Conundrum of Dharavi Redevelopment: A Case of Systematic Displacement of Workers From Mumbai

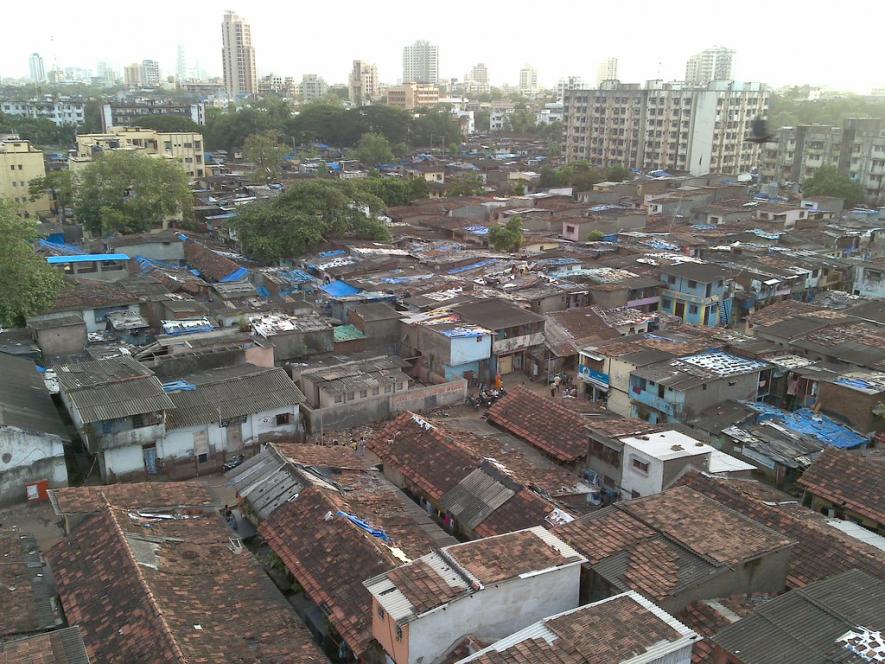

Dharavi slum in Mumbai. Image Courtesy: Flickr

The redevelopment of Dharavi has been in waiting for close to two decades. Dharavi Development Plan (DDP) announcements in the past have been closely related to elections. It has again made it to the headlines because of the impending municipal elections in Mumbai and the Parliamentary election in 2024. The earlier BJP-Sena government had floated a revised DDP in 2018 that the Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) government cancelled.

Now again, after the political drama in Maharashtra, the BJP-Shinde Shiv Sena government has announced the project and issued a related government resolution dated September 28, 2022. With no well-defined program, the current government will bank heavily on the success of the much-delayed Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP) and other such infrastructure projects in the state to attract voters.

With a working-class population - Dharavi had never been BJP or Sena stronghold. About 30% of the Dharavi population is Muslim, 6% Christian, and the rest are Hindus. The Hindus comprise largely dalits engaged in caste-based occupations like tanneries and leather, pottery, and recycling.

Dharavi hosts a million-plus population comprising leather goods manufacturers, recyclers, potters, garment manufacturers, and many other small manufacturing units, along with a huge slum population that works outside Dharavi. The land is a mix of government land and private land owners plus a Koliwada.

There is a diversity of residency in slum and non-slum areas, including land and tenement ownership. The commercial activities and residencies within are also complex. The redevelopment plan seems to treat increased FSI as a magic wand solution for density, slum redevelopment, creation of amenities and infrastructure for the open market. Delay in starting the project has created sharp divisions between the owners, slum dwellers, and commercial and manufacturing units.

At one end of the spectrum are the slum dwellers who have been waiting for close to two decades for their dream home in the city of dreams, and to the other end are landowners who do not want to be a part of the slum redevelopment and are seeking self-development for the last few years. Field experiences (author's earlier engagements with the commercial and manufacturing units) point movement of commercial and manufacturing units to the peripheries of the MMR region. Therefore, it is meaningless to oppose the plan in totality at this juncture. At the same time, the announcement of rehabilitation of non-eligible tenements (tenements with no documentary evidence, the tenements on uppers stories, the rented) would be rehabilitated on the salt plan land at Wadala is something to look up to.

Therefore, It is important to engage with the plan to make the project inclusive for the most vulnerable and policy disenfranchised.

There are numerous reasons to believe the DRP will be implemented this time.

One, the strategic location of Dharavi with connectivity to the central, harbour, and western lines and its proximity to Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC) makes it an ideal location for redevelopment at this juncture. BKC has become an unmanageable monster, with the commercial zone almost full and the residential zones outpricing the very rich. BKC was a green field project on 370 acres of low-lying area without development constraints. Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) was appointed the planning authority in 1977 – it planned 370 hectares of land in a zoned manner from A to I zones. Of the total land area, nearly 40% was identified for commercial purposes, followed by 37% for social and 23% for residential purposes.

Subsequently, it made a detailed plan to develop zone G as International Financial Business Centre in 1998. Since 2001 till now the whole gamut of service-sector multinationals, as well as foreign consulates, the National Stock exchange, and Bharat Diamond Bourse (exchange), have relocated to BKC, providing approximately 2 lakh jobs. It's also a go-to destination known for its high-end restaurants.

In addition, Reliance Jio World Drive Mall and Reliance Jio Convention Centre were inaugurated last year and this year, respectively (RIL opened India's largest convention Centre at Jio World Centre with a 5G network). BKC has positioned itself as one of the key nodes in the global economic network. However, it may be unmanageable and hollow, needing complementary infrastructure. The government views BKC as a cash cow and has kept the prices in this region high to maximise its revenues. But this also acts as a deterrent to private developers who may find it financially unviable to buy land and build projects here.

The residential developments have not taken up as expected, and the uptake of social amenities has also been slower than expected. Recently, the auction of plot no C65 (initially residential) but opened for commercial activity had no takers. Also, the earlier auction was held for leasing out three plots, C44, C48, and C68. They were later clubbed and found no bidders, indicating that it outpriced even the multinationals.

In the coming years, metro connectivity will be developed between the various business districts in the MMR region, which will once again make it a sought-out area for investment. Given the case, BKC will hold on to the current prices while needing infrastructure around BKC to complement it; Dharavi, therefore, becomes an ideal location for redevelopment at this point. Putting it in simpler words - to encourage investment in BKC, the neighbouring areas need to be developed to match the standards. This can be done by freeing land in Dharavi. Dharavi redevelopment will aspire to do the same while displacing the life and livelihoods of the current residents of Dharavi.

Two, the wait for eligible slum dwellers has been too long for ownership housing in the city of dreams. At one level, there is impatience amongst slum residents, and on the other hand, there is pressure on the government to allow the self-development of landowners in Dharavi. The government will not allow self-development as it will lose the prime land that will bring them long-term revenue. The eligible slum dwellers will not show much opposition as many of their demands has been met. The demand for a larger carpet area, a higher amount for corpus fund, an extended cutoff date, and the purchase of additional space at cost from the developer have found space in the 2018 GR and the latest one.

For commercial tenements – an area of 225 sq ft will be made available the rest can be bought at cost; hazardous industries will not find space in the project, build-up area (BUA) for potters' business activity will be 225 sq ft and residential area of 225 sq ft will be free and additional space can be bought at cost. Back-to-Back commercial tenements will be allowed after exhausting all the available space. The first floor will also be allocated for commercial purposes for the potters. Dharavi has multiple layers of complexities – with slum dwellers (owners), slum dwellers (rented), landowners, non-slum residents, and original residents.

In comparison, slum dwellers seem to have gotten a better deal than others. Commercial and manufacturing establishments have gotten a raw deal under Dharavi Redevelopment. This cluster currently houses 20,000 small-scale work units of leather export, textile and zari work, glass, pottery, and recycling, contributing to Dharavi's one-billion-dollar economy.

Three, government (SPV) is likely to earn huge revenues due to redevelopment as the principal investor. Apart from that, the economic activities that will start post-redevelopment shall be a source of regular income for the government from property tax and other taxation from commercial activities. In the last two decades, the cost overruns for the project have increased six folds– the cost estimates for the project went up 6.5 times from Rs 4,000 crore in 2004 to Rs 26,000 crore in 2019, and now the estimated cost is Rs 28,000 crore. Some estimates of the profits to be earned by railways in exchange for 45 acres of land is close to Rs 1,100 crore, a minuscule 0.2 % of the profit.

Four, the investors have been provided with many concessions in forms that are unimaginable - premiums paid by the developers, inspection charges, and goods and service tax have been exempted. This is a carrot that will attract investors. The latest news is that 11 companies have shown interest in the pre-bid meeting and tendering process, and the deadline for the tender has been extended by 15 days.

Recently, a BJP minister claimed that at least three companies that have shown interest would qualify for the project.

WHAT IS IN IT FOR THE WORKERS?

Dharavi is home to a million-plus population of which many will lose their livelihood and habitat. As for eligibility, the ground floor tenement resident must prove the tenement's existence before 2000. The ones rented or owned on upper stories shall be ineligible, as is the case for all slum redevelopment. And an FSI of 5 (including the fungible FSI). Such high FSI coupled with high densities of Dharavi will result in the high-rise, high-density buildings that will be unsustainable to maintain for the workers of Dharavi. Over the years, many will find it difficult to maintain and either rent or sell the tenement, thereby getting systematically displaced from the city centre.

Also, this high-rise, high-density redevelopment is a hotbed for infectious diseases. A study commissioned by MMRDA's Environment Improvement Society reveals that every 10th person suffers from TB in Govandi. MMRDA study carried out by Doctors For You in 4080 households in three low-income resettlement colonies in Govandi and Mankhurd is suggestive of sub-human living conditions in the guise of rehabilitation.

Poorly ventilated homes with little air circulation are breeding grounds for disease (1 in 10 living in slum rehab colonies has TB, and lack of air and light is seen as the cause). Dharavi rehabilitation should not follow the mantra of high FSI coupled with high density. The development control norms should be followed without any exemption on the project's viability.

At the same time, the most vulnerable, of whom there are no talks, the ineligible, and the ones on rent will be finding space in rented accommodation at Wadala Salt pan land. This is a classic case of the dilemma of development – as one of the most vulnerable in the housing spectrum- the rented and ineligible shall find a home but on land that has acted as sponges for Mumbai. Adequate open spaces should be created in any such development so that some part of the land continues to act as sponges to avoid flooding.

DRP has brought into focus the need for rental housing in the cities. The need for rental housing has been a neglected area in housing discourse, and it is only in the last couple of decades that policy documents have talked about rental housing. Alas, all that has remained on paper. It took a pandemic like COVID to announce the much-needed rental housing scheme in the form of relief measures for migrant workers. DRP allows the city to develop rental housing for the most vulnerable.

In conclusion, the entire premise of the DRP throws light on various things. It is the first time in the history of the DRP that there are talks about rehabilitating the ones not eligible for affordable rental housing. However, there are many grey areas concerning maintenance, rent, amenities, the annual increment, protections from evictions, etc. Civil society organisations working with informal workers should raise these questions.

Additionally, the high-density, high-rise development has not worked as an ideal form of rehabilitation. A rethought of the typology and location of rehabilitation needs a fresh relooking. This relooking should not be from the filter of the project's viability but to provide dignified housing and livelihood to the workers.

Moreover, A developmental monster like BKC needs complementary infrastructure around it to sustain itself. This is also indicative of the shift from all forms of manufacturing to service. A ripple effect of this kind of development shall create a city that houses a particular class, not workers. In this process, millions of toilers will lose their livelihood and habitat. Can we afford that? We need to think about whether service cities are sustainable in the Indian context or whether we need a mix of service and manufacturing cities.

The writer is a part of the Habitat and Livelihood Welfare Association & Working People’s Coalition. All views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.