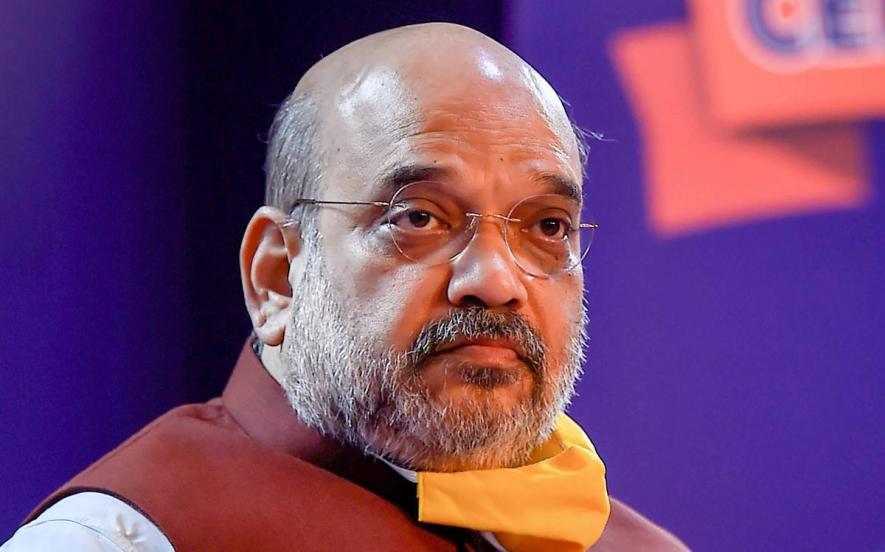

Why Wishing Ill on Amit Shah Should Alarm Everyone

Image Courtesy: The Hindu

A nation polarised over Home Minister Amit Shah’s prolonged treatment for the Covid-19 illness in hospital, from where he was discharged last week, does not surprise, given the gulf between Hindutva supporters and their opponents. But what does come as a surprise is that the opponents of Hindutva seem headed to become what they hate. They breathlessly monitored on social media whether Shah’s health had deteriorated, evident from tweets asking people to expect “good news” from a Delhi hospital, at times even hoping he did not recover from his illness.

Wishing ill on a person or celebrating his or her death has been one of the defining traits of Hindutva trolls. When journalist Gauri Lankesh was shot dead in September 2017, Nikhil Dadhich tweeted, in Hindi, to say, “A bitch died a dog’s death.” He mocked those lamenting her murder. Among the followers of Dadhich is Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Tweets such as Dadhich’s had Union Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad to deplore “the messages on social media expressing happiness on the dastardly murder of Gauri Lankesh.” It, in turn, provoked a former All India Radio presenter to remark, “Bowed down to media, secular and liberal bullies? We work for you tirelessly, selflessly. This is the reward.” This handle is also followed by Modi.

Hindutva’s return to power in May 2019 has not had its supporters mend their ways. They celebrated journalist Rana Ayyub testing positive for Covid-19. Sundanda Roy tweeted, “Big Breaking: Rana Ayyub is no more.” An irrepressible Ayyub shot back, “Sorry to disappoint you.”

Hindutva supporters alleged she was faking her Covid-19 report, with @divya_16 claiming, “If @RanaAyyub can lie so brazenly about being Covid positive, imagine how much she lied after 2002.” To this, Ayyub responded, “This twitter handle is followed by the Prime Minister of India, I rest my case.”

Illegitimate measures

The virus of hate seems to have now infected the opponents of Hindutva, who claim that unlike their rivals, they believe in democracy, debate and dissent. They have always decried, rightly so, the violent tactics of Hindutva supporters such as lynching and the intemperate language they use. Yet their reaction to Shah’s weeks of stay in hospital vividly displays their own transformation. They are gradually becoming them, not in action, but in their imagination and the language they employ.

People wishing for someone to die signifies their own disenchantment with the reality, which they feel they cannot change. In contemporary India’s context, those who wish ill on Shah are unconsciously expressing their own helplessness, their inability to vanquish Hindutva, of which Shah is a popular face. They are impatient for victory, yet also sense the futility of their endeavour.

Their sense of futility arises because of their perception that illegitimate measures are undertaken to thwart them, to weaken them for all times, to have them perpetually languish in a state of helplessness. This perception is formed by instances such as the arrest of human rights activists on charges palpably specious, as in the Bhima Koregaon case, or the motivated investigation into the Delhi riots that has led to the incarceration of those who had peacefully resisted against the government’s citizenship policy.

Thus, those who wish ill on Shah perceive him as the principal proponent of illegitimate measures, not least because he is the Home Minister. Guilt does not gnaw them because implicit in their wish is the desire to save the nation, which has had many of its existing social chasms widened by Hindutva, deliberately and insidiously—and sought to be made permanent.

The moral argument

Wishing ill on a person in power is a phenomenon not peculiar to India. Philosopher Kasper Johansen, in a blog, confesses that after the election of Donald Trump as American President in 2016, he has been philosophically concerned about the moral dilemma of wishing ill on another human. Johansen asks, “Is it morally wrong for me to wish for Donald Trump to fall ill in one way or another? That he gets very sick? Or what about the more extreme, wishing he would die?”

The ethical-philosophical branch known as deontology posits that it is always wrong to kill another human being no matter what. But Johansen tosses a question for us to mull: Would it have been wrong for a person to kill Hitler before he began to persecute the Jews and went on to trigger World War II? But then, how could the person have predicted the future under Hitler?

Since it is impossible to decipher the future, there is no way of knowing Trump would cause the death of, say, six million people, the estimated number of Jews who perished because of Hitler. “So you would be morally wrong in wishing him [Trump] dead,” Johansen concludes, although he says it might not be wrong to wish him a “tiny bit of ill-will”—for instance, hoping all his projects are dismal failures.

The cultural argument

What is morally wrong is also culturally defined. In India, for instance, obituaries rarely mention the darker side of the deceased. People who wish death on their foes invite withering looks or condemnation from others, an example of which was Prasad publicly ticking those celebrating the death of Lankesh. Or Karnataka’s Congress head, DK Shivakumar, who tweeted to restrain his party cadres wishing ill on Shah: “It is not in our culture to wish bad for others.”

Even Shah resorted to the cultural argument to silence those who he said were “praying for his death.” Shah’s public appearances during the lockdown had become so rare that it sparked wild rumours about his health. On 9 May, Shah tweeted saying he was healthy, and that he had chosen to scotch rumours because his party supporters were worried about his health. He added, “According to Hindu thought, such rumours about a person only bolsters his health. I hope people will not engage in such useless talk and will let me do my work and also do their own work.”

Illegitimate passions

It is hard to recall whether Shah has ever restrained the Hindutva trolls from baying for the blood of its opponents. Certainly the Prime Minister following the purveyors of hate on social media is not the prescription for reining them in. The use of hate language, in fact, seems to have become a qualification for growing in the Bharatiya Janata Party. Tajinder Pal Singh Bagga assaulted lawyer Prashant Bhushan in 2011, and was made, six years later, the spokesperson of Delhi’s BJP wing.

Yet, in the eventuality of the opponents of Hindutva becoming what they hate today, India will become a Republic without hope. Violence will become the mode of debate as well as the favoured method of expressing dissent. The many chasms that Hindutva has crafted or widened will become unbridgeable. The opponents of Hindutva will themselves become swaggering bullies, justifying and engaging in violence.

It will likely be said that only an alarmist can perceive twitter messages wishing ill on a politician as ominous. Yet for so many people to have the same thoughts of ill-will at the same time creates an ecosystem for the hurt and angry, the helpless or the twisted soul to harbour illegitimate passions. Such a thought is chilling to contemplate.

The author is an independent journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.