Why Land is Meaningless Without People Who Inhabit it

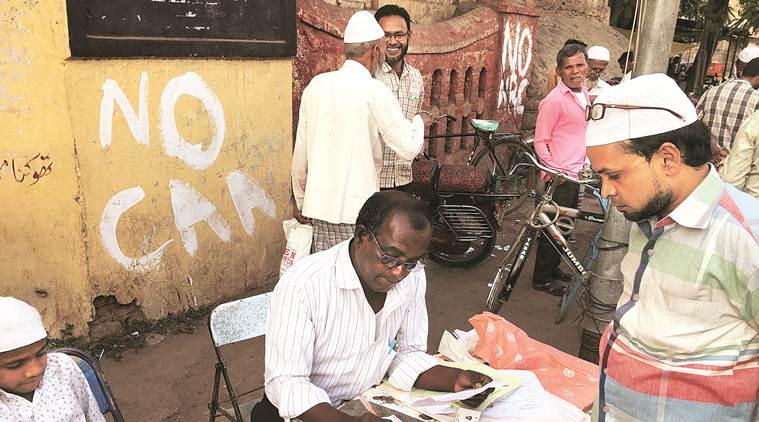

Image for representational use only.Image Courtesy : The Indian Express

No piece of land will ever hold meaning if not for the people who inhabit it. People will belong where they would like to, where they actually do, where their communities do, where their loved ones do—be it Kashmir, be it Assam, be it JNU. Because the human relationship with land is far more intricate, intimate and complicated than a government-stamped birth certificate.

Is there a relationship between land and its people? Does land belong to people or do people belong to land? Do I belong to a particular land or many lands? Do I necessary belong to the land I was born in? Is it necessary to belong to any piece of land at all? Can I grow independent relationship with land(s) other than where I grew up? Is it obligatory to have a relationship with land? Does the relationship demand love? Does it demand hate? Does it demand indifference? What is it between humans and land after all?

Such questions are fundamental to human history. Despite that, these are no rhetorical questions. It is imperative, in fact, that we ask these questions to ourselves time after time, especially because the Indian state wants us to kill each other in the name of land. Whose land is it anyway? Does a piece of land rechristened as nation-state belong to the state, the people who live there every day, the people who visit there as tourists, the people who do business there, or the international body authorised to demarcate lands and draw borders between them? These are simple questions with complicated answers, perhaps. But these are questions we cannot avoid any more.

With a fascistic government taking India down the road to perdition, by introducing draconian laws on one hand and brainwashing the people with manufactured consent from the media on the other, we ought to ask—is the landmass demarcated as ‘India’ for the people who live there or otherwise? Do we live to safeguard just a piece of land or for the sake of the community life around that landmass? If a land is just a piece of land sans its people, it is instrumental, it is rugged, it is crude. Also, it is anonymous. No piece of land will ever hold meaning if not for the people who inhabit it. Imagine river banks without habitation, hill-tops without its people, valleys without villages. What are we left with then? Just landmasses with basic topographical characters.

Coming back to the questions, humans have intimate relationships with land. The land she was born in, the land she grew up in, the land she moved to. This sentiment is universal. In view of that, how inhuman we have to be to prioritise printed papers over human lives, human habitation. Falling prey to the fascist state is fast robbing us of the personal, intimate relation we share with surrounding lands.

The human relation with land is fundamental to human history—we learnt to grow food that grew on the land, we learnt to light fires by stroking two pieces of land against each other, we invented the wheel to travel across the land. There is no denying human being’s organic relationship with land. At the same time, there is no denying that these mega historical events would mean nothing if humans did not have communities to share their knowledge with. Hence the human relationship with lands holds true only with reference to her relation with other humans.

Human history is the history of migration. Migration as a phenomenon epitomises the ambiguity of the human-land relationship. Historical narratives teach us that almost every human today is a migrant. Then who will show papers to whom—to prove what—how does one prove her relation with a landmass unless the other humans she has shared the life there with vouch for her existence? Can we ever prove belongingness? Can we ever—effectively—deny people the land that they crave to belong to? We cannot, at the end, even by brute force. So we can enforce silence upon Kashmir by shutting the internet down, but for how long? We can kill septuagenarians in the detention camps in Assam but how many? We can beat students in public universities black and blue but with what impact? People will belong where they would like to, where they actually do, where their communities do, where their loved one do—be it Kashmir, be it Assam, be it JNU. Because land is not just synonymous with state, nation, nation-state, country. Because land is about belongingness and that could be anywhere. Because human relationship with land is far more intricate, intimate and complicated than a government-stamped birth certificate.

The author is an ex-JNUite who teaches gender and migration at the Global South Studies Centre, University of Cologne, Germany. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.