Bihar: Saga of Two Decades of Labour Migration, Unemployment

File Image

For decades, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Jharkhand have functioned as India’s great labour reservoirs—feeding the industrial and urban expansion of more developed regions while languishing in economic stagnation themselves. Nowhere is this paradox more visible than in Bihar, where structural neglect and political inertia have produced one of the largest migration streams in the Global South. As the state marks two decades of rising outmigration, the imperative for a transformative, self-driven renewal has never been more urgent.

From the snow-clad frontiers of Leh–Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Haryana, and Delhi to the mist-laden hills of Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Nagaland, Meghalaya, Manipur, Assam, West Bengal, and Odisha in the North, and further down to the industrious Southern and Western states of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, and Maharashtra—the nation’s silent backbone of the working class has long been constituted by the tireless labourers from Bihar.

Read also: India’s R&D Crisis Through the Lens of Bihar

For decades, Bihar has served as the reservoir of manpower that fuels India’s engines of growth—powering metropolitan hubs such as Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai, Kolkata, and Hyderabad, as well as the vast industrial corridors spanning Gujarat, Maharashtra, Delhi, Panjab, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu.

This vast migration of labour is not a narrative of opportunity, but one of systematic extraction—a movement compelled by survival rather than aspiration. Millions of workers, uprooted from their agrarian homes, are forced to inhabit the most squalid urban margins (slums), where even the most basic human needs remain unmet. Their journey reflects a deeply entrenched and deliberate unevenness within India’s developmental trajectory—one in which capital accumulates in metropolitan centres while the countryside is drained of its youth and vitality.

Decades of policies oriented toward urban capital, metropolitan infrastructure, and corporate incentives have ensured that prosperity remains geographically concentrated, while poverty and precarity are continuously reproduced in the peripheries. The consequence is a nation that flourishes on the toil of those who are systematically denied the means to flourish within it.

Bihar: From Civilisation’s Core to Capital’s Periphery

Among these heartlands, Bihar stands at the crossroads of history and contradiction. Once the intellectual epicentre of India—home to the ancient universities of Nalanda and Vikramshila, and the republican traditions of Vaishali—Bihar today bears the deep imprints of economic neglect and political marginalisation. Its youth migrate not out of aspiration but out of necessity. Migration, once viewed as a symbol of social mobility, has now become a ritual of survival—a forced exodus from a homeland that can no longer sustain its own people.

The collapse of traditional industries—such as sugarcane, jute, rice, flour, pulse, oil, and paper mills—coupled with the stagnation in the establishment of new universities, engineering and medical colleges, and schools, has crippled the state’s capacity to generate employment.

Consequently, the much-proclaimed “double-engine government” of the Bharatiya Janata Party–Janata Dal (United) alliance has failed to create meaningful opportunities for either the skilled or the unskilled labour force, leaving the majority of the workforce excluded from productive participation in developmental and economic activities.

This, however, is not the failure of Biharis; it is the failure of India’s capitalist framework. For decades, Bihar’s economy has been structured not to empower its people, but to serve capital elsewhere—to supply a steady stream of cheap labour from its agrarian villages to the metropolitan and urban construction sectors, transport networks, ports, small-scale industries, and domestic labour markets across the subcontinent and beyond.

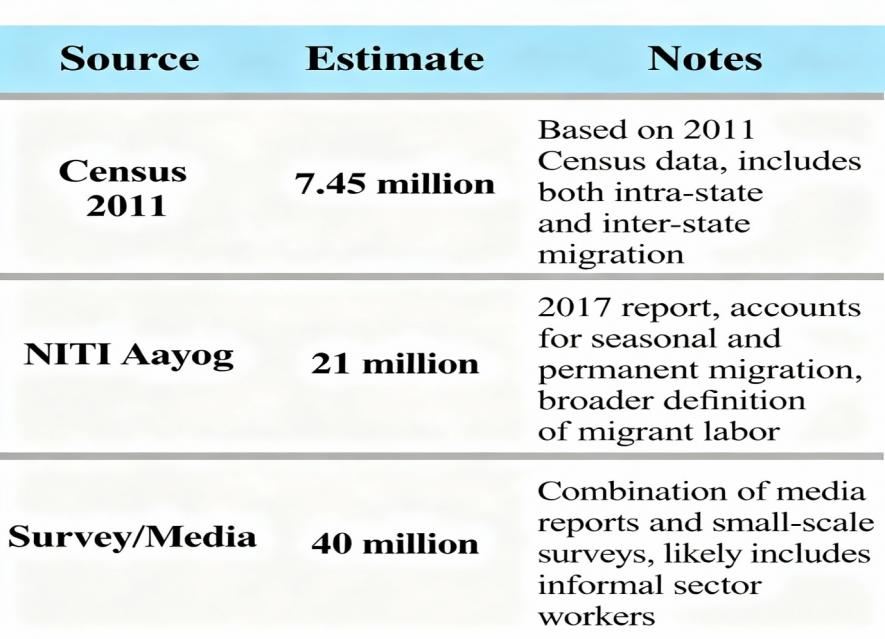

The Exodus and Its Numbers

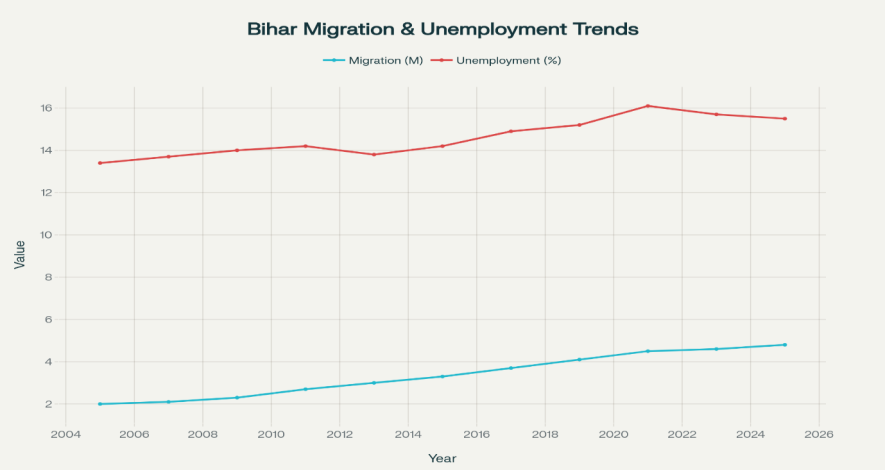

Between 2005 and 2025, Bihar’s outmigration has more than doubled—from approximately 20 million to nearly 50 million people. Across the state, countless villages stand bereft of their youth, emptied by the relentless tide of migration to other states. Beneath these statistics lies a stark reality: the collapse of local employment and the commodification of human labour.

The process of industrialisation in Bihar remains an unfinished project, stalled by the entrenched dominance of feudal–capitalist forces that continue to control both the economic and political apparatus of the state. These forces have perpetuated the creation of a vast reserve army of unemployed youth, consistently hovering around 42 to 45%, while per capita income languishes at less than half the national average. Bihar’s poverty rate of 33.7% and its industrial growth of barely 2% narrate the same story—a region abandoned not by accident, but by deliberate design.

Female Labour Force Participation: A Subtext

Bihar’s female labour force participation (FLFP) encapsulates a nuanced interplay of entrenched socio-cultural norms, economic imperatives, and evolving policy interventions. Historically, women’s engagement in the workforce has remained significantly below the national average—oscillating between 8–10% during 2004–2012, in contrast to India’s 20–25%. This disparity can be attributed to pervasive patriarchal constraints, limited access to quality employment, and increasing educational enrolment among women.

Since 2017–18, data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) reveals a modest yet discernible upward trajectory, particularly in rural Bihar. Initiatives such as self-help groups (SHGs) and community-based livelihood programmes like Jeevika have expanded women’s economic participation by fostering collective entrepreneurship and local employment opportunities. By 2023–24, Bihar’s FLFP had surpassed 14%, signifying incremental progress while still lagging behind national benchmarks.

Migration dynamics, however, remain profoundly gendered. As per the Census 2011, approximately 86% of female migration is marriage-driven, with a mere 1% motivated by employment—compared with14% among men. Yet, with escalating male outmigration, a subtle reconfiguration is emerging: women are increasingly assuming economically active roles within agriculture and the informal sector, often managing households single-handedly in the absence of male members. Despite this shift, pervasive issues—such as low remuneration, job precarity, and systemic gender discrimination—continue to circumscribe the emancipatory potential of women’s labour participation in Bihar.

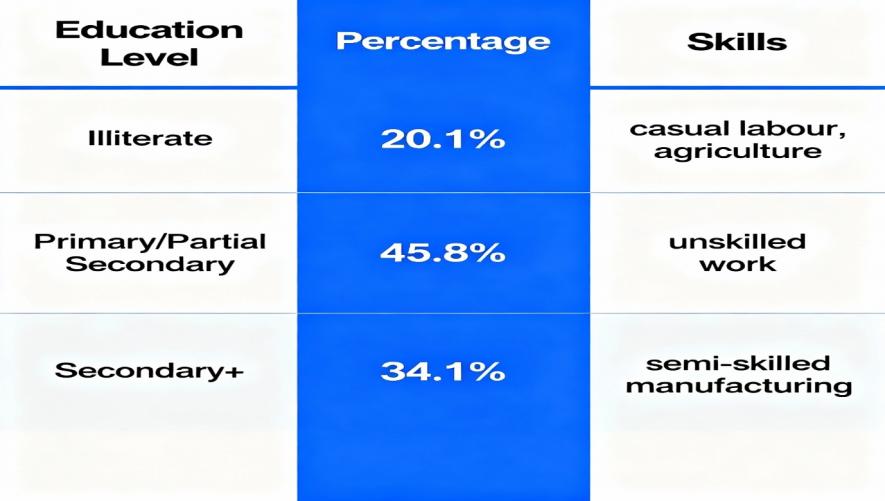

Education & Skills Profile of Migrated Labour

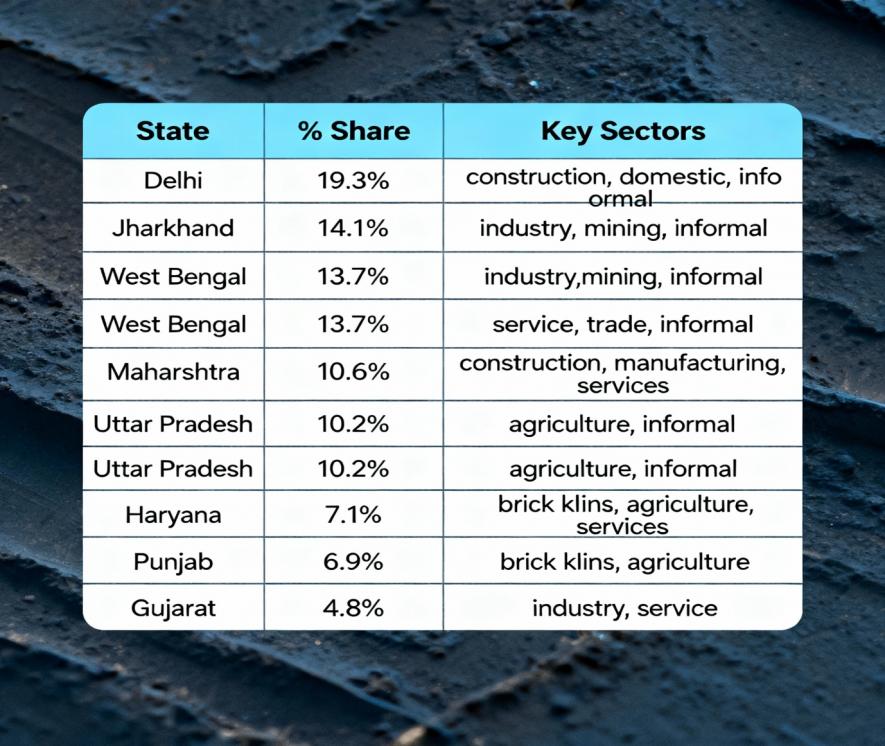

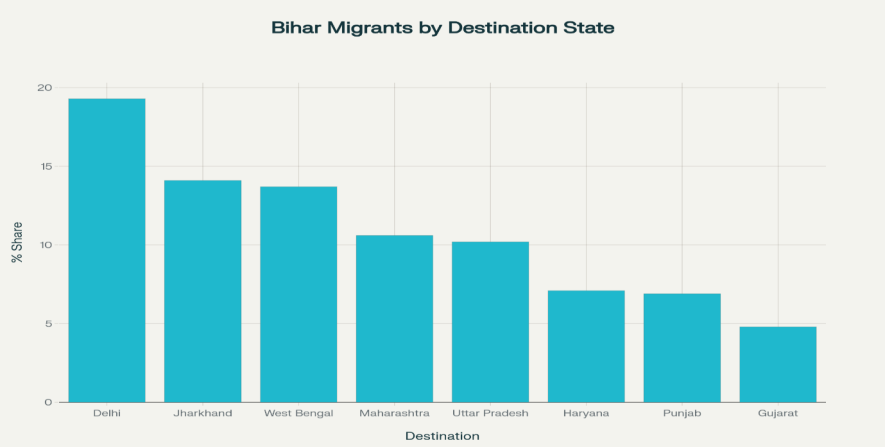

Chart: Distribution of Migrants from Bihar by Destination State

Distribution of Migrants from Bihar by Major Destination State (Source: Geography of Migration in Bihar; 2025).

Drivers of Migration

-

Landlessness and agrarian stagnation: Small or fragmented holdings limit income and absorption of the rural workforce.

-

Limited local employment: Industrial and non-farm sectors remain underdeveloped.

-

Caste/social marginality: Scheduled Castes, Tribes, and OBCs are over-represented in migration and face greater precarity (Source: Out-migration from Bihar: Major Reasons and Destinations, 2019)

-

Historical social networks and family connections: Migration corridors link specific districts in Bihar to certain urban centres.

Living and Working Conditions

At the destinations, migrants confront multiple layers of vulnerability — ranging from exploitative informal employment arrangements and exclusion from social security schemes to cultural and linguistic alienation within urban settings. The lack of institutional mechanisms to safeguard migrant welfare deepens their socio-economic precarity, even as their labour remains indispensable to the host states’ economic vitality.

Labour Without a Homeland

Bihar’s workers are everywhere yet belong nowhere. They build skyscrapers in Mumbai, lay highways in Haryana, stitch garments in Punjab and Gujarat, and serve in hotels from Kerala to Malaysia, Singapore, Canada, the US, and the Gulf countries. Their sweat sustains the comforts of India’s middle class and the profits of its corporate elite.

Yet, for all their labour, they remain invisible in the story of national progress. Their remittances keep families alive, but they cannot build futures back home. This is the cruel paradox of India’s growth: prosperity built on displacement, and development achieved through the denial of dignity.

Bihar’s economy now depends on remittances, creating a strange illusion of prosperity—money without production, consumption without creation. This is not development; it is dependency, a mirror image of global capitalism where the periphery feeds the centre.

The Political Betrayal

Bihar’s condition is not simply economic—it is deeply political. For decades, successive governments have treated the state’s poverty as a political resource, not a challenge to overcome. Populist schemes have replaced long-term investment; slogans have replaced structural reform.

Agriculture stagnates, industry falters, education remains underfunded, and governance is hollowed out by corruption and patronage. Behind every promise of “development” lies a refusal to question who controls production, land, and capital.

This is why Bihar’s crisis persists: because the structures of power benefit from its weakness. The bourgeois state—whether led by Delhi or Patna—depends on a cheap, mobile workforce. It cannot afford Bihar to stand on its own feet; its economy must remain a labour supplier, not a competitor.

Women and the Silent Revolution

Amid this crisis, a quieter transformation is underway. As men migrate, women are stepping into new roles—cultivating land, managing households, and joining self-help groups like Jeevika. The FLFP rate in Bihar has risen from 8–10% in the early 2000s to around 14% today.

But this is not emancipation—it is a burden without recognition. Women work longer, earn less, and face greater insecurity. Their labour keeps the village economy alive, yet it remains undervalued and unpaid. The migration of men has exposed both the strength and the subjugation of women in a patriarchal economy that still refuses to see them as equals.

The Moral Question of Development

Bihar’s story forces India to confront a moral question: Can a nation call itself developed when its foundation is built on the exile of its workers? Can “inclusive growth” mean anything if entire regions are condemned to remain labour colonies for the comfort of others?

The truth is stark: India’s economic success is built on internal colonialism—the systematic transfer of labour, value, and human potential from poor states to rich ones. Bihar’s poverty is not an accident of geography but a consequence of power.

Toward a Politics of Renewal

The struggle for Bihar’s renewal must therefore go beyond technocratic reforms or welfare packages. It must challenge the relations of power that keep the state subservient to capital. Real transformation will come only when labour ceases to be a commodity and becomes the foundation of dignity, ownership, and control.

Bihar does not need pity; it needs power—the power of collective organisation, industrialisation rooted in justice, and political consciousness that refuses dependency. Its people have built India; now, they must be empowered to rebuild Bihar.

Only then can the promise of democracy and development find its true meaning—not as a privilege for the few, but as the collective right of those who made the nation with their hands.

The Road to Renewal

Bihar’s transformation demands not sympathy, but deliberate, visionary, and sustained action. The state must pivot from dependence to self-determination, from exporting labour to cultivating livelihoods. Investment in industrial corridors, skill enhancement, agricultural modernisation, and entrepreneurship must supplant the short-term populism that has long defined its political culture.

Such transformation cannot be engineered from without; it must be conceived, claimed, and carried forward by the people of Bihar themselves. A new social compact—rooted in education, equity, and empowerment—holds the power to restore dignity to the very youth whose toil has shaped India’s cities, but remain estranged from the prosperity they helped construct.

A Final Reckoning

The question is no longer whether Bihar can rise—it can, and indeed, it must. The true measure of this moment lies in whether its leadership can summon the political resolve, moral fortitude, and strategic imagination required to orchestrate such a renaissance.

If not now, then when?

And if not for Bihar’s youth—the rightful inheritors of its history, its labour, and its hope—then for whom?

Bihar stands at a historic inflection point—endowed with one of India’s youngest populations, a strategic geography, and an indomitable work ethic. What it lacks is neither ability nor aspiration, but a governance architecture bold enough to convert potential into progress.

The path forward requires nothing short of a new political grammar—one that privileges production over populism, inclusion over inertia, and vision over vote banks.

Policy Recommendations

-

Distribute 2.2 million acres of land (acquired under the Ceiling Act) among poor landless labourer families.

-

Invest in rural livelihoods and agricultural diversification.

-

Expand portability of social protection (PDS, MGNREGA, healthcare)

-

Enforce minimum wages and labour rights in key destination sectors

-

Develop low-cost urban rental housing and sanitation infrastructure

-

Enhance regular district-level monitoring of circular and seasonal migration

-

To establish Bihar as an ‘education hub’, open new universities and medical-engineering colleges in every district, and construct playgrounds, science labs, and modern libraries in all 10+2 level schools at every panchayat.

-

Build All India Institutes of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) and central universities at the divisional level; establish Vikramshila Central University in Bhagalpur, International Buddha University in Bodh Gaya, and a branch of Jawaharlal Nehru University in Patna.

-

Launch an independent probe into corruption in government and connected mafias of past two decades, followed by recovery of the value of all embezzled resources and corrupt proceeds; use that money for welfare schemes to provide relief to poor families.

The writer is an International Professor of Economics. He also serves as the Director of Global South Social Networks and a researcher of Sustainable Economic Development and the Political Economy of the Global South. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.