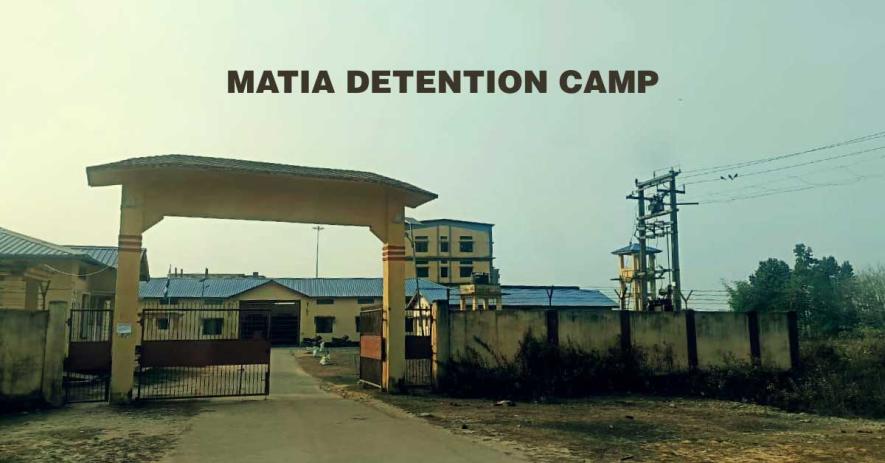

Covert Deportation at Assam’s Matia Detention Centre

In recent weeks, a significant but opaque operation has been underway in Assam involving the mass removal of detained foreign nationals — including the Rohingya refugee community — from India’s largest detention centre at Matia, Goalpara. Multiple reports emerging from Bangladeshi media and border officials confirm that at least 123 individuals, comprising Rohingyas and Bengali-speaking persons, were forcibly pushed back across the international border into Bangladesh. These deportations were reportedly executed without formal diplomatic protocols or transparent deportation procedures.

This operation starkly highlights India’s growing use of extrajudicial “pushbacks” as a tool to circumvent the complexities of refugee protection, legal detention, and diplomatic engagement. Such actions potentially violate both India’s obligations under international refugee and human rights law, as well as its own legal safeguards for stateless persons and asylum seekers. The refusal of Bangladesh and Myanmar to accept these vulnerable individuals formally has seemingly led India to adopt a policy of indirect expulsion—placing the burden of care onto its neighbours.

The scale of the deportations and the lack of public disclosure by Indian authorities raise profound concerns about accountability and due process. No official confirmation has been made public regarding the exact number deported, the legal status of these persons at the time of removal, or whether they were deported through the involvement of their respective governments or international bodies.

Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma’s public endorsement

The clandestine nature of the deportations was partially lifted when Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma confirmed that detainees—including Rohingya refugees and other declared foreigners without pending appeals—were indeed “pushed back” to Bangladesh. Sarma explicitly described the removals as a Government of India “operation” in which Assam was a stakeholder.

As per a report in Deccan Herald, May 12, Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has openly confirmed that these pushbacks are not isolated incidents but part of a deliberate and planned “operation” by the Government of India. Speaking to media in Guwahati on May 10, Saturday last, Sarma had said that Rohingyas and other “declared foreigners” without pending legal appeals were sent from the Matia detention centre to cross into Bangladesh.

“Matia is almost free now, with 30–40 people left,” he said according to Deccan Herald, indicating a drastic reduction in the population of the largest detention facility in India, without explaining the mechanisms or legality of these removals. His statement validates what activists and border watchers had feared: that India is undertaking silent deportations of stateless or vulnerable populations, particularly Rohingya, who neither Myanmar nor Bangladesh has agreed to take back formally.

His framing of the pushbacks as an operational success obscures the severe humanitarian and legal questions at stake—particularly the forced expulsion of stateless persons who have neither been formally recognised as refugees nor granted safe resettlement options. Sarma’s statement also reflects a broader policy shift in Assam and India, characterised by increasingly punitive approaches toward those labelled “foreigners,” with little regard for rights or rehabilitative processes.

What does the on-the-ground data say?

Independent data gathered by the Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP) Assam team sheds important light on the evolving reality at the Matia detention centre:

- According to local investigation by our CJP team, all but one of the Convicted Foreign Nationals (CFNs) previously held at Matia have been “pushed back” or deported, leaving only a single Nigerian national, namely Kamardeen Oaladeji Oladimeji, still detained.

- The precise number of deportees remains undisclosed by authorities; however, earlier records indicated 203 CFNs held in Matia. Excluding the one Nigerian detainee, this implies that 202 individuals have been ‘removed’ (read deported)—presumably without transparent, lawful deportation procedures. Details of those in Matia deportation centre may be read here.

- In addition to CFNs, there remain 46 Declared Foreign Nationals (DFNs) at Matia, individuals who have been declared foreigners by Assam’s Foreigners Tribunals but who currently have appeals pending in the High Court or Supreme Court.

- Importantly, our experience at CJP, through ground level investigations, notes that most DFNs are Indian citizens who have been wrongfully declared foreigners, often due to flawed tribunal proceedings or inadequate documentation. These persons should not be treated as deportable foreigners but must be reintegrated into Indian society through proper legal mechanisms.

- One case being fought in the High Court by CJP involves Ajabha Khatoun, a woman wrongly declared a foreigner who faces deportation despite her Indian citizenship claims. On March 3, 2025, the Gauhati High Court’s issued stayed the deportation of Ajabha Khatun, currently lodged in the Matia detention camp of Assam after she was arrested in September 2024.

- The CJP team’s human rights works and humanitarian work, raises critical doubts over whether these pushbacks constitute official deportations involving diplomatic channels, or instead represent unlawful forced expulsions. No public confirmation has been found that these CFNs were formally repatriated through their respective embassies or governments.

This information underlines a troubling reality: India’s deportation machinery at Matia appears to prioritise mass removals over legal protections, transparency, or rehabilitation.

The Case of the Nigerian languishing in Matia: Illegal detention and judicial intervention

In the midst of the mass deportations, the protracted detention of the remaining one Nigerian national, Kamardeen Oaladeji Oladimeji, stands as a stark symbol of systemic failure. Oladimeji has been held at the Matia detention centre for 1,457 days beyond his legally mandated sentence.

“Therefore, it is seen that by the time the order and sentence was passed, the petitioner had already served his sentence as on 13.05.2021. Thus, as on the date of this order, the petitioner has spent 1457 days in illegal detention.” (Para 3)

Convicted in 2021 for offences under the Foreigners Act and the Passports (Entry into India) Rules, Oladimeji had served his six-month imprisonment and paid the fines by May 2021. Yet the state continued to detain him unlawfully without initiating repatriation or granting release, as per a report of LiveLaw.

Recognising the gross illegality, a division bench of the Gauhati High Court issued a strong order directing Assam and central authorities to facilitate his immediate repatriation on May 9, 2025. The Court noted that failure to do so would compel it to release Oladimeji unconditionally, at the risk and cost of the state.

“The State as well as the appropriate authorities in the Home & Political (B) Department, Govt. of Assam; Secretary to the Govt. of India, Ministry of Home Affairs; and the Secretary to the Govt. of India, Ministry of External Affairs shall specifically take note of the fact that the sentence of the petitioner was served on 13.05.2021 and therefore, the petitioner is in illegal detention for 1457 days. Therefore, if the appropriate actions are not taken within the due time, the said authorities are put to notice that the Court would be compelled to release the petitioner unconditionally, which would be at the risk and cost of the said authorities.” (Para 9)

Significantly, the Nigerian Embassy has shown readiness to issue an Emergency Travel Certificate upon a video interview, which could be facilitated by the Matia camp authorities. Despite this, bureaucratic inertia and inter-agency delay have perpetuated his illegal incarceration.

Oladimeji’s case starkly illustrates the human cost of systemic indifference and the breakdown of procedural justice in India’s detention centres—where individuals are trapped beyond their sentences due to administrative paralysis and policy neglect.

The complete order may be read below.

A Legal and ethical red Line: The risk of violating non-refoulement

The secrecy and speed of deportations from Matia detention centre raise serious concerns about India’s compliance with international legal obligations, particularly the principle of non-refoulement — a norm that prohibits returning individuals to territories where they may face threats to life, liberty, or persecution.

Although India is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, non-refoulement is widely recognised as a principle of customary international law, binding on all nations irrespective of ratification. Moreover, India is a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which under Article 7 prohibits cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment — a protection that logically extends to any deportation that risks exposing someone to such harm.

Indian Constitutional courts have historically affirmed these principles:

- In Ktaer Abbas Habib Al Qutaifi v. Union of India (1999), the Gujarat High Court held that Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to life and liberty, protects refugees and asylum seekers from being forcibly returned to unsafe conditions.

- In Dongh Lian Kham v. Union of India (Delhi High Court, 2010), the Court explicitly recognised the principle of non-refoulement as part of the constitutional guarantee under Article 21.

- In Nandita Haksar v. State of Manipur (2021), the Manipur High Court permitted Myanmarese nationals fleeing a coup to meet the UNHCR in Delhi, reaffirming India’s obligations under international humanitarian law and its adherence to non-refoulement even outside the refugee treaty framework.

However, recent developments signal a regression.

In May 2025, the Supreme Court of India, while hearing petitions challenging the detention and deportation of Rohingya refugees from Delhi in the case of Jaffar Ullah and Anr. v. U.O.I And Ors, refused to stay their removal. The Court stated that the right to reside in India belongs only to citizens, and thus deportation of non-citizens did not infringe on fundamental rights. The ruling echoed earlier observations in Mohammad Salimullah v. Union of India, where the Court maintained that while non-citizens are entitled to certain constitutional protections (like Articles 14 and 21), they do not have a guaranteed right against deportation — even if the risks upon return are well-documented.

This narrowing interpretation of constitutional protections in cases involving stateless persons and asylum seekers directly undermines the spirit of non-refoulement, and sets a dangerous precedent. It opens the door for the executive to expel individuals without fully evaluating the risk of persecution, torture, or arbitrary detention — outcomes that are extremely likely for groups like the Rohingyas, or individuals expelled without nationality documents.

The situation unfolding in Assam, with individuals being pushed across the border without diplomatic coordination or legal review, cannot be seen as lawful deportation. It is closer to extrajudicial expulsion, and when applied to stateless or persecuted communities, it may constitute a violation of international law, constitutional rights, and basic principles of justice.

The Broader implications: Statelessness, human rights, and the erosion of due process

Together, these developments expose a deeply troubling pattern in India’s approach to foreigners and refugees in Assam, especially Rohingya and Bengali-speaking Muslims:

- The conflation of statelessness with criminality leads to indefinite detention and mass pushbacks that violate fundamental human rights and international legal standards.

- The Foreigners Tribunals in Assam, widely criticised for lack of due process, continue to declare hundreds of individuals foreigners—many wrongfully—subjecting them to detention and the risk of forcible removal.

- Deportations executed without diplomatic agreements or proper notifications amount to illegal “pushbacks”, shifting responsibility onto neighbouring countries ill-equipped to absorb such persons.

- The opacity and lack of accountability in these processes undermines public trust, violates constitutional guarantees of liberty, and renders invisible the suffering of those caught in legal limbo.

- The Government’s eagerness to “empty” Matia detention centre is a hollow metric if it rests on forced expulsion rather than lawful deportation or rehabilitation.

- The persistence of cases like Oladimeji’s reflects systemic failures to honour judicial mandates, international obligations, and the rights of detainees.

As Assam’s Matia detention centre becomes a symbol of secrecy, cruelty, and administrative impunity, the urgent need for transparency and judicial oversight cannot be overstated. The stories emerging from behind its high walls—of coerced deportations, prolonged illegal detentions, and disregard for basic human rights—reveal a deeper rot in India’s treatment of migrants and refugees. Upholding the Constitution means more than rhetoric; it requires an unwavering commitment to legal due process, dignity, and non-discrimination. Civil society, courts, and the media must refuse to look away. What is at stake is not just the fate of a few individuals, but the very soul of a democracy that claims to abide by the rule of law. Ultimately, the crisis at Matia detention centre is not merely an administrative issue. It is emblematic of a broader crisis of justice, humanity, and the rule of law—where the most vulnerable populations become collateral damage in nationalist and securitisation agendas.

Courtesy: Sabrang India

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.