Tractor Parade Versus Republic Day Parade: Clash of Symbols

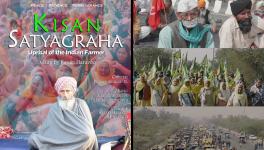

The farmer tractor parade, scheduled for 26 January, will create symbols in sharp contrast to those the official Republic Day parade on Delhi’s Rajpath has crafted and perpetuated over the last 72 years. For the first time, the state’s veritable monopoly over Republic Day celebrations will stand challenged. For the first time, the parade on Rajpath, organised and financed by the state, will have to compete with a civilian one for the nation’s attention.

It is impossible to match the parade on Rajpath in its pomp and show. Nor its VIP quotient. Nor is it possible for any parade around the country, civilian or official, in state capitals and Union Territories, to match the viewership of the one on Rajpath, not least because it is telecast live. And yet, on this 26 January, many will want to know how the tractor parade fared. Underpinning their curiosity would be the realisation that in its very conception, the tractor parade has created, consciously or otherwise, a set of symbols inviting multiple readings.

Those curious will likely be aware of the unceasing debate on whether Republic Day should be celebrated with an unabashed display of India’s military prowess and acquisition of latest killing machines. 26 January, after all, is celebrated because on this day, in 1950, the Constitution came into force and India formally became a sovereign democratic Republic. Does India’s sovereignty have to be projected through its military? Yes, argue many, the Republic cannot survive without the military’s protection. From their perspective, the parade on Rajpath assures Indians about the security of their Republic.

This debate will acquire a new dimension because of the tractor parade, which communicates the message that the Republic survives not only because of the defence forces; the Republic also survives because of the backbreaking work that farmers undertake to feed the people. While soldiers make the Republic secure, it is nourished and sustained by farmers. It is they who made India self-sufficient in food, prompting us to recall those bygone years in which shortages of foodgrains had Indian Prime Ministers beseech the Great Powers for succour. That memory, rekindled because of the tractor parade, will prime us to listen to those who argue that the three new farm laws will, with time, weaken the public distribution system, lead to food inflation and shortages, and compromise the Republic’s independence.

It is still not known whether Delhi Police will allow the farmers to take out their tractor parade on Delhi’s Outer Ring Road, which loops around the Capital. At the centre of the circle enclosed by the Outer Ring Road are the offices and mansions of those who rule over India. This places the parade on Rajpath in the rulers’ forecourt. By contrast, the Outer Ring Road is the periphery, from where the dissidents, as farmers certainly are in today’s context, will, on 26 January, warn the rulers that they must reform themselves. The locations of the two parades have symbolically brought into play the centre-periphery conflict, a theme that predates even the emergence of the modern nation-state.

The periphery comprising farmers will, through the tractor parade, offer their own ideas of what the Republic ought to be. To begin with, it must be egalitarian. Ponder over the contrasting pictures: The President, as the commander-in-chief of the Indian armed forces, takes the salute at the Republic Day parade on Rajpath. No one will do so during the tractor parade, which, in effect, flattens hierarchies. Rajpath, on 26 January, will witness 32 tableaux, all officially imagined and designed. Some of these will display the unique culture of the States. Farmer unions have claimed they too will take out tableaux, imagined and designed by them, presumably foregrounding the people’s imagination of the Republic and its myriad cultures. Or, perhaps, to convey the message that the “best culture is agriculture.”

The battle of symbols will not end there. Before the President takes the salute, the tradition is for the Prime Minister to lay a wreath at the Amar Jawan Jyoti, to commemorate soldiers who died doing their duty for India. The Samyukt Kisan Morcha, the umbrella organisation of over 40 farmer unions, has cited the death of their 143 comrades during the ongoing protest to reject the Union government’s offer to put on hold the three new farm laws for 18 months. “Their sacrifice will not go in vain and we will not go back without the repealing of these farm laws,” an SKM press release said on 22 January. The deceased farmers will certainly be remembered as martyrs on 26 January, as martyred soldiers too will by the Prime Minister.

The official parade relies on the collective memory to convey that India’s weaponry system has acquired tremendous sophistication over the decades. The tractor parade will do likewise—it will convey rural India’s technological evolution from the era in which the bullock and the plough symbolised agriculture. If the Pinaka multiple launch rocket system, which is to be displayed during the parade on Rajpath, has augmented India’s defence, the tractor has enabled farmers to acquire a degree of prosperity. Indeed, the tractor signifies the farmer’s capacity to manage and master modernity.

Above all, the tractor parade tacitly interrogates the opening line of the Preamble to the Constitution, which reads, “We, the people of India, having solemnly resolved to constitute India into a Sovereign Socialist Secular Democratic Republic…” With the people constituting India into a sovereign Republic, does the right to make laws vests in their representatives? Is it incumbent upon the people to accept the laws they make? No, argue the farmers, the elected representatives cannot make laws inimical to them, precisely because the sovereignty is constitutionally vested in them. It is to reclaim this sovereignty and, therefore, also the right to determine the efficacy of laws, that farmer leaders have chosen to pitch their tractor parade in competition with the official Republic Day parade.

This view of farmers echoes, in many ways, the arguments cited by Mahatma Gandhi to launch the Dandi March, in 1930. He said the British government could not enjoy the monopoly over the production of salt, apart from imposing an inordinately high tax on it. The protesting farmers say the government cannot implement laws that they feel undermine their interests; and that the three farm laws must be repealed before they and the government together devise a set of legislative measures to address the prolonged agriculture distress. Just as the salt laws were framed to favour British imports, so too the three farm laws have been designed, from the farmer’s perspective, to promote the interests of giant corporates. The tractor parade is the 2021 equivalent of the 1929 Dandi March.

There was a reason why even though the Indian Constitution was adopted on 26 November 1949, it was brought into force on 26 January. During the 1929 Lahore session of the Congress, the national leaders had declared that the last Sunday of January 1930 would be observed as Independence Day. That Sunday happened to be 26 January. With India gaining Independence on 15 August 1947, the memory of the Lahore session was consecrated by declaring 26 January as Republic Day. Through the lens of history, the tractor parade on 26 January becomes, at once, a celebration of the collective will, of establishing its supremacy over an elected government inclined to behave imperiously.

The author is an independent journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.