Can Judiciary Ignore its Responsibility?

Judiciary logo. Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

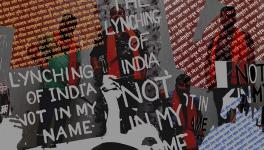

Indian society is going through a massive shift towards monolithic majoritarianism. It is increasingly autocratic, illiberal and regressive, fostering undignified conditions for the religious minorities. Deeply polarised along religious lines, India is turning antithetical to its foundational values. First law minister and Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution, BR Ambedkar, had imagined a secular Constitution that embodies Mahatma Gandhi’s principle of non-violence and Rabindranath Tagore’s vision of universalism. The Constitution promised that every community—more so the minorities—would not be questioned for their food preferences, marriage and kinship practices, clothing choices, prayer and congregation norms.

However, Indian minorities face rejection, intimidation and humiliation daily; even their citizenship rights are regularly challenged. It is like having forgotten that any community finds its time-tested preferences intrinsically valuable and cherished. Even in an age of hyper-globalisation, with information, art and culture and consumer products in free flow—not to mention cross-border migration—it is difficult to imagine any community as bereft of uniqueness. In fact, even those who oppose other communities seek to conserve their own way of life and essence.

Not that life preferences are eternally fixed, or we should not contest or reform them. While contestation is essential for enlightened social change and ideas, ill-intentioned majoritarianism is unwelcome. When explicit political interests back the latter, it fosters cultural-economic intimidation and psychological humiliation. In such a situation, we must remember the significance of “epistemic responsibility”. The Indian judiciary is vested with superior epistemic conditions. In other words, its memory, imagination, perception, reasoning, understanding, and wisdom far outweigh an ordinary citizen with the same capacities. What is happening in India requires the judiciary, as the protector of the Constitution, to act.

The Constitution protects fundamental rights, and the State is duty-bound under the Directive Principles of State Policy to secure these. Marc Galanter, an eminent scholar in the sociology of law, who wrote the well-regarded 1998 book, Hinduism, Secularism and the Indian Judiciary, has observed that the “penal law in India is extraordinary solicitous of religious sensibilities and undertakes to protect them from offence. The electoral law attempts to abolish religious appeals in campaigning”.

Further, it is common knowledge in India that secularism protects the time-tested ways of life of every community. It encompasses the spontaneous engagement of people with literature, art, cultural practices, education, sporting activities, economic exchanges, social interactions, political participation, friendship, trust and fraternity. Obviously, the judiciary is aware that the citizenry knows what its fundamental rights are, along with the State’s duties and the responsibilities of the judiciary. However, the capacity and authority that vest with the judiciary to reinforce constitutional values are not proportionate. This capability is a privilege of the members of the judiciary, which the majority of ordinary citizens (and State counterparts) cannot match. As constitutional authorities, courts are in a more responsible position for protecting fundamental rights.

There is every possibility of self-interest-driven majoritarian communities or State power seeking to pursue their own benefit by compromising fundamental rights and disregarding the Directive Principles. The judiciary, however, cannot overlook the consequences of such compromises. And there is an implicit reason for the citizenry reposing trust in the judiciary. It is because it can make judgments with a view to the future, something well beyond the capacity of those who seek justice from courts of law. This trust must not be taken for granted. Instead, it is contingent upon the courts to fulfil their constitutional responsibility and validate its guarantees through their judgments.

The judiciary can claim the continued trust of citizens when all members of society, minority communities included, feel hopeful when they approach seeking rulings. It also continues through people’s willingness to comply with verdicts, even when the odds are against them. However, if a sense spreads that rights such as citizenship, or to profess a profession, choosing one’s food, clothing, or practising a personal law are being compromised, this trust begins to withdraw. Given the privileges of constitutional authorities—their epistemic superiority—and the moral power of the Indian judiciary, it would indicate shrinking confidence. This is especially true of the Muslims, whose battering is taking place under the gaze of every citizen.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights has indirectly hinted at the role of the judiciary in ensuring rule of law and upholding justice for minorities, when it directly alerted the government of its failures to do so. It should be taken seriously. Trust must be earned as much as it is granted.

The author teaches economics at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Hyderabad, India. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.