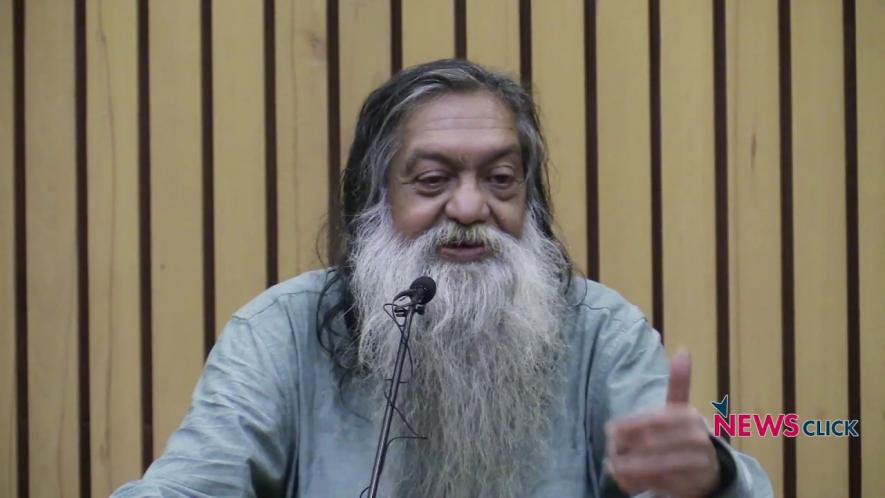

Abhijit Sen: Pro-People Economist who Always Thought About the Poor

Professor Abhijit Sen was our teacher at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning (CESP), Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. After completing PhD from the Cambridge University, he joined JNU in 1985 and taught there on a wide range of subjects like agriculture, planning, labour economics, microeconomics, macroeconomics, growth economics, statistics at postgraduate and MPhil/PhD levels for more than 30 years.

As a teacher and class lecturer at one of the best centres of economics in the country, Sen was one of the best at CESP and hugely popular among students because of his extremely sweet and approachable nature.

As a committed policymaker, Sen was the chairperson of the Commission for Agricultural Costs & Prices (CACP) and a member of the Planning Commission for 10 years and the 14th Finance Commission. He was also a member of the State Planning Boards of West Bengal and Tripura.

The eminent economist’s main areas of research were agriculture, rural development, unemployment, wages, food security, poverty, inequality and decentralisation in India. He was a pro-people leftist economist who always thought about the poor, the marginalised and the downtrodden. He was definitely one of the brightest minds with a golden heart.

As the chairperson of CACP, Sen recommended the inclusion of various indirect costs of production in agriculture like unpaid family labour, opportunity costs from rent and interest lost on owned land and the capital asset costs while computing the minimum support prices (MSP) for crops. As a result, the state-wise cost calculation and the associated MSP of different crops could increase by almost 50%, which was reflected in the ‘Swaminathan formula’ later.

Simultaneously, Sen also advocated for wider coverage under the National Food Security Bill way above the official poverty line and supported universal Public Distribution System (PDS) over targeted PDS, which only covers Below Poverty Line families.

Sen knew the National Sample Survey (NSS) data better than anybody else. In the great Indian poverty debate, he supported the official national poverty line based on the Tendulkar Committee recommendations (to make it comparable with the previous estimates). At the same time, as a policymaker, he realised the need of increasing the coverage of food grain distribution at subsidised prices through the PDS—as the official poverty line, given the estimation methodology, was extremely low.

Obviously, if the coverage and the offtake of food grains rise in the PDS, the procurement through MSP and its coverage also have to go up. If farmers get a better price for their produce because of higher MSP, which sets the floor of prices, there would be some money flow towards the agricultural sector and the rural economy. The food subsidy bill of the government may increase. However, Sen thought that this was far more important than the ongoing fiscal conservatism.

During the formulation of 11th and 12th Plan documents with the vision of ‘inclusive growth’, Sen was always extremely serious about the distributional aspects in general. The mainstream growth model in the policymaking circle was primarily of profit-led growth. However, he was continuously raising the questions of unemployment, low wages, poverty and rising inequality.

When public private partnership, special economic zones (SEZs) and facilitating big investors in different ways were being discussed to ensure higher growth rate, Sen was in favour of greater money flow towards informal-unorganised sectors of the economy, rural agriculture and petty production and social sectors for human development.

Sen was definitely not opposed to growth but he probably had an idea of wage-led growth in mind by improving the multipliers through ensuring better distribution of national income by changing the composition of the public spending in favour of the poor. Same amount of government expenditure or investment or export would be more effective in generating more employment and ensuring higher growth under a demand constrained situation at the aggregate level if the consumption propensity rises in the economy.

Since, the propensity to consume is higher for the poorer section, a redistribution of real national income from the rich to the poor can ensure higher growth. Sen was of the opinion that the expansionary monetary policy would not be inflationary in the Indian context because of the presence of a huge informal and unorganised sector.

By undertaking the expansionary demand management policies and also changing the composition of the government expenditure in favour of the poorer section, high growth can be ensured along with reduced unemployment, poverty and inequality.

Sen was a strong supporter of expanding government expenditure in health and education and for employment generation and poverty alleviation. Inside the Planning Commission, he was the main voice for bargaining in favour of the interest of the poor and the common people—for making the growth process inclusive in true sense.

The success of various centrally sponsored flagship schemes, including the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), Mid-Day Meal Scheme (MDMS), PDS, Prime Minister Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY), etc. have ensured some human development for sure.

Sen was also a strong voice in favour of fiscal federalism and decentralisation. The 14th Finance Commission (chaired by professor YV Reddy) recommended an exceptionally high increase in the states’ share of the common pool of taxes from 32% to 42%. Still Sen was unsure about the amount of increase in the total transfer to the states in future as the grants and other transfers (apart from the tax devolution) might have reduced as a proportion of the GDP.

To the best of my understanding, Sen believed that most of the human development-related issues have to be dealt with at the regional and local levels and empowering the lower tiers of the governments is absolutely essential in that direction. He would try to convince people who had a different opinion with the help of concrete empirical evidence and pure logic. His objective analyses and reading of data were next to impossible to dismiss—his academic arguments earned enormous respect across the board.

At the same time, common people, including labourers, farmers, especially the poor, never got lost in the technicalities of sophisticated economic modelling. Sen’s sharp interventions in policymaking circles helped the common people to bargain strongly under the extreme neoliberal environment.

Sen always tried to ensure ‘constrained-optimisation’ for the interest of the common people and the poor inside the highest-level of policymaking. Obviously, there were successes and failures. However, he was always peoples’ economist in true sense.

The writer is assistant professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.