Punjabis in India, Pak, Yearn for More Than Gurudwara in Kartarpur

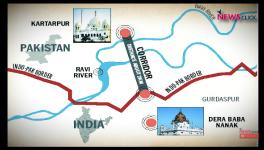

Typically, in the autumn season, the rabi sowing of wheat fields takes over the thrum of life at Dera Baba Nanak, a kasba in Punjab along India’s border with Pakistan. But this year, residents tended their fields with a special sense of anticipation. To mark the 550th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak Dev, the founder of Sikhism, India and Pakistan will be bridging the distance between their homes and an important Sikh pilgrimage site two kilometers away.

On the eve of the opening on November 9, Indian political parties have set up various grand tents and podiums in this tiny town. And Pakistan is sprucing up the site in Kartarpur so that pilgrims walking or driving in from India get a magnificent full view of the Gurudwara Darbar Sahib located there. The thought of seeing their holy site has the residents of Dera Baba Nanak in India excited. Yet, the pilgrimage is just one reason for their feeling overjoyed.

The other, perhaps, equally prominent reason, is that the residents of Dera Baba Nanak are eager for better relations between the two Punjabs—and the two countries—on either side of the border. History records that Guru Nanak spent years at this kasba, while he was a cultivator in nearby Kartarpur. The residents believe that Nanak drank from the same well that they draw water from today.

The residents of Dera Baba Nanak long for the return of a sliver of that past in which the Punjabi people as a whole revered Guru Nanak, regardless of religion. They are praying that in the opening of this new route or “corridor” to Kartarpur, their filial, religious, emotional and economic ties with Pakistan and its Punjabi citizens will improve.

“November 9 is a fortunate day for me. On this day, with the blessings of my guru, I will be at Gurdwara Kartarpur Sahib and kiss the earth of my Punjab, whose rulers have kept us Punjabis apart for 72 years,” says Swaroop Singh, a Dera Baba Nanak resident.

Gurmukh Singh, another faithful at the small gurudwara in the kasba says, “Punjabis of both countries have been longing to embrace each other, but Indian and Pakistani governments have kept us apart. Now Guru Nanak patshah is pleased. When this corridor opens, relations between the two countries will also improve.”

Without a doubt, despite the recent extended bout of ill-will between India and Pakistan, the hearts of India’s and Pakistan’s Punjabis are beating for each other. On November 9, the prime ministers of both countries, India’s Narendra Modi and Pakistan’s Imran Khan, will inaugurate the Kartarpur corridor. To Dera Baba Nanak residents, this will be no less than a new phase in the history of Punjabis. They hope that through this effort, not just mutual trade but even relations between the two countries will improve.

The Punjabi language, the shared music and literature and their mutual warmth deepens the relationship between Punjabis in India and Pakistan. Being a border state, Indian Punjab is also badly affected whenever India and Pakistan engage in tussles or warmongering, if not war.

The people of this border region have been uprooted again and again, and yet in Punjab there is no hatred towards Pakistan. Over the past five or six years, every time tensions with Pakistan escalated, Punjab did not join the chorus against Pakistan. When voices clamoured to “teach Pakistan a lesson”, Punjabis decried the very idea of war and the loss and destruction it brings in its wake. (There were heavy losses of life and property during the 1965 and 1971 wars and the 1999 Kargil war.)

Punjabi youth shared anti-war poems, stories and films on social media every time war cries were raised in other parts of the country. As an elderly man from the border area says rather emotionally, “It is easy to sit in Delhi and talk about war, but ask people like us, who live along the border: who are we to throw our ammunition at our Punjabi brothers and sisters.”

Even now, just before the launch, when the government of Pakistan released the song Pavitra Dharti Nanak Di [Holy Earth Nanak Walked on], dedicated to the Kartarpur corridor, it is being appreciated in both Punjabs.

Punjabis revere Indian and Pakistani leaders who initiate friendship between the two nations. It is no surprise that they are feting Navjot Sidhu and Imran Khan today. Nirmal Singh, general secretary of Punjabi Sathth Lambda, an organisation working for Indo-Pak friendship, says, “Many are lauding Sidhu [minister in Punjab government], but rightfully the credit goes to the Punjabis on both sides, who forced their governments to create it.” He says that to Punjabis the Kartarpur corridor is not restricted to a matter of religious faith. “They are viewing it as a beautiful new chapter in the relationship of both Punjabs,” he says.

Noted Punjab-based journalist Hamir Singh, news coordinator of the prominent Punjabi Tribune newspaper, has kept a close watch on Indo-Pak relations. “A long-standing prayer of Sikhs has been fulfilled by opening this corridor. Sikhs were separated from their holy sites and will get a chance to go on this pilgrimage now,” he says.

Relations between India and Pakistan have stagnated for a while now, intermittently exploding in tensions, marked by skirmishes and, lately, military strikes. But the Kartarpur corridor faced almost no obstruction. “After a long time, the authorities of India and Pakistan forged an amicable settlement,” says Hamir.

The roots of Punjabiyat are very deep, despite strained relations on the long border with Pakistan. “Literary and cultural exchanges have continued between the two Punjabs through it all,” says Satnam Singh Manak, general secretary of Hind-Pak Dosti Manch. “Both Punjabs bow their heads before Nanak, Bulla, Farid and Waris Shah. And the singers Nur Jahan, Prakash Kaur and Surinder Kaur beat in the hearts of every Punjabi. In such a context, the Kartarpur corridor will become a bridge between people,” he says.

Responses in Pakistan Punjab

Pakistan Punjab is equally enthusiastic: poet Afzal Sahir says he does not like to distinguish between Indian and Pakistani Punjabis. “Punjab is Punjab,” he says. “If Guru Nanak is the guru of Hindus and Sikhs, he is also the pir of Muslims,” he says. “Today, Baba Nanak is again becoming a means to connect his Punjab.”

In 2013, Nasir Dhillon, a Pakistan Punjabi, started a YouTube channel, Punjabi Lehar, to connect both Punjabis. “Like the Punjabis of chadhda Punjab [rising Punjab, another YouTube channel] we, too, eagerly await November 9. So long after Partition, the younger generations are still haunted by its wounds. On that day we will get to meet our brothers from whom we have been separated for long; I wish that day never ends...”

The Pakistani government hopes that the economic brotherhood will also increase with the increase of religious excursions between the two countries. Several significant Sikh sites of worship are located in Pakistan, mainly in Lahore, Nankana Sahib, Hasan Abdal and Kartarpur Sahib. After the Partition, the Sikh population in Pakistan fell to just about 70,000. Besides, Pakistan is in an interesting situation with respect to holy sites: An Islamic country, most of its holy sites are in Saudi Arabia, Iraq or Iran. Thus, to develop religious tourism, Pakistan’s first preference would have to be places related to Sikhism. Just like India developed places important to the Buddhists in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, although a minuscule percentage of Indians are Buddhists. A similar opportunity to attract tourists from overseas is now before Pakistan.

Economic relations between India and Pakistan have been deteriorating for some years, but traders of both countries are keen on good business relations too. For them, this corridor is a positive signal. The well-known journalist Sanjeev Pandey says that the problems in the neighbourhood have adversely affected agriculture and industry in Pakistan. “During the last twenty years, Pakistan’s economy has lost $125 billion due to terrorism. Because of this, Pakistan’s democratic government and military have both faced crisis after crisis.”

In the same way, traders from Amritsar and Lahore have high hopes from the opening of the corridor. Experts say that all of north India will benefit by increasing trade with Pakistan through Punjab. There is also a demand from the Lahore Chamber of Commerce and Industry to increase trade with India through the Punjab border. The leaders of Indian Punjab have also continuously emphasised on the need to improve economic relations through this region.

Right now, only the Attari border near Amritsar is open to economic exchanges between India and Pakistan. Economy experts say that the potential for mutual trade is close to $30 billion while the current mutual trade is barely $2.50 billion. And Pakistani economists believe that if the Kartarpur corridor ends up improving relations between people, it will directly benefit many industrial areas in Pakistan.

For instance, Pakistan’s automobile industry will be able to import essential goods from Gurgaon and Manesar in India. Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry will also benefit immensely too. Farming cooperation between the two countries is also expected to increase.

Work on the Corridor on the Pakistan Side

Pakistan claims that around 5,000 compatible Sangat Gurudwaras will be able to visit Kartarpur Sahib everyday through the corridor. Government of Pakistan spokesperson Muhammad Faizal, who signed off on the corridor arrangement, says that an environment of cross-border tension makes thrashing out a compromise tough. According to him, Pakistan planned to impose a $20 service charge on visitors to the corridor to recoup a quarter of expenses it undertook to build it. [Khan waived this fee a few days ago.]

Three rounds of negotiations—two at Attari, one at Wagah—took place to make the corridor acceptable to all. Khan has candidly acknowledged that Pakistan is going through an economic crisis, but he has said there will be no skimping on the corridor. “It will increase trade and tourism,” says Faizal.

Atif Mazid, Pakistan project director of the Kartarpur corridor, who is also responsible for the care of visiting pilgrims, the gurudwara building and the residences coming up around it, says that the entire project was executed with the wishes of the Sikh brotherhood in mind. “It was a big challenge but with the blessings of Baba Nanak, we have succeeded. Now Kartarpur Sahib is the largest gurdwara in the world.”

Previously, the gurudwara was to be situated on a four-acre plot with plenty of forested land surrounding it. Now 43 acres of marble have been planted in and around it. The 26 acres of land near the Gurudwara, on which Guru Nanak Dev had lived and worked as a cultivator, have been kept intact and are still reserved for farming. Another 36 acres have been kept for a garden and sundry other project. The Indian side of the gurudwara building has been kept open—to give devotees coming from India an unrestricted view of it from Dera Baba Nanak itself.

A big langar (dining) hall has been built to seat 2,500 devotees at a time. There are libraries, museums and residential rooms. In all, 404 acres of land have been acquired so far. Pakistan has plans to develop 800 acres as part of the project.

While people in Indian Punjab have not objected to the $20 dollar fee imposed by Pakistan, the leaders of Punjab are questioning this. Ordinary people say that if their leaders are so anxious about the devotees’ expenses, then the Punjab and central governments should compensate for it. As Gurmeet Singh, a devotee, says, “It can cost Rs 1 lakh to get a booking at a prominent Delhi gurdwara. First Sikh leaders should stop corruption their institutions. Second, devotees to Harmandir Sahib [Golden Temple] pay hundreds of rupees as toll tax while getting there. Will the government waive this fee?”

The Sikh devotees of Punjab are also worried about different celebrations various political parties are organising to mark the anniversary of Guru Nanak’s birth this year. But they all know, it is competitive politics, and haven’t they resisted that for so long anyway?

Shiv Inder Singh is an independent journalist. The views are personal.

This is a translated and edited version of a column published in Hindi.Newsclick.in

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.