The Birds That Don’t Frighten

Fifty years ago, on October 2, 1968, Mexican students protested against their government for a new future. They were brutally attacked. It was the bloodiest moment in the student uprisings of 1968. It marked Mexico. It continues to mark Mexico.

The Olympics

On October 18, 1963, Mexico won the bid to host the 1968 Olympics. With the backing of the Soviet Union, Mexico City outbid its Northern competitors, Detroit (USA) and Lyon (France). For the first time, the Olympics would be held in the Third World.

Since the Second World War, Mexico had been undergoing extensive industrial growth, rapid urbanisation, and development of domestic production and consumption. The government, led by President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, was eager to broadcast to the world the economic progress of the so-called “Mexican Miracle”, and claim its place as a modern democratic nation. However, the economic boom was barely felt by most of the country’s poor—the public spending of $150 million on the Olympic games was an affront to many—and the government was authoritarian at best. Since the 1920s, a single political party—Partido Revolucionario Instituticional (PRI)—had been in power, which had virtually eliminated all political opposition.

During the mid-1960s, as part of a global wave of student uprisings, a popular unrest among Mexico’s students, workers, and peasants was growing. This unrest would consolidate into a powerful force over the summer of 1968, in the lead up to the Olympic games. The government, however, was not going to let anything happen to ruin their moment and would use all bloody tactics at their disposal to preserve their “Games of Peace.”

Todo Es Posible en la Paz (Everything is Possible in Peace)

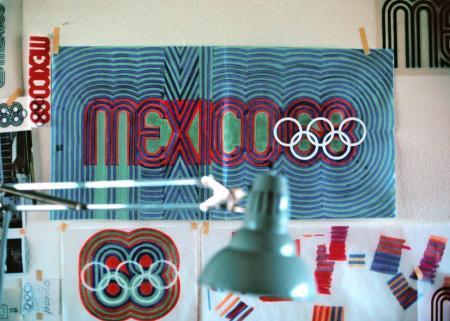

In November 1966, Lance Wyman, a 29 year-old graphic designer from New Jersey, set off to Mexico City on a one-way ticket. He was accompanied by his wife, Neila, and collaborator, Peter Murdoch to participate in the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) design competition. The brief was open: Create an identity with the Olympic’s five-ring logo, and incorporate the host country’s language, Spanish (and French and English) into all the signs and publications. They had two weeks to present a design. Never having visited Mexico before, they spent those days studying Aztec sun stones, Mayan murals, Toltec warrior statues, and Hiuchol (or Wixáritari, meaning “the people”) textile yarn paintings.

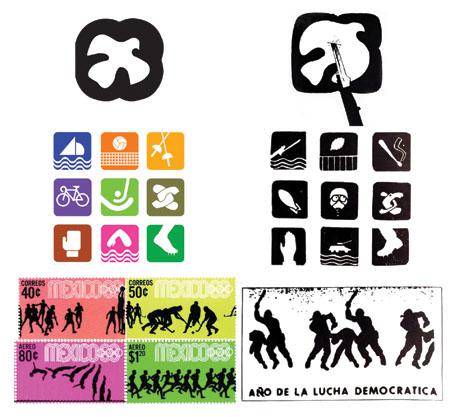

Their winning design incorporated the bright colours, geometries, and bold lines of Mexican indigenous imagery with the Op Art (an abstract artform using visual illusions) that was popular in New York City’s contemporary art scene at the time. The logotype cleverly used the rings of the Olympic logo to construct the numbers “68”, the year of the Olympics. The logo was accompanied by a custom-designed typeface of bold, pulsing lines. The radiating lines signalled movement, dynamism, and mass communication—with this logo, Mexico would broadcast itself to the world. For the next 18 months, the organising committee, led by architect Pedro Ramírez Vásquez, worked with the young designers from New York to produce the image of modern Mexico through memorabilia, uniforms, stamps, stadiums, public signage, maps, wayfinding icons, and publications, to name a few. They were guided by the campaign slogan, Todo Es Posible en la Paz (Everything is Possible in Peace).

The convergence of the three cultures in the designs—pre-Colombian, Spanish colonial, and the modern independent nation—captured the vision of social harmony the country wanted to project. However, it would be in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas (Three Cultures Square) in Tlatelolco where the student massacre would take place, ten days before the games started.

¡No queremos olimpiadas, queremos revolución! (We don’t want the Olympics, we want revolution!)

The student movement began consolidating in July 1968, after a mobilisation in support of Cuban Revolution was met with violent police repression and mass arrests. By this time, student groups in various universities had been mobilizing, driven by students at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM)—the country’s largest publicly funded university. The National Strike Council (CNH) was struck with representatives from all the universities, who were elected in a general assembly, and would be the main organisational body of the student movement. They demanded an end to police repression, respect for student organisation, abolition of granaderos (the tactical police force), freedom of political prisoners, dismissal of the chief of police and his deputy, and the identification of officials responsible for the government bloodshed.

Student brigades organised in full force. Engineering students designed balloons to shower leaflets. Theatre students led street performances. As the government repression grew, so did popular support for the student movement. The general anti-government sentiment unified the struggles of workers, peasants, women, and students. The demonstrations denouncing police repression and government corruption, and calls for democracy, began to swell. Central to the mobilisations were the Propaganda Brigades that were responsible for the graphic production—flyers, posters, banners, and stickers—to build up moral and material support for the movement. These graphics provided the testimony for the movement, countering the misinformation of mass media. They exposed government lies, denounced state violence, popularised the movement’s demands, and called people out to the streets.

This work was led by the brigades of the National School of Visual Arts at UNAM and supported by the National School of Painting and Sculpture and small improvised workshops set up in different schools. There already existed a rich tradition of revolutionary art and artists in Mexico, most notably the “Mexican School” of artists like Diego Rivera and later the Taller de Gráfica Popualr (People’s Graphics Workshop) of young printmakers dedicated to the Mexican Revolution. But by the mid-1960s, a new generation of visual artists in these schools were searching for new forms of expression, technical experimentation, and forms of collective and individual work. The Propaganda Brigade was one of those living laboratories.

The CNH provided direction and came to the brigades for graphic support. They used inexpensive and quick methods: Linoleum engravings, silkscreen printing, and hand cut stencils. Their messaging was didactic, direct, and popular. Every street, bus, school, and public space became a canvas in this visual battle of ideas. They recycled, modified, copied imagery and called it “cultural parallelism.” The bayonet, gorilla police officer, and bloody dove became the counter symbols of the official imagery of peace, patriotism, and the Olympics. Wyman’s designs became fodder for student co-optation: Sporting event icons were replaced with grenades, boots, bombs, and gas masks; the ’68 logo was superimposed with tanks and police in riot gear; and “Peace dove” images lining the streets were sprayed blood-red.

As the Olympics drew closer, the government repression grew. It became increasingly difficult to post images, yet the brigades found new methods to put up their work—one technique was to use wet rags or saliva to paste posters on moving cars and buses. But the movement continued to grow, culminating in the August 27th protest in Zocalo, where half a million people came to challenge the government. It remains one of the largest mobilisations in Mexican history. On September 1st, President Díaz Ordaz announced that the government would no longer negotiate with students—all protests would be met with police confrontation.

In the days that followed, students mobilised for a peaceful “Silent March”. This moment marked one of the most important experiments in collective production, where the old San Carlos Academy building was turned into a great workshop. Students, professors, activists, printmakers, and administrative workers tirelessly worked around the clock to produce the materials in preparation for the march. Over the course of those months, the Propaganda brigades, led by the National School of Visual Arts, was a living organism in which artists and designers, trained and untrained, assumed their social responsibility and took up their posts in the ideological battle.

Misión cumplida. Tlatelolco 2 de Oct. (Mission accomplished. Tlatelolco, Oct 2)

Late in the afternoon on October 2 students began to assemble in the Three Cultures Square of the Tlatelolco neighbourhood of Mexico City. The plaza was designed by Mexican architect and urbanist Mario Pani, and it had been completed in 1966. Similar to the vision of Olympic committee’s visual identity for the ’68 games, the square pays homage to the three periods of Mexican history—pre-Columbian, Spanish colonial, and post-independence.

As the sun began to set, the police, army, and tanks began to surround the crowd, trapping the thousands of students who were peacefully gathered. It was ten days before the games, and the government would make sure those games would continue, unencumbered. A shot was fired from a nearby building—the government’s claim that the protesters fired the first shot was later disproven. This pretext unleashed a bloodbath by the police and army. Over the next two hours, 15,000 rounds were fired. Protesters were indiscriminately arrested, whether they were injured or not.

The official death toll was four people, but most sources report a number in the hundreds, some up to thousands. The government attempted to buy the silence of parents whose children were murdered. They tried to pretend the massacre never happened. Until today, the death toll remains controversial.

The repression worked. The protests stopped. The government had its Olympic games. The Tlatelolco Massacre became buried behind the headlines, and today is mostly forgotten outside of Mexico.

Pues prosiguió el banquete. (As the banquet continued)

What is now known is that the protesters did not shoot first, and likely the shooter had been working with the government. What is also known is that the CIA sent Winston Scott, as the Mexico City station chief from 1956-1969 (or “virtual proconsul”, the power behind the throne). One of his tasks was to suppress the student uprisings while payrolling three consecutive Mexican Presidents.

There has still never been a truth commission investigating the massacre, and the violent repression against social movements continued in the “Dirty War” policies in the decades since, in which hundreds of people were disappeared or murdered in extrajudicial killings. Then Secretary of the Interior, Luis Echeverría, who became Mexico’s President was charged with genocide for being the mastermind behind the Tlatelolco and Corpus Christi (1971) massacres. Though those charges were dropped in 2006, the Committee 68—an organization that continues to fight for justice for the Tlatelolco Massacre—appealed last month to reopen the case against Echeverría. Last week, the first government institution, a subsidiary of the Department of the Interior, recognised that the Tlatelolco Massacre was a state crime.

In July of this year, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) won a landslide victory in the Presidential elections. In the wake of the 50th anniversary of the Tlatelolco Massacre, the left-leaning former mayor of Mexico City has vowed to never use military force against civilians while promising universal access to university. He will be sworn in as President on December 1st, and what will become of these hopeful promises remains to be seen. The student movement never quite reconsolidated, nor did the solidarity work between the artists and social movements. Yet moments of mass student mobilizing have continued in the face continued government repression, from #YoSoy132 movement of 2012 to national outrage in response to the 2014 kidnapping and disappearance of 43 students in Ayotizinapa (who were traveling to a Tlatelolco Massacre commemoration event).

Every year students gather at the Three Cultures Square to re-enact the Tlatelolco Massacre. They will not let this story be forgotten. Half a century later, this story of a movement in which students, workers, and peasants united, whose voices were amplified and popularized by the proliferous art spread on every street, remains an important inspiration.

¡Que vivan los estudiantes,

jardín de las alegrías!

Son aves que no se asustan

de animal ni policía,

y no le asustan las balas

ni el ladrar de la jauría.

Long live the students,

gardens of joy!

They are birds that don’t frighten

because of animals nor police,

not scared of bullets

nor packs of barking dogs.

—Violeta Parra, Me Gustan Los Estudiantes (I like the students, a hymn of the ’68 student movement)

Tings Chak is the Designer of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research (thetricontinental.org).

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.