What Explains Spate of Suicides by Rape Victims

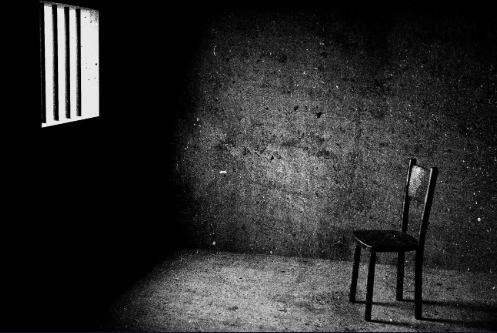

Sexual violence is widespread in India. In just one year, 2016, nearly 40,000 rape cases were reported across the country. Even so, activists claim that the reported cases are only the tip of the iceberg. Of late, another sign of the rot in the criminal justice and investigation system, with respect to crimes against women, has emerged. This is reflected in the spate of suicides by women and young girls after they have alleged rape. In many of these suicide and attempted cuicide cases, the families of the deceased victims have accused the police of not investigating the victim’s complaint or refusing to register her complaint at all as the reason for her extreme step.

For instance, a recent report from Muzaffarnagar in Uttar Pradesh details a gruesome series of events. A 24-year-old woman despaired after rape charges leveled by her were not pursued by the police. She died of self-inflicted injuries, but on on the walls of her home and on her own hands were found scrawled the names of the alleged perpetrators.

Not just this case. In many such recent incidents women have taken their lives as a last resort to highlight their travails and police apathy. Shruti Kumar, who teaches at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, says that girls are taking to self-immolation as a means to get justice. “They have suffered so much pain, horror and indignation and they feel this is the only step left that they can take,” she says.

The irony is that in most such cases where the woman commits or attempts suicide, the police rush to register a First Information Report or FIR posthumously, which was usually the victim’s primary demand in any case.

In Uttar Pradesh, at least three women have attempted suicide after the police refused to register or take their complaints of rape seriously. These include a teenager, only thirteen years old, in Kanpur. She killed herself at home after returning dejected from the thana. Another rape survivor and her mother similarly tried to self-immolate in August this year at Unnao’s Makhi police station. Such is the callous indifference of the police that this is the same region where the infamous Unnao rape had taken place, which the Supreme Court has been watching over.

Of course, even the complainants in the so-called high-profile cases of rape reported from Unnao and Shahjahanpur, where the alleged perpetrators are powerful Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leaders, had threatened to end their lives unless the police registered FIRs and launched investigations into their complaints. At this stage, the Supreme Court had intervened, and the police had been prodded into taking action.

A gangrape victim from Hapur in Uttar Pradesh also died after the police refused to file her complaint. This woman had gone to the police station on 23 August with her husband, where the officers had insisted on a settlement with the alleged perpetrators, who were from the same village.

Ultimately, after her death, the police turned her written complaint into a FIR. She had alleged gruesome rapes that had gone on since 2014. She died at a hospital in Shahjahanpur after she set herself alight at her home. There was even a viral video that showed the woman accusing Hapur Police of inaction. The Superintendent of Police (SP) of Shahjahanpur, S Channappa, admits to “lapses” by the police and that the complaint should have been registered immediately. He says that several police officers were suspended after her suicide.

Anybody would say that registering a posthumous complaint in a serious offence is too little, too late. Yet, the number of such cases appears to be very high. Former Deputy Inspector General (DIG), Uttar Pradesh, Prakash Singh says that the main reason why FIRs are not registered is because there is pressure from the government on the police to keep the crime statistics low. “It is for this reason that there is an attempt to doctor the figures and to show only marginal fluctuations. But a rise in crime is bound to happen,” says Prakash Singh.

What Singh points out is essential to understand the state of policing: Instead of trying to check the incidence of crime, it is bent on checking the number of crimes that are registered. This amounts to window-dressing even serious crimes—and much of this distortion comes at the cost of women’s sense of security, safety and justice.

For example, in May, a woman from Babugarh, also in UP, reported that she was sold for Rs10,000 by her family and thereafter sexually assaulted. The incident took place in 2016. After the police in two different jurisdictions refused to register her complaint, she attempted to kill herself. When she landed in a Delhi hospital, Swati Maliwal, who heads the Delhi Commission for Women (DCW) had written to the UP Chief Minister, Yogi Adityanath, seeking help for the woman.

The spate of suicide attempts is not limited to UP. On 28 July 2019, a Jaipur-based woman died after she tried to kill herself at a police thana premises. She claimed rape by persons known to her husband in 2015. The police had been asking her to withdraw the complaint. Her husband, too, wanted her to revoke her complaint and refusals led to threats. As all of this was ignored by the police, she poured oil on herself at the office of Kanpur SSP, set herself alight, and perished of those injuries in a hospital.

Even after this, the police remained apathetic, as an investigation by the National Commission for Women (NCW) later found: The woman had perished of her injuries, but the statement of her son had not been recorded on time.

Ranjana Kumari, who heads the Centre for Social Research points out, “We presently have 100,000 cases of rape pending in our law courts. Many are five to ten years old. We would like to know in how many cases have cops been jailed for not filing FIRs. Not a single cop has been arrested so far in any state of our country,” she says.

Women seem to have been left with very few options, which explains the rising graph of rape victims’ suicides. As professor Shruti Kumar says, “The police are an extension of our society. They can belong to the caste of the perpetuators. In other cases, victims are threatened and become unwilling to pursue cases. This can be seen as an exercise of power against a particular caste group.”

The criminal shortcomings of India’s law implementation were highlighted in the so-called high profile cases reported from Shahjahanpur and Unnao. Yet, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of instances of police indifference and insensitivity. The 23-year old law student from Shahjahanpur actually had to go public about being sexually assaulted by a BJP leader, the former minister for internal affairs, Swami Chinmayanand. She had provided police with recordings of his actions and yet it is she—not the accused—who was arrested first on charges of extortion. In the meanwhile, Chinmayanand was admitted to a hospital.

Former top cop Maxwell Pereira is horrified by the events. In effect, he points out, the law student was jailed while the accused recuperated in a state- of- the art medical facility. “Even if there are question marks over the extortion issue, when an individual is allowed to murder in self-defence, why can the same person not resort to blackmail as a form of self- defence,” he asks, rhetorically.

In any case it is Chinmayanand who had resorted to black mailing first: he had allegedly had a video taken of the complainant without her knowledge or consent, as her lawyer has disclosed.

Finally, Chinmayanand was jailed but the police are playing down the rape and focusing on the extortion. They have charged him with “misusing authority for sexual intercourse” and “sexual intercourse not amounting to the offence of rape”, which carry lower penalties under the law. Rape invites a minimum seven-year term to a life term in prison while the charges actually levelled against him carry a jail term of five to ten years.

If not for the Unnao rape victim’s steely resolve not to withdraw her charge against the former BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar, nothing would have come of this case either. She, too, had tried to self-immolate outside Adityanath’s official residence in response to the system failing her. The SC ordered that the case be transferred to the CBI which is now handling it.

When Nirbhaya died, the courage she had shown before tremendous brutality had horrified the public. But for many other thousands, it takes raw courage just to file a complaint. Where do they go from here?

Rashme Sehgal is an independent journalist. Views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.