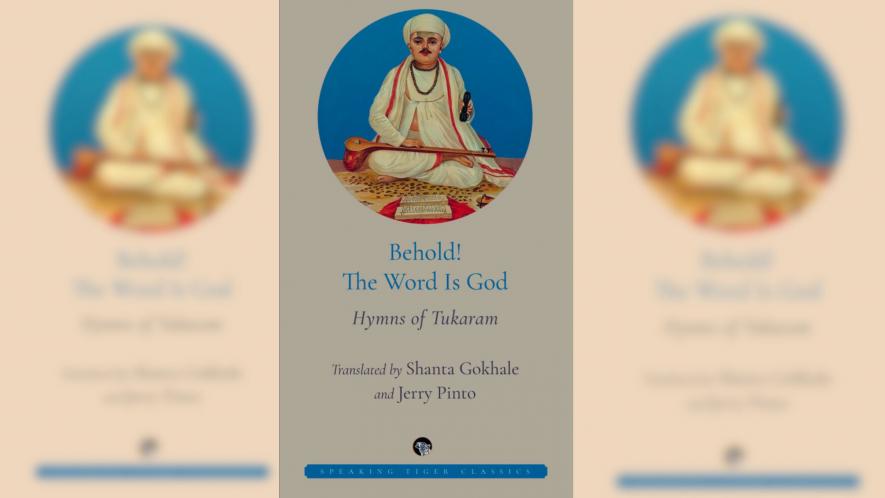

Behold! The Word Is God

Image courtesy Speaking Tiger, 2023

Behold! The Word is God (Westland Books) is a selection of 51 abhangas, Marathi devotional poems by the Bhakti poet Tukaram. The Marathi original is followed by two translations by Shanta Gokhale and Jerry Pinto. The book brings two interpretations of the layered poetry of Tukaram. Both translations offer their unique perspective and flavour to the original. While Shanta Gokhale stays as close to the original in sense, movement, rhythm and form, Jerry Pinto’s translation recasts the abhangas as independent poems parallel to Tukaram’s creations.

The following are excerpts from the book that offer an insight into the translator’s perspective and a glimpse of the original translations.

What Tukaram Means to Me

Shanta Gokhale

Like all great writers and poets, Tukaram calls for multiple translations. Abhangas are written in the ovi metre in which lines are necessarily compact. With Tukaram they are also dense with hidden layers of meaning. Each translator would have her/his own way of unpacking them. It was for this reason that I felt two independent translations rather than a joint one might give readers a better idea of the original.

Moreover, Jerry is a poet. I am not. I assumed that he, as today’s practitioner of Tukaram’s art, might want to do what Arun Kolatkar and Dilip Chitre had done in their translations of Tukaram—recast the abhangas as independent poems that ran parallel to his. My aim as a translator on the other hand, was not to take any liberties but to run as close as I could to the sense, movement, rhythm and form of the originals.

However, in translating the present selection of 51 abhangas, I felt defeated again and again by the sheer weight of the ideas that Tukaram implies but leaves unsaid and the sweet musicality of his language, so difficult to transfer to English. The consonants in English resist flow; the open vowels of seventeenth-century Marathi are made for fluidity. Words like ‘maooli’ are enveloped in soft shades of emotion that ‘mother’ simply does not evoke. Words like ‘triputi’ signal metaphysical concepts that have no equivalent in Western philosophy. As one crawled through these brambles, one had to be careful to keep the precious poems in one’s arms unscathed.

Tukaram’s abhangas, copied by many hands and gathered over many years, fall into no particular order, natural or otherwise. Secretly we are always looking for order. As translators, editors and tellers of stories, we were keen to give our selection a narrative order that would allow readers a view of the abhangas beyond their immediate sense. We realized that our selection fell into three overlapping but distinct groups—Tukaram and poetry, Tukaram and life and Tukaram and Vitthala. We have arranged the abhangas accordingly.

Meeting the Saint

Jerry Pinto

‘Why are we doing this? Because, as Dilip Chitre says, Tukaram belongs to the future. He does, and here we are in that future. Now it might be that Tukaram deserves better than us, more than what we are doing, a deeper incursion than ours. But this is what he has got right now. He will make do. Others will read our work perhaps and say: My gosh, how they skimmed. And perhaps angered or even inspired by that, they will dive deep. Perhaps that is the only reason for us to be doing this, to make someone so angry that they dedicate a life to the poems and bring out an even better translation.

So, my feeling is: We began this project without huge ambitions, we did not want to do something for Tukaram. We wanted, I suspect, to do something for ourselves in this experiment. We wanted to wander as Warkaris down this path.

And so, in the spirit of the beginning, we will tread lightly. We will write no scholarly introductions. We will be naked before our readers, talking solely and simply of our love of the music, the message. We will not set ourselves up as scholars. And we will then let the work set sail on the new river of publishing.

The thing about post-modernism is that it has taught us that we cannot predict the readings, we cannot foretell the responses. My encounters with the world of people who read translations has always been thorny; they are always wondering why you did what you did, why you chose what you chose, could you not have…

That’s all right too.

That’s what one signs up for.

I think we should go on as we have begun, in the spirit of adventure, in the spirit of looking, in the spirit of the jugalbandi which may throw up its own magic.’

And so here are two Tukarams. They come from different worlds, from different histories, from different genders, from different, different, different.

They are united by the love of music, the respect for the power of the word, the desire to bring to you a feast they have enjoyed.

Dive deep now. For could it be you who is meant to take that next great leap of faith?

[…]

Santaanchi ucchhishte bolato uttare

Santaanchi ucchhishte bolato uttare | Kaaya mya gawhaare jaanaave he

Vitthalaache naama ghetaa naye shuddha | Tethe maja bodha kaaya kalle

Karito kavitva bobadyaa uttari | Jhanni majavari kopa dharaa

Kaaya maajhi yaati nenno haa vichaar | Kaaya mi te phaara bolo nenne

Tukaa mhanne maja bolavito deva | Artha guhya bhaava tochi jaanne

My words are lifted from the tongues of saints

I can’t pronounce even Vitthal’s name

I’m a country bumpkin. Ignorant.

I make poems like a lisping child

Scold me for them. I don’t mind.

Remember too my low-caste birth.

I’ll say no more. That is enough.

Says Tuka:

God gives me words.

Their meanings, feelings, he alone knows.

-Shanta Gokhale

My songs are the leavings of the saints.

How could I even know these things?

I can’t get the sound of his name right.

What do I understand?

These songs are a child’s lispings.

You know my worth, you know my birth.

I need say nothing more.

Tuka says: His is the meaning.

His the sense.

-Jerry Pinto

[…]

Aaamhaa ghari dhana shabdaanchicha ratne

Aaamhaa ghari dhana shabdaanchicha ratne | Shabdaanchicha shastre yatna karu

Shabdachi aamuchyaa jeevaache jeevana | Shabda vaatu dhana janalokaa

Tukaa mhanne paahaa shabdachi haa deva | Shabdechi gaurava puja karu

Words are the jewels that fill our homes

Words the tools we put to the test

Words are our breath, life of our lives

The wealth we offer the world as gifts

Says Tuka:

Behold! The word is God

To honour the word is worship.

-Shanta Gokhale

Words, our wealth.

Words, our tools.

Words, life of our life.

Words, the wealth we offer the world.

Tuka says: The Word is God.

The Word be praised.

-Jerry Pinto

This is an excerpt from Behold! The word is God: Hymns of Tukaram, translated by Shanta Gokhale & Jerry Pinto, published by Speaking Tiger, 2023. Republished here with permission from the publisher.

Shanta Gokhale is a novelist, translator, columnist and performing-arts critic. Her Marathi novel Rita Welinkar was published in 1992 and won the Maharashtra State Award for the best novel of the year. In 2009, her novel Tya Varshi also won the Maharashtra State Award for the best novel of the year.

Jerry Pinto is the author of novels Murder in Mahim and Em and the Big Hoom, and the non-fiction book Helen: The Life and Times of an H-Bomb. He has also translated several works from Marathi including Baluta by Daya Pawar, Cobalt Blue by Sachin Kundalkar and When I Hid My Caste by Baburao Bagul.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.