The Migrant as Citizen

We are witness to the most horrific tragedy in our country’s history. The most visible part of the tragedy is the movement of the inter-state migrants back to their homes. It is estimated that one of the consequences of this lockdown has been an estimated 114 million job losses (91 million daily wage earners and 17 million salary earners who have been laid off), across 2,71,000 factories and in the 65 to 70 million small and micro enterprises that have come to a halt.

Who is a migrant worker? Why is he/she treated as an outsider instead of as a citizen of his/her country with full rights guaranteed under the Constitution, the law and international labour standards?

There is a need to intervene in the situation to ensure that the migrants are guaranteed that their right to livelihood is ensured both in their original home state, and at the place where they migrate. International agencies have been developing the concept of safe migration – we need to look at the concept more closely in our own context:

1. The Migrant and Migration

There is no reliable data on the number of Indian migrants working abroad, or within the country. However, even with the limited data, statistics show the scale of the issue.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), India is a major country of origin and transit, as well as a popular destination for workers across international borders. As per official figures, there are over 30 million Indians overseas, with over 9 million of the Indian diaspora concentrated in the GCC region (now known as the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf). Over 90% of Indian migrant workers, most of whom are low and semi-skilled workers, work in the Gulf region and in South East Asia. An analysis of international migration trends in India is inhibited by the limited official data available. Data is available only for workers migrating on Emigration Check Required (ECR) passports, to one of the 18 ECR countries.

The International Organization of Migrants (IOM) estimates that there are 271.6 million migrants all over the world, as of 2019. Established in 1951, IOM is the leading inter-governmental organization in the field of migration, and works closely with governmental, intergovernmental and non-governmental partners.

According to the IOM, the word “migrant” is “an umbrella term, not defined under international law, reflecting the common lay understanding of a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons. The term includes a number of well-defined legal categories of people, such as migrant workers; persons whose particular types of movements are legally-defined, such as smuggled migrants; as well as those whose status or means of movement are not specifically defined under international law, such as international students.”

It is to be noted that at the international level, no universally accepted definition for “migrant” exists.

2. Who is a Migrant Worker in India?

The Census defines a migrant as a person who “is enumerated in census at a different place than his / her place of birth, she / he is considered a migrant.”

Millions of men and women migrate from their homes in rural India to towns and cities, in search of work, especially during certain seasons. It is estimated that 120 million people or more migrate from rural areas to urban labour markets, industries and farms.

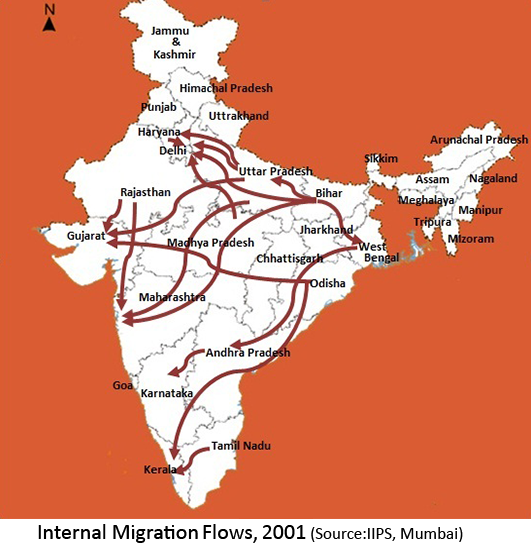

The major migration corridors in India along which large-scale movement of workers takes place, are shown in the map below. Some regions like UP and Bihar have been known for rural migration for decades; however, newer corridors like Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and recently even the North-East, have become major regions where people engaging in manual labour come from.

Among the biggest employers of migrant workers is the construction sector (40 million), domestic work (20 million), textile (11 million), brick kiln work (10 million), transportation, mines and quarries and agriculture. The internal migration almost doubled over 20 years — from 220 million in 1991 to 454 million in 2011.

In addition, according to the Census 2011, around 5.5 million people in India had reported their last residence as having been outside the country, which is roughly 0.44 per cent of its total population. Of these, 2.3 million (42%) came from Bangladesh and 0.7 million (12.7%) from Pakistan. The number of immigrants from Afghanistan was low, at 6,596.

These numbers show that roughly 55% of the immigrant population who recorded their last residence outside India, belonged to Pakistan and Bangladesh alone. The Census data gives details about the time period for which these immigrants have been staying in India, thus helping us decipher when they arrived here. The major immigrant flows have been recorded during and after Partition and the 1971 Bangladesh liberation war.

3. Legal and Constitutional Protection of Migrant Workers

It may seem a little redundant to speak of the legal protection of migrant workers in the context of the mass exodus of migrant workers during the pandemic, but it is precisely why we need to know the laws that are in place, and ask why despite these, the migrants had no way of enforcing their legal and constitutional rights.

Since its inception, the ILO has adopted 181 legally binding conventions and 188 recommendations aimed at improving labour standards across the globe. There are eight core labour standards. There are four categories such as: i) Right to freedom of association and collective bargaining ii) Elimination of forced labour iii) Elimination of child labour iv) Elimination of discrimination in matter of occupation and wages.

Under the Indian Constitution, the migrant worker, who is a citizen of India, has certain fundamental rights under Part III of the Constitution of India.

In addition, there are labour laws which protect all workers – such as the Minimum Wages Act, 1948 and there are labour courts, labour commissioners and a system in place for the legal protection of all workers.

In addition, the Inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Condition of Service) Act, 1979, was put in place more than 40 years ago.

A report by the UNICEF in 2012 noted that the Act needs to be revised:

“Revise the Inter-State Migrant Workmen(Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act (1979) including the following gaps:

– The Act applies to only migrants crossing state boundaries and, therefore, a large section of migrants are excluded from its ambit.

– It does not monitor unregistered contractors and establishments.

– It remains silent on provision for crèches, education centres for children or mobile medical units for the labourers.

– It articulates no guidelines for inter-state cooperation.

– It covers only regulation of employment and conditions of service of migrants and does not address access to social protection of migrants, their right to the city and the special vulnerabilities of children and women migrants.

– Important provisions of the Act such as minimum wages, displacement allowance, medical facilities and protective clothing remain unenforced.”

4. Migrant Worker as Outsider

Why is the migrant worker not able to enforce their rights? This question is valid for all poor people, because the legal system is balanced in favour of the rich and powerful. However, migrant workers are the most vulnerable in the citizenship hierarchy.

The migrant worker has been a target of identity movements which have been rising in every part of the country. They are looked upon as “outsiders” and made a scapegoat for all the social and economic problems facing people; mostly unemployment. In erstwhile Bombay (now Mumbai), the Shiv Sena has targeted migrant workers several times; in North-East States the migrant worker is a target of physical attacks and migrant workers have been assaulted in Kashmir.

In contrast, the Kerala government has organised 15,541 relief camps for migrant workers, the highest in any State.

Even where the migrant worker is treated with dignity, as in Kerala, they are called guest workers and are dealt with by the Department of Non-Resident Keralite Affairs (NORKA).

So, the question arises: Is a migrant worker not a full citizen if he or she goes to another state within the country? Are they to be looked upon as outsiders in their own country?

The first ever task force on migration, the Working Group on Migration, formed by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation and headed by Partha Mukhopadhyay from the Centre for Policy Research, was set up at the end of 2015. In its report, the panel stated that the migrant population contributed substantially to economic growth and that it was necessary to secure their constitutional rights. The 18-member working group submitted its report in January 2017.

The report began by stating that in principle, there was no reason for specific protection legislation for migrant workers, inter-state or otherwise, and that they should be integrated with all workers as part of a legislative approach with basic guarantees on wage and work conditions for all workers, as part of an overarching framework that covers regular and contractual work.

5. Migrant Worker and Indian Federalism

The primary responsibility for the welfare of the migrants lies with the Government; as it does for all citizens. However, the Centre announced the lockdown without notice, and as a result, the migrants became jobless overnight, and found themselves without food or shelter. Then the Central Government tried to shift the burden of transporting the migrants on to the state governments; and there were conflicts between the host state government and the states in which the migrants were working.

The pandemic has brought out the fissures in the Indian federalism. In the fight between the Centre and the states, it was the migrant worker who was the centre of the crisis of the Indian Constitution, and a vulnerable victim.

The inter-state migrant worker was denied their wages by contractors and employers; thrown out of rented rooms by landlords despite a notification by the Central Government and a Supreme Court order later; denied alternate shelter or food by the local administration. In a large part this was possible because the employer/contractor and the landlord were “locals”, and the migrant workers were the “outsiders”.

Even volunteers who helped with the distribution of food focused on getting the migrant worker back to his place of origin, rather than helping them get wages and shelter. And then there were cases in which a contractor or employer refused to let the migrant return, because they needed cheap labour. However, the migrant worker had no way to fight back, because trade unions failed to take up the rights of migrant workers – many times because the organised workers are often “local”; and the MPs and MLAs did not help the migrant worker because they are not voters.

The 2019 Lok Sabha Elections had a 67.11% turnout — approximately 60 crore of the 90 crore eligible citizens voted. Of the more than 30 crore voters who were not able to vote, migrant workers constituted a major proportion.

The migrant worker is a disenfranchised citizen who has no way of enforcing their rights.

6. Contribution of Migrant Workers to Domestic Economy

Although we know that migrant workers form the backbone of the Indian economy, there are no reliable figures on their contribution to it. Priya Deshingkar is a professor of migration and development, and along with a colleague, has collated a number of empirical studies which indicated that the major sub-sectors using migrant labour are textiles, construction, stone quarries and mines, brick-kilns, small-scale industry (diamond cutting, leather accessories, etc.), crop transplanting, sugarcane cutting, rickshaw-pulling, fish and prawn processing, salt panning, domestic work, security services, sex work, small hotels and roadside restaurants/tea shops and street vending. Their calculations based on these estimates indicated that the economic contribution of migrants was around 10% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP).

In a later study, they showed that internal remittances in India totalled $7.485 Billion in 2007-08 – highlighting the poverty and inequality reducing potential of internal migration, as the money flows directly to families in poorer parts of the country.

According to the International Labour Organization, there are between 20 and 90 million domestic workers in India, and many of them are migrants. Women’s work is often unrecognised, and even more so if one is a migrant (another reason for the underestimation of women’s circular migration is the failure to go beyond the primary reason for movement, which is marriage, and recognize that many work after marriage).

There is an urgent need to make the contribution of migrant workers visible.

7. Controversy over Illegal Migrants

The core of the controversy over the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, is to do with illegal migrants. Ever since the anti-foreigner movement in Assam (1979-1985) the issue of detection, detention and deportation of illegal migrants has been on the agenda of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

There has been a campaign to vilify the illegal migrant as a terrorist and a threat to national security. By the year 2000, the Muslim illegal migrant was being called an infiltrator and there was a fear psychosis created that there are millions of Bangladeshi illegal migrants who pose a threat to India’s national security. The threat was articulated mostly in Assam.

Then, in 2003, the Citizenship Act was amended to make it virtually impossible for even children of illegal migrants born in India to acquire citizenship by naturalisation.

In other words, even if a person was born in India but one parent was an “illegal immigrant”. the person would be liable to be deported.

The demand for weeding out the illegal migrants was most vociferous in Assam and in the North-East, especially after the influx of refugees during the Bangladesh liberation war. The task of detection of illegal migrants proved far more complex than anticipated. Finally, the task was undertaken under the supervision of the Supreme Court, and between 2013 to 2019.

The final National Register for Citizens for Assam, published on August 31, 2019, contained 31 million names out of the 33 million population. It left out about 1.9 million applicants, of whom 0.5 million were Bengali Hindus, 0.7 million were Muslims and the rest appear to be local people and Hindus from north India.

The result was that 19,06,657 persons, who were not included in the final register, were registered as “doubtful citizens”. The only remedy for those who had been registered as doubtful citizens was to go before the Foreigners Tribunal with an appeal against non-inclusion. Among those excluded were the family members of the former President of India, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed (1974-77), and Kargil war veteran Mohammed Sanaullah, who was jailed for his failure to establish himself as a citizen.

Many families were torn apart when one member was put in the doubtful category and detained.

With the passing of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) in December 2019, those non-Muslims who have been declared “doubtful citizens” can claim to be illegal migrants and get Indian citizenship by a liberal procedure. This trend has caused the international community to express their concerns. For instance, George Soros, the billionaire philanthropist said the following in the Davos meet in January 2020:

“Nationalism, far from being reversed, made further headway. The biggest and most frightening setback has come from India where a democratically elected Narendra Modi is creating a Hindu nationalist state, imposing punitive measures on Kashmir, a semi-autonomous region and threatening to deprive millions of Muslims of their citizenship.”

In contrast, the Muslim doubtful citizen would have to produce documents to prove he or she is an Indian citizen, or else be liable to be detained indefinitely as an illegal migrant without hope of getting Indian citizenship for themselves or their children.

In other words, the Muslim illegal migrants could become stateless, without protection.

The indigenous communities living in the North-East states do not want any illegal migrants, Hindu or Muslims getting citizenship rights, because they are being out numbered and there is a threat to their identity. The CAA gives some protection to this part of the country from an influx of migrants. Assam, Tripura and Meghalaya (with borders with Bangladesh) continue to demand for National Registers for Citizens in their states.

However, the Muslims living in the North-East are apprehensive that they would be disenfranchised by a National Register of Citizenship, which requires documents they do not have.

8. Documentation of Migrants in India

Many migrant workers do not have identity proofs or any documents which would allow them to access social welfare schemes made in their name. The possession of a specific document linked to accessing a scheme has also resulted in gross violations of workers rights.

There is obviously a need to document the number of migrant workers, legal or illegal, for the purpose of extending social welfare schemes and legal protection to them.

In March 2019, as many as 108 economists and social scientists called for the restoration of "institutional independence" and the integrity of statistical organisations.

The 108 experts from across the globe, further said that in fact, any statistics that cast an iota of doubt on the achievement of the government seem to get revised or suppressed on the basis of some questionable methodology.

“This is the time for all professional economists, statisticians, independent researchers in policy regardless of their political and ideological leanings to come together to raise their voice against the tendency to suppress uncomfortable data...”

9. Who is Responsible for Relief and Protection of Migrant Labourers?

The enormous mobilization of funds in the name of the migrants is commendable. The corporates, organisations and individuals donated generously. Restaurant owners associations distributed 50,000 meals in the first month.

While it is commendable that many individuals and NGOs provided food and shelter to the migrants during their exodus, the question that remains is what happened to the crores that was mobilised in their name by the Prime Minister and the Chief Ministers?

The Prime Minister National Relief Fund (PMNRF) has been around since 1948 and in March, 2020, the Prime Minister established the PM CARES Fund; the Minister of Defence, Minister of Home Affairs and Minister of Finance, Government of India, are ex-officio trustees of the fund.

PM CARES Fund has got exemption under the FCRA, and a separate account for receiving foreign donations has been opened. This enables PM CARES Fund to accept donations and contributions from individuals and organizations based in foreign countries. The objectives of the fund are:

1. To undertake and support relief or assistance of any kind relating to a public health emergency;

2. To render financial assistance, provide grants of payments of money or take such other steps as may be deemed necessary by the Board of Trustees to the affected population; and

3. To undertake any other activity, which is not inconsistent with the above objects?

The question is: Where did these funds go? How much actually reached the migrant worker? The PM Cares Fund is not a public authority and so does not come under the RTI.

Migrant workers were not given wages, nor were they given food in the shelters or during their journey back home; they often they paid for their own transportation.

It is important formcivil society to find ways and means to get the Government to be accountable and transparent; especially since government servants and even army personnel have had their salaries cut and been compelled to donate to the cause of the migrants – they have a right to know how their money has been spent.

However, it is also necessary to make corporates accountable, because often their donations have been been in lieu of their corporate social responsibility and not in addition to it. Donations to the cause of migrants cannot be in place of existing CSR commitments.

10. Challenges Ahead

In a bid to revive the economy, the Centre has announced an economic package; it has also announced ordinances by which it intends to “reform” labour laws. According to manufacturers and industrialists, a major obstacle in the way of development is the “over protection of workers”.

The Yogi Adityanath-led government in Uttar Pradesh has made defunct all labour laws, including the Minimum Wages Act. The laws that have been relaxed include those relating to settling industrial disputes, occupational safety, health and working conditions of workers and those pertaining to trade unions, contract workers and migrant labourers, for the next three years.

In Rajasthan, the government has increased the threshold for layoffs to 300 people, from the earlier 100. Moreover, the membership threshold for trade unions has been increased from 15% to 30%. Working hours have also been raised to 12 hours per day from the earlier eight. Other states, such as Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat have also increased working hours.

Trade unions will not have any legal sanctity and any agreements signed on behalf of the employees will no longer be binding. Labour departments will become defunct and labour officers will not have any authority anymore.

The laws and economic measures being undertaken in the name of a revival of the economy are actually being enforced to re-frame labour-capital relations and redefine the role and nature of state intervention. Therefore, anyone interested in intervening in favour of workers, migrant or organised, must understand the political implications of these fundamental changes, both in the domestic and international economy.

Central to the task of enforcing rights is the political understanding of the problem and building political organisations strong enough to withstand the repression that they will face in the process of enforcing rights.

Social media is not a substitute for political mobilisation, organisation and action. And political mobilisation must begin with the political understanding of the situation at the local, national and international levels.

The old adage that we need theory and practice has acquired an urgency because of the de-legitimisation of political institutions and organisations.

Here are some basic political questions that need to be addressed urgently:

1. How can the inter-state migrant worker be treated as a full citizen with all his/her rights under the Constitution of India and labour laws?

2. What should be the role of Central Government, State Government and citizens in addressing the problem of migrants?

3. What should be the rights of illegal migrants in a globalised world?

4. Is there a possibility of having special provisions for residents of specific parts of the country like Kashmir and the North-East where the locals feel a need for specific protection of their culture, religion or identity?

11. Safe Migration

While we debate and discuss the deeper issues, there is a need to take immediate steps for making migration safer in the future.

The idea of safe migration has come up in the context of the trafficking of people across international borders, and the concept helps to focus on aspects of migration other than repressive border control regimes; the idea is to focus on the rights of migrants regardless of migration status i.e. whether they are legal or illegal migrants.

Some states have set up monitoring cells for migrants and are in touch with the local embassy. The Indian Embassies have on occasion helped the migrants in dire straits and this role could be strengthened.

This concept of safe migration is relevant for addressing the problem of illegal migrants within India.

12. Safe Migration within the Country

Local self-government institutions can play an important role in a scheme for self-registration for migrants leaving their villages and migrating to towns.

However, there is also a need to ensure safe migration for inter-state migrants within India, for citizens of the country. The Working Group on Migration made the following recommendations in 2017:

(i) Social protection

States must (i) establish the Unorganised Workers Social Security Boards; (ii) institute simple and effective modes for workers to register, including self-registration processes, e.g. through mobile SMS; and (iii) ensure that the digitisation of registration records was leveraged to effectuate inter-State portability of protection and benefits.

(ii) Self-registration

Migrants should be provided with portable health care and basic social protection through a self-registration process de-linked from employment status. The level of benefits could be supplemented by the worker or State governments with additional payments.

(iii) Food security

One of the major benefits that migrants, especially short-term migrants or migrants who move without their household, lose, is access to the public distribution system (PDS). This is a major lacuna, given the rights conferred under the National Food Security Act 2013. The digitisation of beneficiary lists and/or in some instances their linkage with Aadhaar permits the two actions necessary for portability of PDS benefits, that is (a) the modification of the benefit to permit the de-linking of individuals from households and (b) the portability of the benefit across the fair price shop system (or alternative methods, if used).

(iv) Health

The rudiments of a portable architecture for the provision of healthcare are in place with the portability of RSBY (Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana) and ESI (Employees’ State Insurance). The focus can be on covering contract workers and even unorganised workers under ESI, and the proposed use of portability to provide the benefits under UWSSA (Unorganised Workers’ Social Security). However, there is still a large gap in implementation, the level of basic benefits and in the ability of the worker to improve these benefits with supplementary payments.

The working group also recommended that the Integrated Child Development Services–Anganwadi (ICDS-AW) and auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs)—be advised to expand their outreach to include migrant women and children in the scheme.

(v)Education

The working group also recommended that Ministry of Human Resource Development encourage States to include migrant children in the annual work plans of SSA (Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan), such as under the Education Guarantee and Alternative and Innovative Education schemes.

This could include the establishment of residential facilities as well as providing support to a caregiver chosen by the family, as currently practised in some States. In doing so, it is imperative to ensure adequate child protection, basic services, and caregiver-to-child ratios.

(vi)Skilling and employment

The working group recommended that migrants have unrestricted access to skill programmes in urban areas; in cases where there are domicile restrictions, these need to be removed. The various Ministries of the Government of India need to ensure that skill programmes funded by the Union Budget support do not have domicile restrictions.

(vii) Financial inclusion

The working group recommended that the Ministry of Communications re-examine the Department of Posts’ electronic money order product, benchmark it to private (informal) providers in terms of cost and time for the delivery so that it could be a competitive option for migrant remittance transfers.

13. Controlling and Monitoring Labour Contractors and Placement Agencies

So far, the courts, labour commissioners and some NGOs have been monitoring the contractors and placement agencies. This has to be done at the local level. But, with growing privatisation, the contractors are going to become more powerful.

The labour legislation has become watered down; the courts ineffective, and the trade union movement weakened. NGOs seldom confront the state and cannot be effective in limiting the power of the contractors, but they may be able to check the abuse of migrants by placement agencies, with the help of the police.

There is a need for a public awareness campaign which could be helpful in making people more sensitive to the rights of migrant workers.

14. Engaging with State Institutions

We need both legal and political imagination to engage with state institutions to enforce the rights of migrant workers, especially at a time when labour standards are being lowered.

There is a need to understand how the State works, and engage with the public institutions such as courts and commissions, to ensure the democratic space for enforcing migrant workers rights are kept open.

However, the courts and commissions are generally most effective when dealing with individual rights or a violation of the rights of small groups. They are not capable of dealing with the violation of the rights of millions of people.

14. Organising and Direct Action

The task of organising migrant workers who are on the move is very challenging for traditional trade unions, but it is a challenge which has to be met. Ultimately, it is the migrant workers themselves who have to organise themselves in order to fight for their life and livelihood; for their self respect and dignity.

There is always the danger that if such organisations do not come up, the migrant workers will be driven to enforcing their rights through violent crime.

15. From Disenfranchised Migrant to Citizen

Only if the migrant worker becomes politically relevant will they be able to get their voice heard. There must be a way to allow them to vote, either in their home state or at their place of work.

In the battle for more accountability and transparency, the role of courts and independent commissions such as the National Commission for Women and the National Human Rights Commission of India can play a pivotal role.

There is a need to formulate a charter of demands addressed to the Central Government; another to state governments; to the NGOs and to trade union movements. There is also a need to engage with political parties by demanding that they make their stand on migrant workers known and that it becomes a part of their election manifesto.

It is then that the migrant worker will be able to claim their rights as a citizen.

The writer is a human rights lawyer and author.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.