Bihar Floods: Annual Affair of Displacement, Loss and Helplessness

Half-year at Sugar Mill, another half struggling on fields–Sainullah worries for the paddy produce.

Madhav Yadav, who is in his late sixties, is sitting under a hut with thatched bamboo roof and the hay bundled across two layers of bamboo sticks to support and insulate the structure. Fodder for the cattle is kept in a corner; Madhav’s bed is aligned on the other side. Madhav’s memories of 2017 floods are fresh, untouched by any ageing amnesia. Madhav fears for floods this year. ”Ka hogael ba samjhe me naikhe awat. Budhwa ho gaene san lekin aesan badh na hot rala (I feel puzzled to apperceive what is happening… We have never faced any natural calamity like this before),” Madhav says, in Bhojpuri. The Meterological Department has warned of heavy torrential rains in the coming weeks.

Like Madhav, there are 35 other families residing in Padraun village of Laria block of West Champaran district of Bihar, the poorest state of India.

In the month of July alone, more than 90 people died due to the floods in the Northern districts of Bihar bordering Nepal according to official statistics; the actual figure is estimated to be very high. Over two million people of 12 districts of Bihar have been displaced, the flood has left no option for the locals but to flee.

Drying seedlings and rotting sugarcane sound a death knell for subsistence farming in the flood prone region.

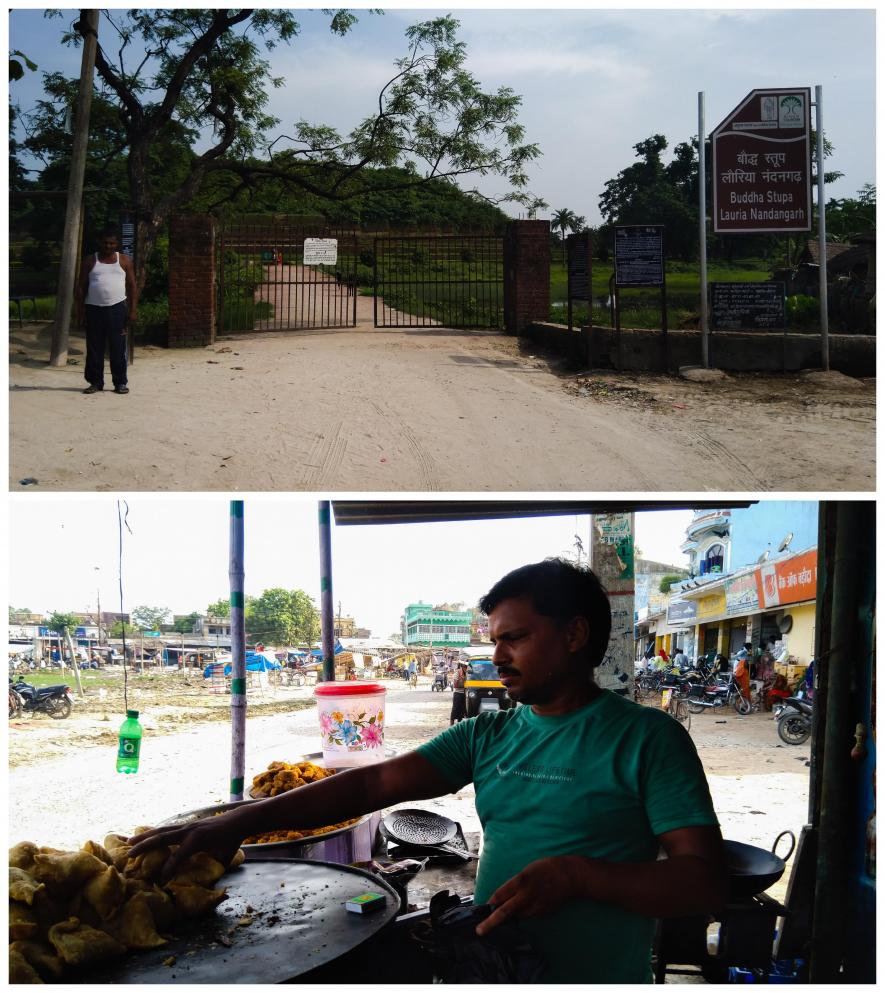

However, the villagers of Lauria are unwilling to vacate the area as they believe that Lauria-Nandangarh Buddha Stupa is to their rescue. The 26-metre-high huge Buddhist sepulchral mound traces its roots to Ashoka who ruled this region in third century BC. It is conjectured by the archaeologists that the ashes of Lord Budhha were enshrined here.

Vilash Yadav, who has just returned after labouring in a nearby village for a wage of Rs 100, tells NewsClick that the villagers climbed to Nandangarh Stupa in 2017 floods for safety, they will do the same if the floods hit the village again.

Vilash Yadav has lost more than an acre of paddy crop, he now plans to move outside of state to work as a manual labourer to earn some money.

Vilash lost 15 katha (10,800 sq. ft) of paddy crop due to incessant rains this year. He says, “I bought the costly seeds thinking that it will give a good yield. I had no idea of this impending havoc.” He took this stretch of field on an informal contract of adhiya bataiya [a type of sharecropping where the tenant farmer has to give the half of produce to the owner]. Now, Vilash is worried as he will have to pay some compensation to the land owner. He adds, “Most of us here [in Padraun] have just the land to put a house in place, nothing other than that. We are landless.” No one in the village knows about the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY), the multi-billion flagship scheme of the Modi government to insure farm produce. Illiteracy, too, is ubiquitous in the flood-affected region, depriving the victims any knowledge of their rights.

There is a famous sugar mill within the radius of a kilometre of the flood-prone area. Lauria Sugar Mill, operated by Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited (HPCL) in the winter season, intakes the sugarcane produce from this region. Vilash still awaits the payment for 13 trailer-trucks of sugarcane which he delivered to this sugar mill, aggravating his woes. He laments, “I have lost all hope. We are traditional dairy farmers, but we can’t do it now.” Yadav is a caste name for traditional dairy farmers but none in this village have cattle as a source of income.

Vilash had more than 10 cows when he was young, but now is left with a single cow. He sold the cattle keeping in mind that he will not be able to protect them during the floods. “There is no grassland. People have been flocking to this area after the sugar mill started functioning,” he says. Many settlements have surfaced here in the recent past thus inhibiting the smooth percolation of water into water table.

Vakil Miyah, a landless butcher, received housing scheme funds after ten years of consistent appeals.

Vakil Miyah, a butcher, sells meat in the town market of Lauria. As he is gearing to reach the town before evening market flourishes so he can make a good profit, he takes out some time to talk to us: “What do we have? This hut painted with mud, what else? If I don’t earn today, my family will have to sleep hungry.” After a struggle of more than a decade, he has finally received the funds under the housing scheme meant for poor. For this, he allegedly paid a bribe of Rs. 10,000 to the village head. Vakil’s anguish at this is plain—the rampant corruption in government offices has pushed the poor to suffer. When it comes to floods, it adds insult to injury.

Vakil Miyah’s neighbour Santima Devi’s story is no different. Moreover, there is a twist. Santima had exchanged money for land with a local landowner. Rehan is the colloquial term for this barter. Landless Santima will have to leave the land as the landowner returns the money, the credit is returned without an increment. “He [the landowner] will not return my money with an interest. I have already lost crop in the floods,” Santima continues, “We poor will always remain poor.” Santima belongs to the Other Backward Class (OBC). The landowners here are of upper caste stratum who have started pursuing this technique of barter after the flood has become a routine concern.

Sainullah Ansari, 26, works on a contract in sugar mill for which he receives Rs. 15,000 between winter and spring, till the time sugar mill operates. On the other days HPCL, a public sector undertaking (PSU), leaves many like Sainullah unemployed. In these dormant months, Sainullah concentrates on his 6 katha of land where he grows paddy. Like many others in the village, is a subsistence farmer. Sainullah says, “Farmers are not left with surplus to transport to market to cash some rokara (spondulix). We will try to sow seedlings again if water goes way. If it rains again, we are shattered. We will have to buy rice from the market.”

The prices of cereals fluctuate after floods. The reason is simple–the shortage of stock. The rice which is sold at Rs. 25 per kilogram, Sainullah says, will shoot up to Rs. 35.

Two goats and one chicken are the alms for one Vindheshwari Yadav, who borrowed her name from her husband after marriage. “If there will be scarcity of vegetables during floods, we will have to sacrifice them [animals],” Vindheshwari says. Tairun Khatun, a widow, is raising four children on the farm output of 3 katha of land exchanged on rehan. She says, “We haven’t received the flood recovery pay for 2017 floods yet. Upper caste people living in the other village have received it; some people having good contacts with the village head also were given funds for recovery.” She questions, “Why were the poor left?”

Vilash’s son Mulayam is running a small general store near the entrance of Buddha Stupa. He is pursuing humanity courses in Grade XI in a government school. Mulayam says, “I study here in the shop [pointing to notebooks behind him] when I am free. Floods have worsened the situation, but somehow, we have to manage. I have to bring in a change, which is why I am studying.” While Mulayam takes his notebooks to revise from notes, Mulayam’s father Vilash is preparing to leave for New Delhi where he will work as a manual labourer. Vilash plans to return by November to celebrate the festival of Chhath, with earnings sufficient to support the family of nine for a few months.

Birchha [top] lost his land to archaeological site while landless confectioner Durga [bottom] awaits yearly floods.

The infrastructure near the archaeological complex is in tatters. Government has failed to develop it as a tourist location. “If government had worked on tourism,” says Birchha Yadav, “we could set up hotels and restaurants here.” “Uhe se jathi amdani ho jait (It could supplement our paltry farm income.)” Birccha, 38, lost the legal right over a piece of his land to the archaeological complex. Government has never paid any compensation, he says.

Not only residential area has been inundated by Gandak river, but also the wildlife has diminished significantly. Situated at 70 km from Nandangarh in Northwest is Valmikinagar National Park or Valmiki Nagar Tiger Reserve (VTR). The park, which shares boundary with Nepal, is home to 40 endangered Bengal tigers, more than 5,000 other mammals, 1,520 birds and 32 reptiles. Forest Ranger Centre No. 7 of VTR is under water, anti-poaching rangers feel incapable to venture out in floods. Awadesh Prashad Singh, the in-charge of Madanpur Forest Division has written to the Department of Environment, Forest & Climate Change, Gov. of Bihar, highlighting the poaching threat to some six tigers and other animals who are in this region. He says, “Floods have affected our regular patrols. We are somehow managing with the help of the boats. As tigers are good swimmers, they may travel to the dry area. The actual threat is not the flood but the poachers who prey on them. For the other animals, it is certainly a critical situation.”

Professor Anil Kumar, who teaches hydrogeology at Patna Science College, is of the view that the floods in this plain are man-made. He tells NewsClick that the deforestation, population outburst and unsustainable development are the prominent reasons behind the floods. With the population outburst, Kumar says, the ponds and wells disappeared as people started utilising these lands for agricultural and residential purpose. Kumar details the traditional water harvesting system: “Earlier, people were mostly dependent on surface water. Ground water was almost insignificant in use. In contrast, we have a handpump in every house now. Surface water is rarely used. Second, the discharge of untreated water in mainstream generates huge amount of sediments, brimming the river-tract. Natural recharging system for the aquifer has been disrupted because of settlements and industries.” Kumar believes that “the dams constructed on rivers in this [North Indian] plain are strictly unsustainable”.

The locals say that Valminikanagar Barrage has disturbed the natural order, year by year the floods are intensifying in the region. Valmikinagar Tiger Reserve is facing threat from poachers.

The area has been tagged a flood-prone region a few decades ago, this was never an inveterate situation here. Residents of Harnatanr and Bhainsa Lotan villages agree that the construction of Gandak barrage in 1964 has disturbed the natural order, further adding that “floods have become quite common in the region now”.

Durga Shah, a traditional confectioner, runs a sweet shop near National Highway 28-B, a few kilometres away from Burhi Gandak river. He tells us that he lost grains worth Rs. 6,000 because of the downpour this month. Also, he was a victim of 2017 floods. Durga says in his sibilant voice, “Water level was 6 feet high. My shop was submerged. There was water in my home as well. I saw my hard work and investment drowning and couldn’t do anything. This has become a yearly chapter for us.” Shah’s shop is much smaller now, less amount of sweets and no helping hand. He prays to the god to not devastate the region with floods this year.

National Water Development Agency (NWDA), a body of Government of India (GoI), is working towards the inter-linking of Indian networks by a complex channel of reservoirs and canals, reportedly, to reduce floods. However, NewsClick learns from the scholarly research of Prof. AK Misra of Sikkim University that the central government has not developed a sustainable framework for the project. The paper argues that “the river-linking will not only allow the prevention of the colossal wastage of a vitally important natural resource, mitigate the flood and inundation by detaining flowing surface water of rainy seasons, but also ensure availability of water to drier areas; combating both flood and drought simultaneously.” The condition remains– “the project should be scientifically sound”. By this, Prof. Misra means that lithological constraints, geogenic issues and hydrogeological reality must be logically addressed. Misra et al. argue that the regimes of Himalyan rivers is monsoonal as well as glacial while groundwater-fed perennial rivers are solely controlled by rainfall. The interlinking will challenge the natural order without any pragmatic planning to counteract the drastic changes interlinking will bring. Geogenic issues like mixing of life-threatening arsenic or other pollutants in non-arsenic channels will threaten much greater part of the sub-continent. Further arguments of the paper are on cementation property with extremely low porosity and permeability of Vindhyan basin, Cuddapah–Kurnool basin, Chhatisgarh basins and Western Rajasthan basins where groundwater recharge through river interlinking will be minimum, thus defeating the purpose of water supply. The large portion of the states Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh belongs to the Deccan trap with almost nil porosity which again would not serve the goal. There is no doubt that the inter-linking project hasn’t addressed these distinct hydrogeological realities of the country. Also, the project doesn’t clarify how it aims to control flooding.

Chandra Bhushan, Deputy Director General of Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), insists that floodplain management as a stratagem against extreme torrential rains in catchment areas of Nepal is somewhere missing, resulting in excessive flooding.

Bhushan confirms that “embankments have played an important part in intensifying the floods.” He says, “It is estimated that the flood-prone area in the state has doubled after the construction of over 3,000 km of embankments. Embankments trap the silt and sand on a narrow river bed thereby increasing its height vis-a-vis the floodplains. As embankments often fail, a large amount of water gushes out leading to sudden flooding.” According to Bhushan, Bihar is a flood-prone state and because of climate change, the region will see more intense rainfalls. “We, therefore, need a solution that recognises the hydro-geological reality of the state. There is not going to be one solution. We will need to improve the ecology and enhance the drainage systems so that the flooding is moderated and the floodwater moves out quickly. Disaster management will have to be further strengthened to save lives,” he adds.

In fact, the reason behind 2008 Kosi floods was an embankment breach. But the breach was not anticipated nor given any priority. An acclaimed research on Kosi attributed the breach to “the sheer absence of monitoring and maintenance of embankments, the hierarchical communication mechanism, and the exclusive and complex nature of the institutional design for dealing with the Kosi”. Moreover, Shrestha et al. agreed that the incomprehensive Kosi treaty was at fault and proposed the redesigning of institutional arrangement to improve decision-making processes and communication processes. After a decade of disaster caused by Kosi, the Bihar’s sorrow, the political system remains in doldrums. The treaties with Nepal on several tributaries are either missing or poorly executed. This year’s floods are a fresh testimony to it.

Study conducted by Chander Prakash and N. Nagarajan shows a persistent threat of Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) in Chandra Basin in Lahaul-Spiti district in Himalchal Pradesh, a northern state of India. Prakash et al. conclude that “the continuous expansion of lakes and glacier retreat” is the reason behind the threat. Basnett et al. link the glacial ablation rate with climate change and global warming.

Ajaya Dixit, in his research, illustrates the direct relation between 2008 Kosi floods and GLOF. He explains: “The rapid retreat of glaciers in the last half of the 20th century has often formed ice-core moraine-flanked lakes of melt water. Occasionally, a moraine dam breaches and a lake empties in a very short time. The result is floods of great magnitude in downstream river reaches. The water carries with it sediment from the moraine dam as well as earth from the riverbed and banks gouged out by the flow. The combined action of sudden flooding and debris movement washes away riparian farmland, settlements, infrastructure and many unsuspecting individuals in its wake.”

Dixit writes that “the GLOF is also a major source of sediment load”. Kosi which is brought to terai plains at Chatara, Dixit writes, with sediment load starts moving laterally because of deposition of coarse sediment load on the inland deltas. “As a result, the Koshi has an extremely high flux density and is, hydrologically speaking, a very violent river,” Dixit adds. This contributed immensely to the embankment breach which unfolded intense flooding Sunsari district of Nepal terai and in six districts of north-east Bihar of India: Supaul, Madhepura, Saharsa, Arariya, Purniya and Khagariya.

Another study shows the GLOF risk in Kosi river basin in Himalayas. Thus, with the climate change in action, expansion of GLOF may induce a disaster in the Himalayan regions of Indian subcontinent through water circulation.

Aditya curiously looks outside of the bus window to see the how rains have left fields clogged with water.

As this reporter boards the bus, he finds co-passenger Aditya, 7, commuting with his family from his home in Ramnagar to Bettiah where Aditya’s elder sister lives. They plan to return after the situation normalises in their village in the distant north-west of Bihar. Asked about the seasons Aditya loves, he says that rainy season is certainly not one of them.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.